CAMPAIGN 266

BAYONNE AND TOULOUSE 181314

Wellington invades France

| NICK LIPSCOMBE | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

| Series editor Marcus Cowper |

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN: THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE WAR

Beating from the wasted vines

Back to France her banded swarms,

Back to France with countless blows,

Till oer the hills her eagles flew

Beyond the Pyrenean pines,

Followd up in valley and glen

With blare of bugle, clamour of men,

Roll of cannon and clash of arms,

And England pouring on her foes.

Such a war had such a close.

Across the Pyrenees, Alfred Tennyson 180992

THE CONSEQUENCES OF VICTORY AT VITORIA

News of Wellingtons momentous victory at Vitoria on 21 June 1813 reached London in early July. Celebration spawned an expectation of a rapid conclusion to events in the Peninsula. His Majestys Government gave authority for Wellington to invade France and made noises and plans for the redeployment of the Peninsular Army in support of Russia and Prussia. Wellington, however, did not see things in quite the same way.

Major John Fremantle, Wellingtons ADC, took the Vitoria post-battle dispatch back to the Prince Regent in London. Francis Seymour Larpent, Wellingtons Judge Advocate General, recorded on 21 August 1813 that Major Freemantle came back just in time for dinner yesterday to amuse us with all your madness in England about the Battle of Vitoria. (By kind permission of Cdr C. Fremantle)

Wellington considered that a rapid curtain call to events in Iberia, followed by a swift pursuit of the Grande Arme across the Pyrenees and deep into southern France, an unlikely and unwise immediate course of action. His army, which had advanced over 600 miles in six weeks, often in contact with the enemy, then fought and gained a decisive victory, was exhausted. The troops, particularly those of his Portuguese and Spanish allies, were in a fearful state; many lacking basic equipment and all wanting for sufficient provision. By the end of June the remnants of King Josephs defeated armies had been driven across the French border; they were followed by Lieutenant-General Clausels relatively small but nevertheless significant Army of the North a week later. Still remaining in Spain were the French armies of Aragon and Catalonia, under the capable charge of Marshal Suchet. This combined force numbered in excess of 65,000 men and posed a serious threat to Wellingtons right flank. However, they were not the only French troops remaining on Spanish soil. Two large garrisons were holed-up at the great fortresses of San Sebastian and Pamplona; both had been resupplied and reinforced by the retreating French forces and both represented a serious threat to the Allied lines of communication. Furthermore, Wellingtons own lines of communication were now unwieldy and it had long been the plan, once northern Spain and the Cantabrian coast had been cleared, to move the British logistic base from Lisbon to Santander. This would be a time consuming operation and one which needed to be concluded before the invasion could commence.

Wellington was also acutely conscious of the political sensitivity surrounding the continued employment of Britains main expeditionary army in Iberia and the (hitherto unthinkable) invasion of French soil. The earlier fear that this small British expeditionary army would be destroyed had diminished. Prime Minister Spencer Perceval had been firmly of the view that retaining British soldiers in Iberia kept the Portuguese and Spanish fighting, causing problems in turn for France elsewhere in Europe. However, the boot was now on the other foot and, in the interim, Perceval had been assassinated and replaced by Lord Liverpool (the former Secretary for War) who had been decidedly non-committal on the issue. Furthermore, Napoleons Russian campaign had solicited charges, from her coalition partners, that Britain was not pulling her weight militarily.

The ruinous defeat of Napoleons Peninsular armies at Vitoria had changed all that. Beethoven composed his overture on the theme of Rule, Britannia! and even the Russians celebrated by singing a Te Deum in thanks and recognition. Moreover, the subsequent withdrawal of the remnants of those defeated armies, back across the Pyrenees, seemed to provide Lord Bathurst (the new Secretary for War) the rationale for Britain to throw our whole force as much as possible to co-operate with the Allies in the Netherlands. He later added, in correspondence to Wellington, we could move you, but not your army, a sentiment which solicited an understandably unenthusiastic response from the Allied commander-in-chief. The counterargument concluded that Wellingtons continued presence, coupled with an invasion of France, would be a serious obstacle to Napoleons attempts at the regeneration of his Grande Arme post-Russia, by tying down the remnants of his Spanish armies in defence of the southern border. Furthermore, Vitoria had changed the political landscape and subsequent outlook of, in particular, Austria who, having pontificated over an armistice extension with France, now threw in her lot with Russia and Prussia.

The scale of Wellingtons victory over the combined French armies at Vitoria was spoilt by a bungled pursuit. This was not entirely due to a thirst for plunder; far more credit should be given to the French cavalry for their actions following the collapse. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

WELLINGTONS PROBLEMS

Even before Napoleon had signed an extension of the armistice with the eastern powers, Wellington had reached the Pyrenees. Expectations that Wellington would maintain the momentum, invade France and bring the Iberian war to a swift conclusion were high. Reality was, in point of fact, very different. For although 2,000 prisoners and all the French artillery had been captured following the battle at Vitoria, more than 50,000 men had escaped via Pamplona and the Pyrenean passes to their homeland. Wellingtons problems were manifest and abundant. His battle-honed army had disintegrated in the immediate aftermath of victory. Wellington wrote to Lord Bathurst at the end of June that we started with the army in the highest order, and up to the day of the battle nothing could get on better; but that event has, as usual, totally annihilated all order and discipline.

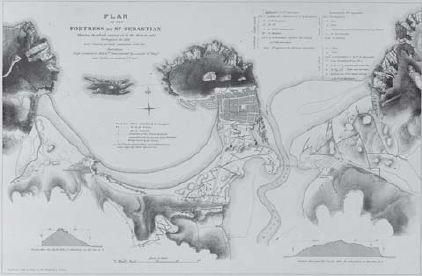

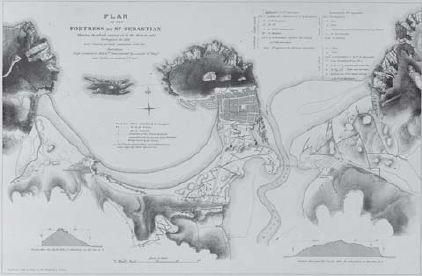

The town and castle of San Sebastian stands on a peninsula which projects north into the Bay of Biscay. Approaches are difficult and it was to prove a very difficult nut to crack. Foy reinforced the garrison with 2,500 men before he pulled back into France. (Authors Collection)

The event in question was the haul of treasure, the fruits of six years of plunder, reputedly the greatest ever captured by an army, which had been unavoidably, yet consequentially, strewn across the countryside by the fleeing French. It was undoubtedly a lost opportunity, prompting Wellington, tinged with indignant fury, to pen the often misinterpreted phrase that we have in the service the scum of the earth as common soldiers. His Allied troops too were in a dreadful state, lacking supplies, replacement uniforms, weapons and ammunition. The whole was subjected to living off the land; a logistic policy Wellington abhorred. Even the weather appeared to conspire against his men, as incessant and unseasonably heavy rain fell, prompting widespread sickness. At one stage practically a third of the Allied Army was