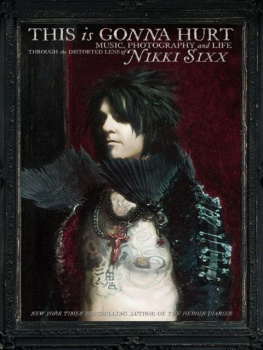

Dr Nikki Stamp FRACS is a cardiothoracic surgeon, one of only thirteen female heart surgeons in Australia. She has a strong desire to change the way we think about health by making it accessible and achievable. She is currently studying a PhD and has appeared as host of ABC TVs Catalyst, Operation Live and many other TV segments. Her writing has featured in Washington Post, Mamamia, Sydney Morning Herald, Huffington Post and The Guardian. Scrubbed is her third book.

Also by Dr Nikki Stamp

Can You Die of a Broken Heart?

Pretty Unhealthy

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

The information contained within this book is not intended to replace medical advice or to be relied upon to treat, cure or prevent any disease, illness or medical condition. The author and publisher claim no responsibility to any person or entity for any liability, loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly as a result of the use, application or interpretation of any material in this book.

First published in 2022

Copyright Nikki Stamp 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 760879 41 9

eISBN 978 1 76106 428 9

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Design by Committee

Cover image: Jan Halaska/Alamy

This book is dedicated to the true heroes in medicinethe patients and their loved ones. Thank you for your trust, your teaching and your inspiration that, despite the most challenging circumstances, give us all hope.

Over the years, I have been privy to some of the most private moments of peoples lives. Likewise, this book contains some things that I have seen and feltmy inner-most thoughts and fears, my experiences or those of my friends and colleagueswhich I never thought I would share. All of the stories in this book are based on real events, but to protect everyone involved, names, details and times have been altered, and some stories are a blend of several experiences of my own and of other peoples. Unless I have express permission from a person to include their name or story as it actually happened, I have taken artistic licence to keep secrets that need keeping.

People often ask if working at a hospital is like TV.

Most people, thankfully, dont have much to do with someone like me. Lets be honest: nobody really wants to meet a heart surgeon, especially not as a patient. Most of what you think happens in a hospital might have come from watching George Clooney in ER or the interns of Seattle Grace Hospital using the on-call rooms for something other than sleeping in Greys Anatomy. Maybe you recall seeing your local doctor, whiling away the time until your name was called, reading tabloid magazines that are at least five years out of date. In some doctors waiting rooms, Prince William and Kate Middleton are still on a break.

I want you to disregard everything you think you know about life inside a hospital. Theres no Dr House on a walking stick, hurling abuse at patients. No one is popping pills and getting his team to break into peoples homes to diagnose something weird and wonderful. Nor is hospital life punctuated by a series of intense relationships between unbelievably good-looking colleagues, which are paused only occasionally to care for the sick and injured.

Were not the heroes that TV would have you believe, but thats not to say that life inside a hospital is any less interesting, at least some of the time. In reality, life inside a hospital and the experiences of people like me, I think, are far more interesting because they are real. Life in a hospital is everything from mundane to thrilling, with moments of even sheer terror or unbridled joy. There are definitely heroes in our midst but they lack the histrionics of the doctors on medical shows that so many people love.

For whatever reason, stories from medicine have always been popular except among doctors. Generally, doctors hate medical stories but we still consume those from our own. When I was in medical school, there was a book that all of the older doctors and professors told us to read because it was a real look at what life was like inside medicine, away from the bright lights of Hollywood or the idealism that permeated medical school. (For more on the inner workings of an ICU, I highly suggest reading Critical by my friend and colleague Dr Matt Morgan.)

The House of God was written by Samuel Shem (the nom de plume of psychiatrist Stephen Bergman) and detailed the journey of a fresh-faced newly minted doctor as he navigated his early days in the profession. While he starts out naive and idealistic, his story twists and turns, diving into deep depression and reaching heady levels of ambition. Ultimately, in his fictionalised account of his first year as a doctor, he is ground down by the system. The politics, the loss of life and the dehumanisation of the protagonist ultimately culminate in Shem turning his back on hospital medicine to pursue a career in psychiatry where narcissism, callousness and a lack of care for ones own safety and wellbeing are notably (and happily) absent.

Among medical students and doctors, The House of God has a cult-like following. We recite lines from the book such as the Laws of the House of God, a set of thirteen salacious rules born of cynicism for the system we work in. They can only hurt you more or The only good admission is a dead admission speak to the dark humour of the book but also are a result of a system that quite often erases any empathy for other people, particularly and most concerningly for your colleagues.

As we progress through our careers, The House of God sometimes goes from being a darkly satirical commentary on the pitfalls of the culture of medicine to being semi-autobiographical for many of us. I dont know very many doctors who hate medicine or wish to be removed from their patients and the altruism of our profession, but I know plenty who have been broken or damaged by the system. The politics of medicine, however, are what hurt us: the interpersonal nonsense, the inhumane hours and lack of sleep, the separation from our friends and family, the chronic underfunding of some areas of health care and the futility of fighting the bureaucracy.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, health care was thrust into the spotlight. All of a sudden, as the world grappled with a new normal, it became evident that doctors, nurses, orderlies, allied health staffin fact, anyone who worked in health carewere facing an unfathomable task in defeating this pandemic. Globally, news outlets began running features on the brave front-line healthcare workers who were placing themselves at risk every day in COVID-19 wards. Thousands of healthcare workers around the world succumbed to the deadly infection.

Next page