MY LIFE IS IN RUINS . Sorry, thats an old archaeologists joke. But odd bricks and stones, bits of broken pottery, rusty nails and shards of glassstuff anyone else would think was trashbring joy to my heart. This is why, on a chilly September morning in 2015, I found myself standing outside a tall plywood barrier in downtown Toronto, anxiously waiting to see what lay beyond. The Ontario government had commissioned a major excavation on the site of a new courthouse. Archaeologist Holly Martelle and her team were digging a full city block in what had been Torontos first immigrant-reception neighbourhood.

Beginning in the 1830s, Torontos old St. Johns Ward received wave after wave of newcomers from all over the world. But its first residents were refugees from bondage, people whose ancestors had been torn from Africa and carried across the Atlantic in the holds of stinking slave ships to build the New World. For thousands, the little houses and tenements lining those narrow streets were the last stop on the Underground Railroad.

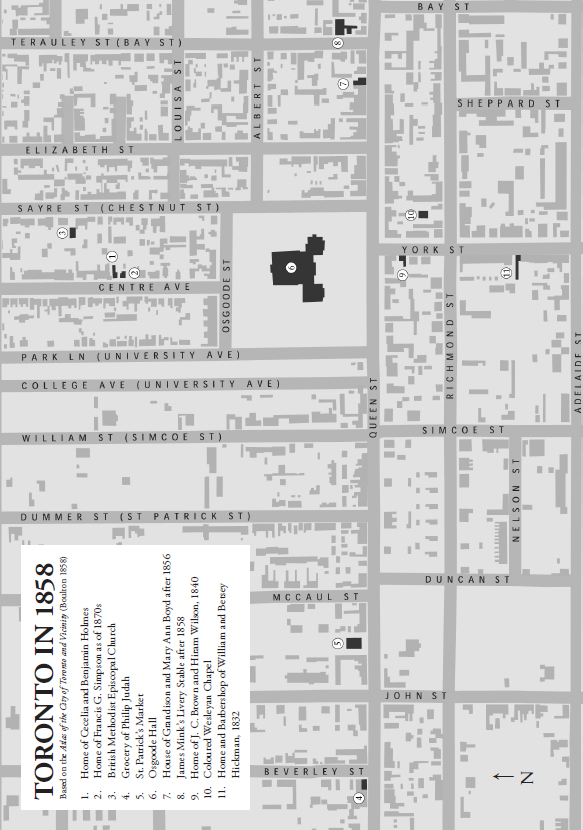

This densely packed city block had once been the beating heart of Black Toronto. Now soaring skyscrapers ringed the area of excavation. The makeshift gate to the site swung open. Inside lay an acre or more of dry soil covered with intersecting foundations of brick and concrete block two and three courses high, representing more than a century of building and rebuilding in this one limited space. A little to the north, in an area entirely cleared of debris, lay the foundations of the citys first British Methodist Episcopal church.

The archaeological discoveries were an unexpected gift. For the past ten years I had been piecing together clues to the life and times of one incredibly courageous fugitive slave woman named Cecelia Jane Reynolds. Now archaeologists were digging the foundations of Cecelias first home in freedom, laid bare again to the sky after decades of obscurity under an asphalt parking lot.

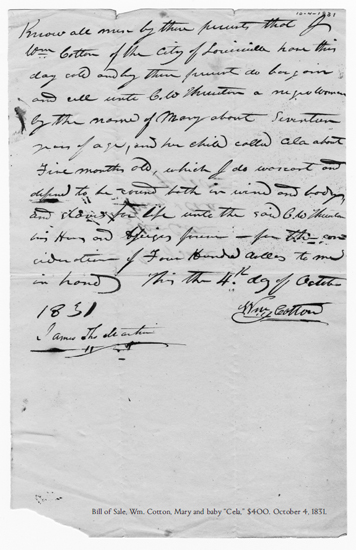

How fitting that the dig was taking place in such an uncompromisingly urban environment, evocative of the experiences of a woman whose life was lived out in cities. Most people, when they think about slavery at all, see in their minds eye enslaved men and women picking vast fields of cotton. But Cecelia was not a plantation slave. Indeed, hers was a quintessentially urban experience. Her home in slavery had been Louisville, Kentucky, a city that looked both to the North and South and shared some of the traits of each.

