CRACKING

THE EGYPTIAN

CODE

CODE

THE REVOLUTIONARY LIFE OF

JEAN-FRANOIS CHAMPOLLION

Andrew Robinson

Andrew Robinson

is the author of some twenty-five books. They include The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms, and Lost Languages: The Enigma of the Worlds Undeciphered Scripts, as well as a biography of Michael Ventris (The Man Who Deciphered Linear B). A former literary editor of The Times Higher Education Supplement, he is a regular book reviewer for newspapers, magazines and journals.

Other titles by Andrew Robinson published by Thames & Hudson include:

Lost Languages: The Enigma of the Worlds Undeciphered Scripts

The Man Who Deciphered Linear B: The Story of Michael Ventris

The Scientists: An Epic of Discovery

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Complete Beginners:

The Revolutionary New Approach to Reading the Monuments

The Story of Decipherment: From Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script

Breaking the Maya Code

See our websites

http://www.thamesandhudson.com

http://www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For my wife Dipli,

moromere

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jean-Franois Champollion has intrigued me for over two decades, as I wrote books on ancient and modern scripts, on archaeological decipherment, on genius, and on two remarkable individuals. The first of these was Michael Ventris the 20th-century decipherer of Minoan Linear B, Europes earliest readable script. Ventris not only admired Champollion: he too became obsessed with an undeciphered writing system as a schoolboy. The second figure was the scientist Thomas Young, a polymath who was Champollions leading rival in the decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Many scholars helped me generously in my research for those books. With this biography of Champollion, John Baines, professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, went to considerable trouble to locate an inaccessible publication about Champollion and to answer various queries. John Ray, professor of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, has, over the years and through his writings, been a source of stimulating ideas. The London Library proved invaluable for its collection of 19th-century books by and about Champollion. The library of the Egypt Exploration Society was also useful. I should also like to thank Des McTernan, curator of early printed books in French at the British Library, for his sustained attempt to locate the librarys missing copy of Champollions rarest publication, printed in Grenoble in 1821. Sadly, he did not succeed in finding it thereby, perhaps, inadvertently fulfilling its authors desire to suppress this controversial work.

I am grateful to my long-time editor at Thames & Hudson, Colin Ridler, for sharing my enthusiasm for a book about Champollion. Its production was expertly overseen by Sam Wythe, Sally Nicholls, Alice Reid, Phil Cleaver and Rachel Heley.

