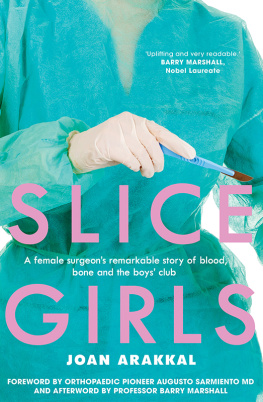

SLICE GIRLS

JOAN ARAKKAL

First published in 2018 by Impact Press

an imprint of Ventura Press

PO Box 780, Edgecliff NSW 2027 Australia

www.impactpress.com.au

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright Joan Arakkal 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any other information storage retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

ISBN: 9781925384598 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925384604 (ebook)

Cover and internal design by Alissa Dinallo

DISCLAIMER

I have tried to recreate events, locales and conversations from my memories of them. In order to maintain their anonymity, in some instances I have changed the names of individuals and places and I may have changed some identifying characteristics and details such as physical properties, occupations and places of residence.

Joan Arakkal is an orthopaedic surgeon who grew up and trained in India before moving to the UK where she was admitted as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. She later migrated to Australia where she currently works. She is the recipient of several academic and research awards in India and in Australia. She lives in Perth with her husband and two children.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Slice Girls is the type of autobiography where the reader is uninterruptedly fascinated by the description of events that Doctor Arakkal presents with veracity and honesty. Her professional concerns are skillfully mixed with colorful comments of a non-medical nature.

Although the main theme of the book relates primarily to women in orthopaedics, the books message is readily applicable to other branches of the medical profession. The discrimination to which women are in various degrees subjected illustrates the seriousness of the situation.

As a foreign-born woman with a non-western ancestry and a member of the female minority within the practice of medicine, the obstacles Doctor Arakkal encountered while trying to earn a deserved place in the field were painful, to say the least. However, the manner in which she confronted them belonged within the highest moral and courageous categories.

To a great degree, she finally succeeds in officially entering the male-dominated field, but many of the difficulties existing within the profession remained. She learns that the situation in which she functions encourages many to abuse the system by carrying out unnecessary nonsurgical and surgical treatments motivated by an insatiable hunger for profit.

Doctor Arakkal expresses concern over the fact that the obsession with profit in orthopaedics and the resulting shortage of members interested in basic research, has transferred, to a high degree, this important field to other disciplines. The ultimate consequences of such erosion is likely to weaken in a permanent manner the prestigious, traditional orthopaedic discipline.

Suddenly, Doctor Arakkal is diagnosed with cancer. The bad news does not deter her from continuing to function in an exemplary manner. To make matters worse, after a few years of relative optimism, she is diagnosed with metastatic disease.

In a stoic, resigned manner, she perseveres and continues to live a most professional life. That is the life she lives today.

As a highly sophisticated physician, Doctor Arakkal knows there are subtle as well as obvious differences in the condition of orthopaedics and that of its practitioners around the world. This reality does not preclude the possibility that unanticipated governmental, social or economic evolution could lead to radical changes, similar to those experienced in some nations. The lessons she articulates should help address the discrimination against female orthopaedists around the world.

The masterpiece of Slice Girls should be brought to the attention of not only women planning to enter the field of orthopedics, but also to others seeking a professional career in other branches of medicine, as well as to the overall population, in order to prevent as much as possible the further unfolding of this undesirable scenario.

AUGUSTO SARMIENTO MD,

EMERITUS PROFESSOR AND CHAIRMAN OF ORTHOPAEDICS

UNIVERSITIES OF MIAMI AND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

PAST PRESIDENT OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ORTHOPAEDIC

SURGEONS AND THE HIP SOCIETY

PROLOGUE

A hush settled over the audience as the stage curtains parted. To the faint strains of the vina, the silhouette of the dancer slowly came to life. Gradually, the music and the dance gathered pace and the lights shone brighter. I watched as my daughter gracefully performed the Tandava, the dance of Shiva. Shiva the creator, the preserver and the destroyer came to life as she carried us into the cosmic reality of our existence both small and infinitely vast at the same time.

The lights caught the necklace adorning her long neck. The bells on her anklets chimed to the rhythms of the tabla. As the rich hues of her silk sari fanned out, the synthesis of the masculine and feminine energies of the universe played out in the concept of Ardhanarishvara half man, half woman, each one incomplete without the other. My husband squeezed my hand gently. Our daughter would graduate in Bharatanatyam, the oldest classical dance tradition of India. Bharatanatyam encompasses bhavam, ragam and thalam expression, music and rhythm.

Two years earlier, I had attended my daughters law school graduation ceremony. Id been filled with pride this passionate young woman had innumerable plans and aspirations about how to make social changes and how to rally youth involvement with the older members of the society. Her grandparents had nurtured her through her growing years and she was eager to encourage the sharing of wisdom across the generations. I knew she would accomplish some of her dreams sometimes exceeding her imagination, sometimes having her dreams dashed, sometimes finding her rhythm and sometimes missing the beat.

Today my heart swelled with a different kind of pride. She was graduating in an art form that originated thousands of years ago. Dancers carved into the rock surfaces of temples had stood in their various poses beautiful and sensuous, frozen in eternal time, inspiring future artists to step out onto the world stage. Indian families who left their homeland have carried with them a fierce need to preserve their cultural ties. Although the more modern dancing of Bollywood has caught the fascination of the Western world with lively music, energetic movements and sugar-candy themes, the pursuit of classical dance remains more challenging.

As my daughter placed her hands elegantly in namaste and bowed deeply to the audience, a collage of my life flashed through my mind. The lights dimmed once again and applause filled the auditorium as the curtains came down. A powerful thought pressed itself upon me. Had I, too, come to my last song? There was no sadness in this thought. In Hindu thinking, life as we know it is an illusion one of pain and triumph, colour and music, earth and fire emanating from the cosmic Tandava of Shiva. Throughout my own personal, illusory, cosmic existence, I had danced fearlessly and joyously, untouched by the fire that sometimes raged nearby.

If the curtains came down on my life at that moment there would be little regret. Bestowed with the gift of life, I had danced through its various stages a childhood replete with innocence, fun and adventure, nestled in the warmth and love of a family who cherished me through my various teenage moods and blues. The love of a brother whose staunch faith in me kept me from falling when I tripped, and the love of a man carefully chosen for me by my family. The blessings of being a mother to a daughter and a son. The destiny that saw me birthed on the ancient soils of India, the travels that took me across the world and the good fortune to call Australia my adopted home. The privilege of a vocation that filled me with awe and gratitude.

Next page