To Hannah, Janis and Cara.

Prologue

The howling wind tore into me, pressing my down clothing against my body and driving spindrift into my face, spindrift that stung like needles any skin Id left exposed. The beam from my head torch punctured the black night, a bright arc in the freezing temperatures. Snatched, foreshortened views through my goggles revealed the vast Rupal Face below me, the longest vertical drop in the world. I was just a dot, alongside five more dots, traversing above a menacing void.

I kicked my crampon front points into the ice as precisely as I could, and balanced delicately on rock ledges. I jammed my mittened hands into snow-encrusted cracks in the rock, or twisted the pick of my ice axe into thinner cracks, torquing the shaft to give me some purchase, or else hooked the pick over a ledge, metal scraping against rock, a noise full of our determination.

Despite the high altitude and hostile winds we were moving efficiently, with the steady progress of a single-minded team. We had left our bivvy tents at one oclock in the morning and now daylight was starting to break behind the silhouetted mountain horizon. At this moment we reached the first pronounced bump on our way to Nanga Parbats summit.

Around us, the high summits lit up with the suns first rays. Above, the rugged profile of an outrageously steep and drawn-out ridge came into view. There was nothing tedious or straightforward here, just continuous technical climbing at extreme high altitude broken up by two steep walls with terraces and ramps of easier angled snow. The towering summit dominated our ambitions, holding a mastery over us, testing our confidence, threatening our hopes. We still had so far to go.

Two of our group, Cathy ODowd and Lhakpa Nuru Sherpa, now turned back, a little demoralised, admitting exhaustion and acknowledging defeat. They showed adispassionate resolution in announcing their decision, a resolution that impressed me, and I wished them well as they began making their way back to camp. I watched them briefly as they headed down and saw at a glance how far wed come together.