PROLOGUE: EGYPTOMANIA

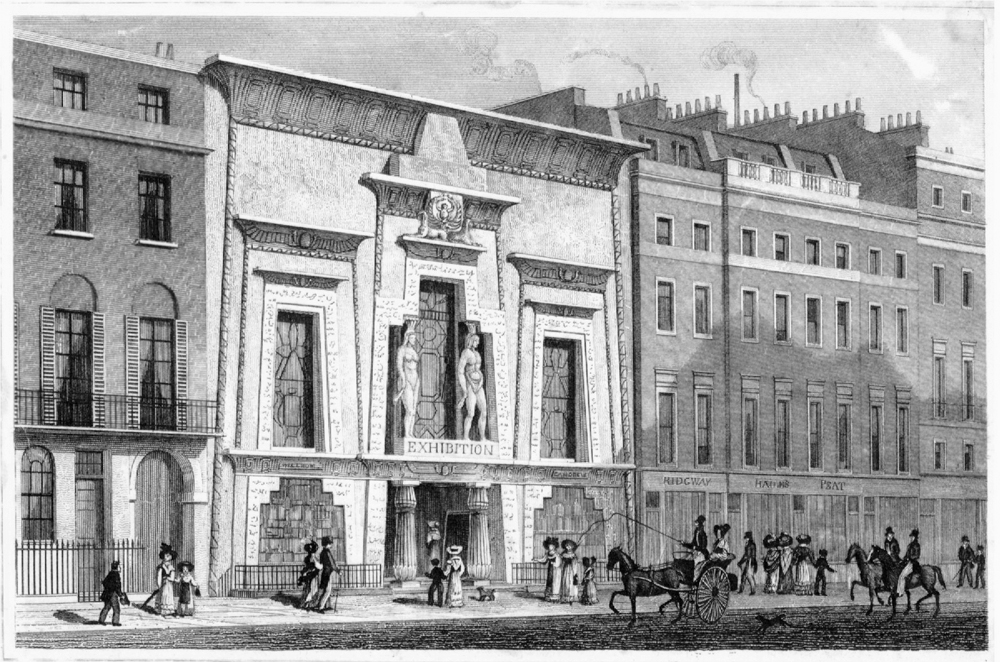

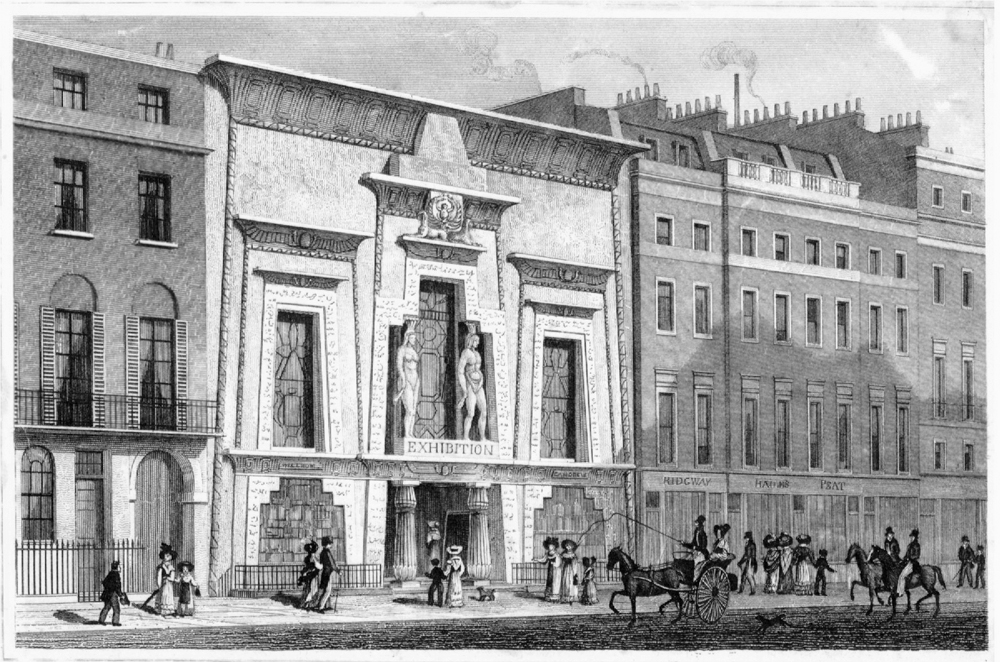

In 1821 a pioneering exhibition about ancient Egypt opened in Piccadilly, in the heart of fashionable London. Egyptomania, encouraged by Napoleon Bonapartes dramatic invasion of Egypt two decades earlier, was catching on in Britain as it had in Paris. The exhibitions venue, known as the Egyptian Hall, was a private museum of natural history. It had been built on Piccadilly in 1812, in an exotic Egyptian style, and featured an exterior decorated with Egyptian motifs, two statues of Isis and Osiris, and mysterious hieroglyphs. On display to the public, for the first time in Europe, was a magnificently carved and painted ancient Egyptian tomb, which had been discovered and opened three years earlier in the area of ancient Thebes (modern Luxor) that would later be known as the Valley of the Kings. At the inauguration ceremony, held on 1 May 1821, the tombs Italian discoverer, Giovanni Belzoni a former circus strongman turned flamboyant excavator of Egypt, who was about to become one of the most famous figures in London appeared wrapped in mummy bandages before a huge crowd. Some 2,000 visitors paid half a crown to see the tomb on the opening day; a reviewer in The Times newspaper called the exhibition a and skilful arrangement of objects so new and in themselves so striking.

Egyptian Hall, in Piccadilly, London, as seen in the 1820s. An early example of British Egyptomania, its facade was decorated with supposedly Egyptian statues and hieroglyphs.

(Print by A. McClatchy after T. H. Shepherd. Published in London, 1828. British Museum, London.)

Of course, what was on view was not the tomb itself, but rather a one-sixth scale model, which measured over 15 metres (50 feet) in length, complemented by a full-sized reproduction of two of the tombs most impressive chambers. The bas-reliefs and polychrome wall decoration, showing gods, goddesses, animals, the life of the pharaoh and manifold coloured hieroglyphs, had been re-created from wax moulds taken of the original reliefs, and from paintings made on the spot by Belzoni and his compatriot Alessandro Ricci, a physician turned artist. However, some of the objects on display were originals, such as two mummies and a piece of rope used by the last party of ancient Egyptians to enter the tomb. The pice de rsistance indeed, one of the finest Egyptian works of art ever discovered was an empty, lidless, white alabaster sarcophagus, almost 3 metres (10 feet) in length, which arrived by boat from Egypt in August, well after the exhibitions inauguration. Translucent when a lamp was placed inside it, with a full-length portrait of a goddess on the bottom, where the royal mummy would once have lain, the sarcophagus had sides carved, inside and out, with hieroglyphs, exquisitely inlaid with a greenish-blue compound made from copper sulphate.

When the exhibition closed, the sarcophagus was deposited in the British Museum. After the museums trustees prevaricated about purchase and eventually refused the object in 1824, it was sold for 2,000 to the architect Sir John Soane, who added it to the celebrated and curious art collection he kept in his private house not far from the British Museum. There, almost two centuries later, one can still see the sarcophagus as the centrepiece of the unique Egyptian crypt in the labyrinthine basement of what is now Sir John Soanes Museum.

To honour and publicize his new acquisition, and also to assist the widow of Belzoni (who had died in 1823), Soane arranged three separate evening receptions in 1825, specially illuminated by a manufacturer of stained glass and lighting appliances. A visiting artist, Benjamin Robert Haydon, described one of these social occasions in a vivid letter to a female friend that captures the London publics growing fascination with ancient Egypt:

beginning to meditate, the Duke of Sussex, with a star on his breast, and asthma inside it, came squeezing and wheezing along the narrow passage, driving all the women before him like a Blue-Beard, and putting his royal head into the coffin, added his wonder to the wonder of the rest.

Whose tomb was it that Belzoni had opened in 1817, and how old was the sarcophagus of its erstwhile occupant? No one had more than the vaguest idea, because no one could read the hieroglyphs. Accurate knowledge of hieroglyphic script had vanished since its last usage by Egyptian priests in the 4th century AD, a millennium and a half before Napoleons invasion.

Next page

CODE

CODE