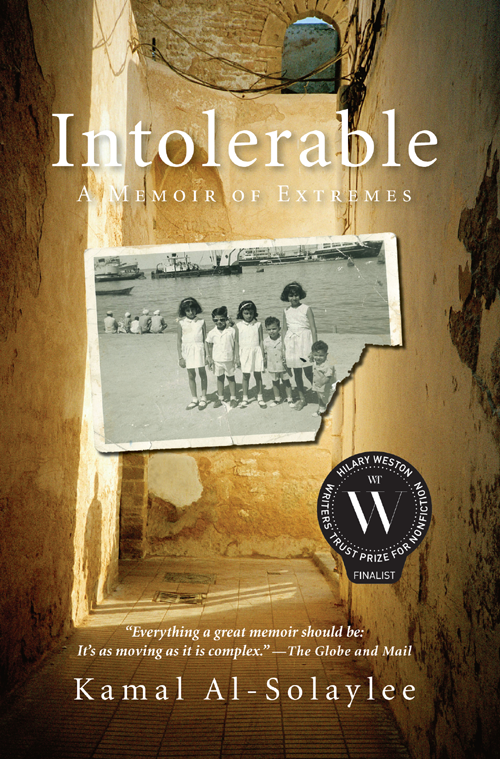

I am the son of an illiterate shepherdess who was married off at fourteen and had eleven children by the time she was thirty-three.

My mother, Safia, was born and raised in Hadhramaut, a part of my home country of Yemen that is better known today as the birthplace of the bin Laden clan. When she and my father, Mohamed, were married in the fall of 1945, in the port city of Aden, then a British protectorate, he was fresh off serving a stint in the Allied army and she had just reached puberty mere months before. A year earlier, she once confided to me, she had listened to the radio for the first time in her life and her older sister, Mariam, had talked of something called the cinema. The voice of an Egyptian singer, whom she identified years later as Oum Kalthoum, flowed through the airwaves when she walked past a little makeshift work station in the hills of Hadhramaut. Another Egyptian artistAnwar Wagdi, Egypts answer to Gene Kellywas starring in an early musical melodrama, which she never got to see but had Mariam re-enact several times during their breaks from tending sheep.

Little did Safia know then that her father was waiting for her first period, her first tentative step towards womanhood, to pair her off with the son of a co-worker of his in the civil court where both men served as guards. Safia would always muse about the fact that her father-in-law, Abdullah, kept watch over criminals, since Abdullah himself was a runaway from justice, having killed a man near the northern Yemeni town of Taiz as part of a long-standing tribal vendetta. Indeed, Abdullah ended up in Aden in the early 1910s while on the run from his victims family. He may have been sixteen or seventeen at the time. There was no way of telling his exact age, as birth certificates didnt exist at that time in Yemens history. He adopted the name Solayleealso spelled in English as Sulailifrom a small tribe that offered him shelter on their land near the border that divided what was then North and South Yemen. His family name, and by all rights mine, is Komeath.

On the rooftop of the family building in Aden in 1965, Safia holds me tight while she waits for the laundry to dry. She was an overprotective motherespecially of me, her youngest child.

Kamal Komeath. It would have had a theatrical ring to it, befitting someone who studied Victorian melodrama in England and made a living writing about theatre in Canada. It might even be easier to spell than Al-Solaylee, a last name that Ive always hated and spent most of my life enunciating one letter at a timein English and in Arabic.

Theres so much to a name in Arabic culture. Your name aligns you socially and politically with your clan or provides an escape from it. When we lived in Cairo in the 1970s, many of our middle-class Egyptian friends adopted foreign namesSusan, Gigi, Michelleas aspirations to a Western life. Arab nationalists preferred names that drew on local history: Salah, after Salah-ad-Din, who stood up to the Crusaders; or Gamal, after Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. Kamal itself means perfection, or the person who completes something and gives it the final push towards fulfillment. Its one of the ninety-nine holy names for Allah, although my understanding is that Im named after Kamal El-Shenawy, the Egyptian matinee idol of the 1940s and 50s, who happened to be my mothers favourite, once she experienced moving pictures for herself many, many years later.

The verb form of my name, kamael, means to fill in the gap or complete a story. To try to live up to the many meanings of Kamal, even subconsciously, is an attempt at self-destruction, one meaning at a time. Its a given that I am far from perfect, but to fill in the gap between my life now, as a writer and university professor in Toronto, and that of my parents and my siblings in Yemen is what makes this book a necessity and a daunting task. How can I write of a mother who lived and died without learning to read or write in her native tongue, let alone English, when I went on to earn a Ph.D. in Victorian literature? Is it still a gap between my mother and me when the distance is the equivalent of living in different centuries and worlds? I look at family photographs in my Toronto apartment and wonder what Safia would have made of everything around me if she were alive today. Shed be shocked to know how little food I keep in the fridge, or that Im a vegetarian. She was a consummate cook and never served a meal without two kinds of meat at least. She never thought that fish alone counted as a main course and served meatballs as a side dish to go with it. My apartment, decorated with modernist and minimal furniture and abstract art, would strike her as a work in progress. I can almost hear her say, Im sure youll buy more furniture when youve saved up some money. She associated weight gain with health and prosperity and was anxious when I went on a strict diet and lost thirty pounds between visits to Yemen.

When I last saw her, in 2006, she was far gone into Alzheimers, but she still found it perplexing that I owned a dog in Toronto. Get rid of him, she pleaded with me, without ever pronouncing his name. I could no more get rid of Chester than you could give up one of your children, I responded, knowing that appealing to her sense as a mother could still be effective. She nodded and drifted off into an incoherent story, the details of which I cant remember. To her, dogs were those vicious wild animals that occasionally attacked her sheep and bit her as a young shepherdess, or the dirty, rabid ones that roamed the back streets of Cairo and frightened her children every time they got close. What struck me then was her ability to bridge the gaps between her lives as a young girl, a middle-aged mother and now an elderly woman.

She was a pro at it.

Her entire married life was a desperate and difficult attempt at bridging gaps. In 1949 my father decided to study business in London for a year, leaving her behind with the first three children. She was eighteen. When my dad returned from England and started a business of buying and selling rundown propertiesan early local example of flipping, in todays real-estate termshe had developed a taste for the sophisticated English life. Until weeks before his death, in 1995, he was rarely seen in public without a shirt and tie. Traditional Yemeni clothesincluding the fouta, a skirt-like lower garmentwere strictly for home. He introduced cutlery to a household that enjoyed eating with their hands. Mohamed would often tell us a story of how, after several attempts to get his wife used to a knife and fork, he settled on training her to eat with a spoonat least when they had company. It was one of several and soon-to-be-growing gaps between my parents. A wife who was illiterate, and still a teenager in years if not life experience, hardly provided the necessary adornment for a businessman with career and social-climbing ambitions. Social standing hadnt counted for much in their parents lives; as long as a bride was young, virginal and from a good Muslim family the rest hadnt really mattered. He couldnt possibly divorce her, not with three children and a fourth on the way, and not since he seemed genuinely in love with her. As a stopgap, he taught her two English phrases, phonetically, so that if an Englishmanand there were many of them milling about Aden, which was then part of the British Empirecame looking for him, shed not let him down. Welcome was the first and easier of the two to learn. Just a moment followed a few days later. It wasnt exactly Henry Higgins and Eliza Doolittle but enough to keep him happy and her out of trouble.