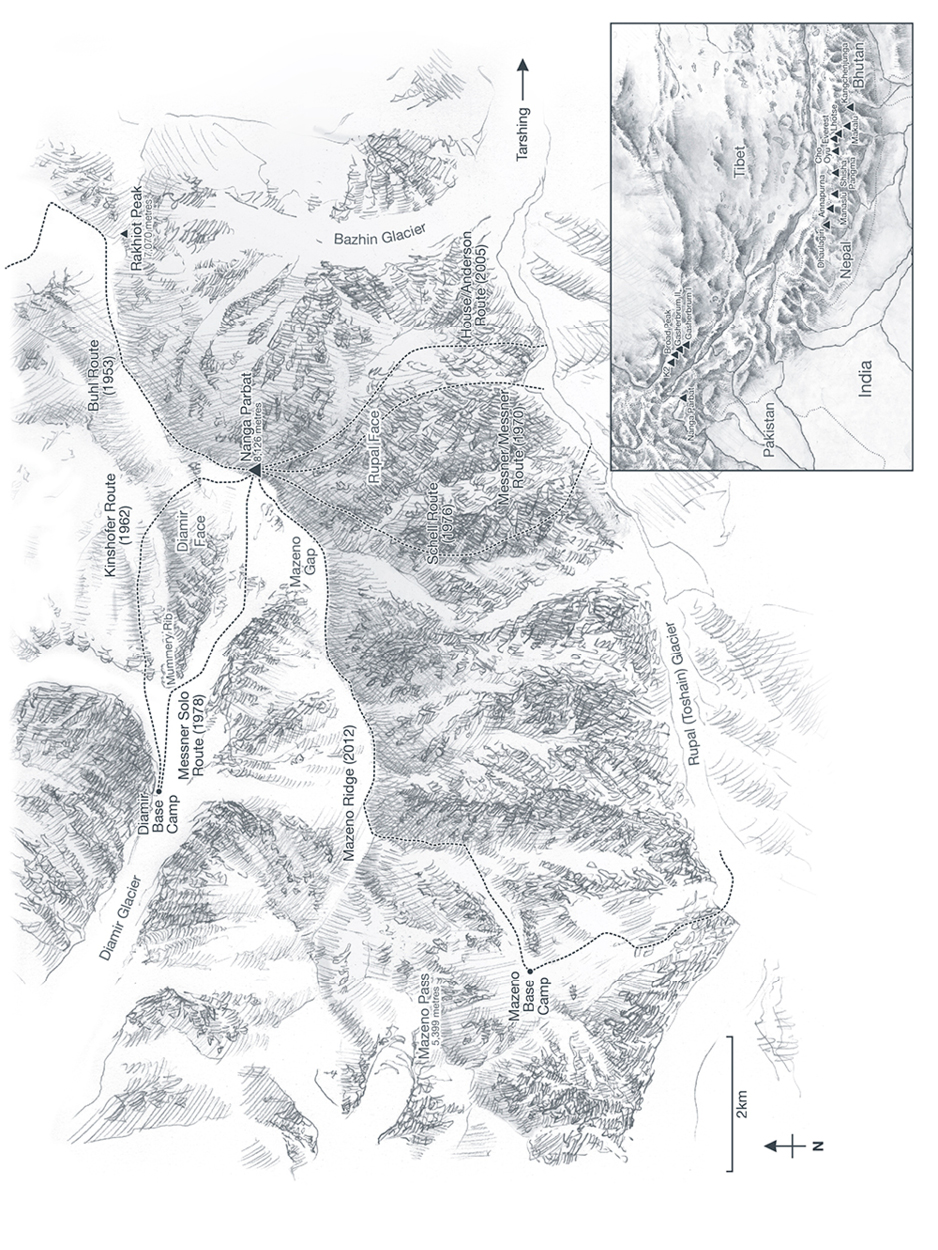

In front of Cathy and Nuru, as they descended, was the apparently endless objective we were attempting the Mazeno Ridge. It seemed to reach out forever, on and on over a series of eight separate summits, each over 7,000 metres high, stretched out over ten kilometres. It is the longest Himalayan ridge at this altitude yet climbed. Together, the six of us had spent nine days patiently working our way along it, sitting out bad weather, fighting through deep snow and eventually reaching a notch in the ridge below the final climb to the summit the Mazeno Gap. That meant an average of barely a kilometre a day. For the final, exhausting climb to the top, we faced another three kilometres and 1,300 metres of ascent.

The four of us who remained continued upwards; two separate teams of two with the will to push on and complete this majestic unclimbed ridge in the sky. I was tied in with my old climbing partner Rick Allen. Wed shared plenty of adventures in the past, had even climbed Nanga Parbat together once before and had two lifetimes of experience behind us. What were we doing here, middle-aged men deep into our fifties, faces turned against the inhospitable weather, pushing our bodies to the limit when most of our contemporaries were happily retired?

Our Sherpa friends Zarok and Rangdu took a parallel line up the awkward mixed ground of rock and snow and then we moved in semi-organised unison up a steep and loose rock wall, endeavouring to avoid the occasional loose stones which fell like shrapnel. Dislodged stones crashed into the wall and ricocheted off on new trajectories, whistling through the air as they plummeted. We continued towards the Merkl Notch and another rock wall which led towards the south summit.

Slowly, so slowly in the thinning air, it became obvious we would not have time to surmount this difficult obstacle and continue our climb up the snow couloirs beyond to reach the ninth-highest summit in the world. Growing despondent and exhausted, there was little option but to turn back. Now it was our turn to face defeat. We had almost touched 8,000 metres, but we were too late, too cold and too worn out to continue.

Standing motionless in our steps, our conversation was amicable, short and realistic; but at some level I felt a little sour two of us so tempted to push on, two wishing to turn back. Knowing full well that by nightfall we would be exhausted and trapped above 8,000 metres without a stove, food or shelter if we continued, better sense and collective survival instincts prevailed. Zarok and Rangdu announced that they were done. They would go down and would not try again.

Rick and I kept our counsel. We had no ingenious plan. Although steadfast and keen to continue, we had no intention of being martyrs to this climb. As expedition leader, hearing what the two Sherpas said, I simply acknowledged it was probably best to head down, retreat as a unified team and wait to see what the future might bring. We turned around dejected but knowing we had tried. The retreat back to the bivvy site would not be straightforward.

To save time, I suggested a short cut, traversing an easy snow ramp to a small notch where a vague narrow ledge divided the rock wall we had climbed earlier. Below and above the ledge was a steep cliff. I led down, using my ice pick to hook ledges, my crampons stabbing placements on the snow-encrusted and brittle rock. The others tentatively followed, questioning the wisdom of my route, wondering if my chosen line would get easier or harder.

The ledge continued. On one small but awkward overhanging step, I placed my ice tool above me, torquing the pick and holding tight to the shaft. I lowered my body downwards, trying to place my clumsy high-altitude boot and front points on to a tiny protrusion of rock. From here I hoped to transfer my weight and step down on to a slightly wider ledge, but the torqued pick pulled out from the crack and down I fell, the ragged rock tearing my down trousers. A plume of the finest quality duck down filled the air and gasping with hypoxia I breathed it in, filling my throat with feathers.

Choking, I spat them from my already dehydrated mouth. My legs floundered against the rock as Rick held the rope tight to stop my fall. Regaining composure and breathing more regularly, I led on down the thirty-five-degree traverse, flicking the rope over small rock flakes. If I fell again there was a chance the rope would catch on the flakes, reduce the fall and stop me pulling my partner down the sheer cliff with me. The climbing felt intense and as I cleaned the soft snow off ledges, looking for cracks in which to place my ice axe pick, my tired body buckled with stress. We had now been climbing continuously for fourteen hours: this was our eleventh consecutive day, and ten of those days had been at around 7,000 metres.