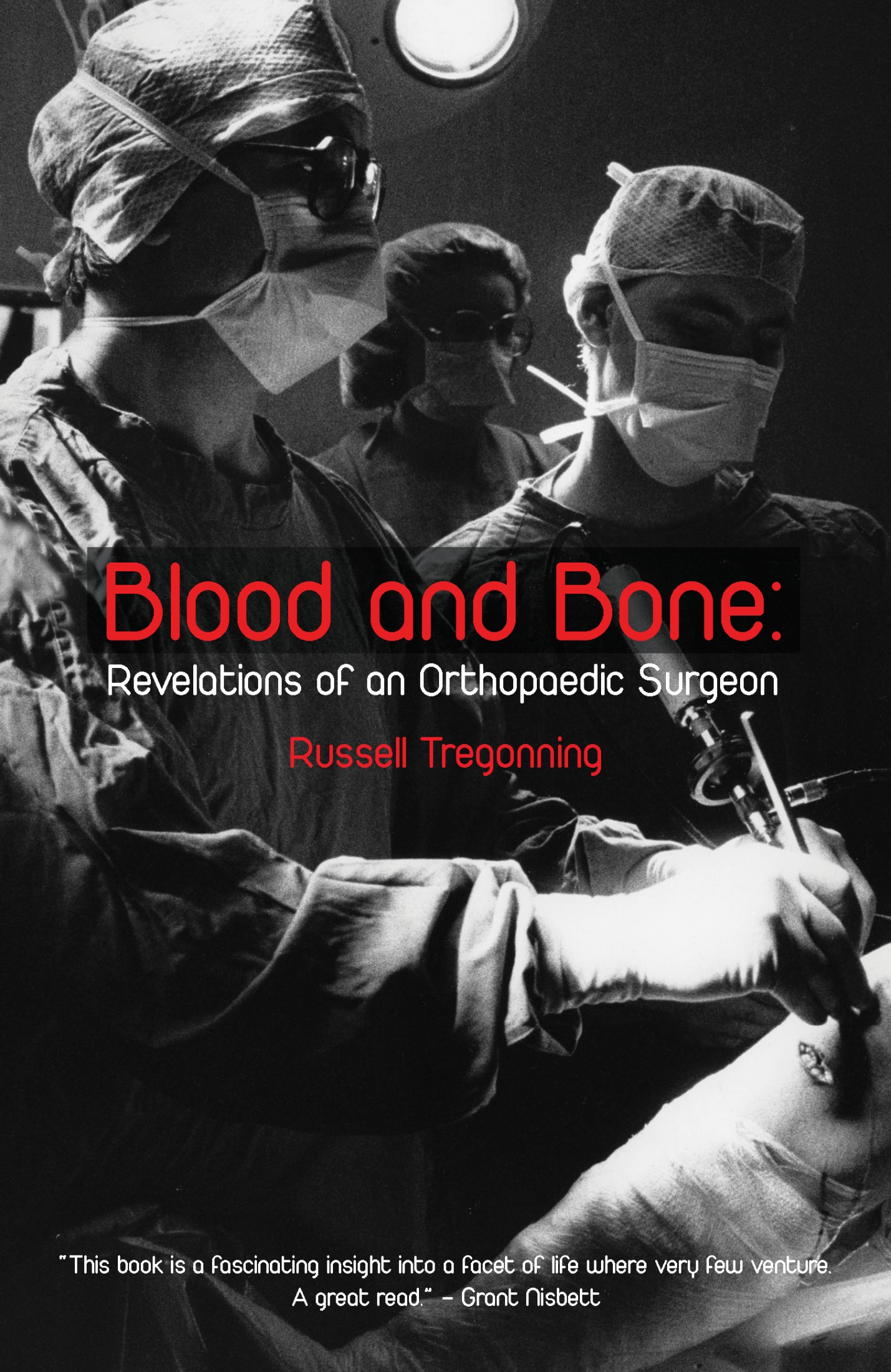

Blood and Bone:

Revelations of an Orthopaedic Surgeon

Russell Tregonning

First published in 2022 by Atuanui Press Ltd

1416 Kaiaua Road, Mangatangi, Pkeno, 2473

www.atuanuipress.co.nz

Copyright Russell Tregonning 2022

I sbn : 978-1-99-115914-4

Cover photograph by Louise Goossens

Cover design by Ellen Portch

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced without prior permission from the publisher, except as provided under New Zealand copyright law.

1416 Kaiaua Road, Mangatangi

New Zealand

www.atuanuipress.co.nz

Contents

For Pamela, my rock

Authors Note

The clinical case reports and other historical descriptions in this book are based on real events. I have changed the names of most patients and some colleagues and at times altered details to protect the privacy of patients, colleagues and their families.

The Final List

Bowen is a small private hospital in a peaceful setting among green hills. Its 2014 and Im about to start on the first case of my last operating list. I have worked in this hospital for 30 years, adding private practice to my public hospital work. In the past nine years, I have done all my surgery here.