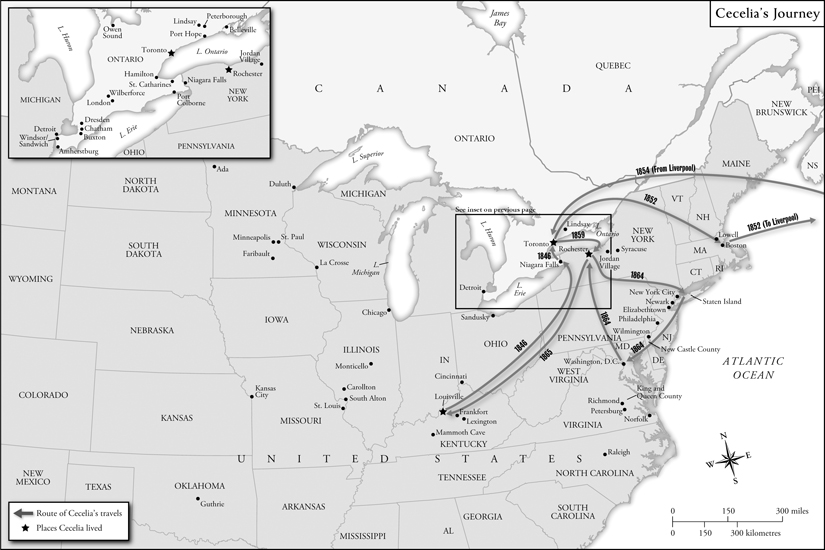

In 1846, conductors on the Underground Railroad helped Cecelia reach freedom in a dramatic escape via Niagara Falls. After that she resided in the cities of industrializing North America, primarily Toronto and Rochester, New York, with a sojourn in the great British port of Liverpool before returning again to Louisville.

The people with whom Cecelia was most closely associated, first in slavery and then in freedom, were also part of urban North America. Her owner, Fanny, was descended from two of the founding families of the pioneer West, both instrumental in the establishment of Louisville, her home on the Ohio River. Fanny was great-niece to William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and the great-grandmother of Rogers C. B. Morton, whom President Richard Nixon appointed Secretary of the Interior. Her people on her mothers side were the Churchills of Churchill Downs.

Although Cecelias first husband passed his childhood in a part of the South so rural that his home county only recently acquired its first traffic light, from the age of fourteen he lived in Richmond, Virginia. The city skills he gained during his years in the state capital shaped the rest of his life. Gaining his freedom in the most remarkable set of circumstances, Benjamin Pollard Holmes chose Toronto as his familys adopted home. It was there he learned to live as a free man.

Cecelias second husband was also a fugitive slave, from Newark, Delaware. Fleeing first to Toronto, he was later employed on a private estate on the outskirts of Rochester, New York. William Henry Larrison became part of that citys small but very active Black community. That was where he married the widowed Cecelia in 1862. After the Civil War, he and Cecelia took their children to Louisville, where her mother was. Although he sometimes took odd jobs on nearby farms, William spent the rest of his life in Kentuckys busiest port on the Ohio River.

Cecelias stepsons by Benjamin were urban too. Both trained in the profession their father had chosen for them in the great mill city of Lowell, Massachusetts. While they each spent time in small-town Ontario, one would end his life in Rochester while the other followed his white wifes family to Faribault, Minnesota, a boomtown on Americas western frontier. His sons would break the colour bar in Minneapolis as the first Black graduates of the University of Minnesotas medical school.

Cecelias only child to live to adulthood shared her mothers urban peregrinations, but after her mothers death she moved west. She went first to Guthrie, Oklahoma, where she remarried, and later to Kansas City when the Kansas City Monarchs of Negro Baseball fame were in their heyday. She and her husband made their home just down the street from smoky nightclubs where Scott Joplin had played ragtime and jazz musicians were inventing the Kansas City sound.

Because of her intensely urban experiences, Cecelia was at the epicentre of the social, economic, religious and political transformations of her age. In the ever-changing kaleidoscope of North American race relations both before and after the Civil War, she and her contemporaries were among the voices for change that emanated from the soul of Black America. These included a persistent drive for self-betterment, for respectability, piety and industry, to prove that people of African descent were as worthy to take up the mantle of citizenship as were their white contemporaries. Yet Cecelias whole life was played out against a backdrop of law and custom founded on white supremacist principles.

As is the case with so many of our proud female ancestors, no documents record Cecelias personal engagement in activism and protest. But she was among what one historian calls the great silent army of female abolitionists. It was women like Cecelia who provided to the refugees from bondage they found at their door the shelter, clothing, food and friendship needed to get them on their feet once they reached Canada. Working in tandem with the men they married, these women were essential cogs in the workings of the Underground Railroad. Like Cecelia, many held full-time jobs, cared for their families and still found precious hours to establish and support church-based self-help, benevolent, fraternal and self-improvement groups that were foundational to Black city life on both sides of the long border separating Canada from the United States.