My patient, Gill, is twenty-two. Six months ago she tore the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in her knee while playing netball. Ligaments are fibrous rope-like structures attached to bone on either side of joints; they stabilise the joints by restraining unwanted movements. The ligament Gill has torn is the weaker of the two crossed (therefore cruciate) ligaments that prevent abnormal front-to-back and rotational movements between the two longest bones in the body, the femur and the tibia. The longer the bone the more force it can exert at the joint. The forces that this ligament must resist, particularly in sport, are huge.

My job is to reconstruct the torn ligament. New Zealand surgeons perform over 3000 such operations each year. About 80 percent of the injuries occur in sport most often in rugby, then netball and football. I know from my own cases that theyre mainly caused by the person falling awkwardly from a leap. A sudden twist is also common, particularly if the person also plants their foot and stops suddenly.

I have several times visited a fellow knee surgeon, John Bartlett, in Melbourne. One time, John took me to watch the grand final of Australian rules football at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Aussie rules is a contact sport played by two teams of 18 on an oval field. I found out why some New Zealanders refer to it as aerial ping-pong: players repeatedly propel themselves skyward. Gravity operates in Australia, so these tall lithe athletes must then hit the ground and sometimes they are out of control, particularly if theyve been jostled while airborne. The game therefore provides knee surgeons with a rich harvest of ACL injuries.

John was team surgeon for Collingwood, one of the finalists. He kept pointing to his patients he seemed to have reconstructed the knees of about half the team. I later observed him operating. His technique involved using a strip of tendon harvested from the front of the kneecap and the tibia below. Until then I had used a technique I had learnt in Canada a decade before, taking a strip of tissue from the side of the thigh.

This tissue was weak, so I would have to harvest a long, wide strip. This left a visible scar, and in some people a bulge. Usually this could be hidden by clothing, but it was obvious when the person wore shorts. One patient told me, I like to show my friends my shark bite scar. I didnt think this did my reputation much good. I was keen to learn Johns new technique, which was less disfiguring.

Some people cope quite well without a functioning ACL, particularly if they build up muscle and avoid sports that involve jumping or sudden changes in direction. However, Gill is keen on netball and cant bear the thought of giving it up. Im completely sympathetic when I was young, rugby and other sports played an important part in my life but I tell her that if she continues to play netball and falls repeatedly, there is a danger of more and serious damage to many of her knee structures, and eventually permanent injury to the glassy and extremely slippery cartilage covering the bones inside her knee, a condition called post-traumatic osteoarthritis.

Gill has choices to make. The first is whether to have surgery. If she decides on this, the second is whether to have me use tendons from the front or the back of her knee.

I explain the pros and cons of surgery. Like most patients, Gill is unsure. She poses a question I commonly have to answer: What would you do? I tell her that these days I only cycle or walk for exercise so I would go for maximum muscle build-up and modify my activities. But her needs, as a young active athlete, are completely different. If you want to get back to netball, I recommend surgery, I say.

Knee tendons have fibres that are predominantly linear: they are designed to transmit muscle power to bend and straighten the knee. By contrast, the anterior cruciate ligament is a beautifully complex structure of fibres of various lengths curling around each other, perfectly made for the job of restraining the movement of the knees long bones, which can twist on each other as well as bend and straighten. Most ACL reconstructions result in a more stable knee, but the knee is never as good as the original uninjured joint. The graft may stretch with time, particularly if not implanted precisely. There may be pain in the sites where the material has been harvested, and numbness in the front of the knee, making kneeling uncomfortable. Also, if Gill plays netball there is a chance the graft will rupture.

We discuss the different techniques. I tell her I have about the same results for each, but fewer complications with hamstring tendons from the back of the knee. Even so, tendon grafts are relatively poor replicas. Not surprisingly they can fail to give a perfect result. But not always. Recently I met 44-year-old James in my fracture clinic. He had come with a minor fracture after falling off his mountain bike. When I introduced myself, he immediately said, I know you you operated on my knee 20 years ago. I went back to play basketball nine months after the operation and played intercity A-grade twice a week for eight years.

He reminded me of his dramatic injury. I suddenly changed direction. There was nobody near me. My knee wobbled and collapsed I felt as if Id been shot. From his scars it was obvious Id used a patellar-tendon graft. My examination showed it was intact. The knee was stable, two decades after reconstruction. My step was light for the rest of the clinic.

For patients to qualify for surgery, they need to undertake a vigorous exercise programme. Gill tells me shes had an extensive course of physiotherapy to strengthen her leg muscles. She also bikes and swims, both ACL-friendly activities. But her knee is still unstable: a sudden twist or sharp movement can cause her to drop to the ground in pain. Shes mystified as to how one simple fall has spelled the end of her active lifestyle. There was no one even near me when it happened, she says. I just landed awkwardly from a leap and felt a snap in my knee. I thought Id broken something, but the X-ray was normal. Now when I fall, it feels as if my knee goes out of joint. It swells up immediately. I cant play ping-pong, let alone netball.