Dedication: Despite Tapas

Helion & Company Limited

26 Willow Road

Solihull

West Midlands

B91 1UE

England

Tel. 0121 705 3393

Fax 0121 711 4075

Email:

Website: www.helion.co.uk

Published by Helion & Company 2011

Designed and typeset by Farr out Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Cover designed by Farr out Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Printed by Gutenberg Press Limited, Tarxien, Malta

Text and maps Michael Embree 2010

ISBN 978 1 906033 24 8

Paperback ISBN: 9781909384392

ePub ISBN: 9781909384736

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system,or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of Helion &

Company Limited.

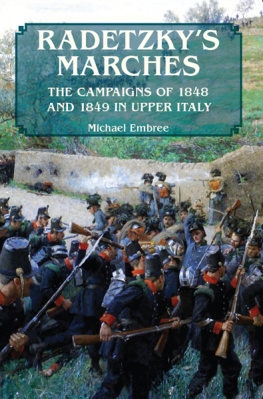

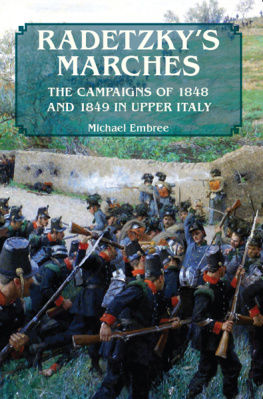

Dustjacket illustration: The Kaiserjger at Pastrengo, 30 April 1848. Painting by Rudolf

von Ottenfeld (reproduced courtesy of the Kaiserjgermuseum Innsbruck).

For details of other military history titles published by Helion & Company Limited

contact the above address, or visit our website: http://www.helion.co.uk.

We always welcome receiving book proposals from prospective authors.

List of Illustrations

Colour section

Images within the text

List of Maps

With special thanks to good friends Bruce Weigle, Bruce-Bassett Powell, and Tim OBrien for their invaluable help with the maps.

The following appear in the colour section:

Foreword

T his book focuses on the military campaigns for the control of Upper Italy during 1848 and 1849, or more specifically, Piedmont, Lombardy-Venetia, and the Tirol. Whilst there were clearly important links between the campaigns in Upper Italy and others in the rest of the Italian Peninsula, and indeed events throughout Europe, these will only be discussed in detail where they directly relate to these military campaigns.

In a letter to an Austrian diplomat in 1847, Prince Metternich, the Chancellor of the Austrian Empire, described Italy as a geographical expression. Subsequent events would prove the great statesman wrong. It would, indeed, prove that mid nineteenth century nationalism would eventually succeed, not only in Italy, but all over the continent. Whether, after the horrors of the 20th Century which flowed from it, this was a positive asset is perhaps at least arguable.

I have chosen to use names for place and geographical features which are, where possible, familiar to the English speaking reader. This may mean that they are unfamiliar or even comical to others. This decision, right or wrong, I made for clarity and consistency. Where there is not a commonly used English version, place and feature names reflect modern rather than contemporary borders. To avoid any possible confusion my aim has been to use only one name for any settlement or geographical feature. Should this decision offend any readers, my apology is here offered. There will certainly be instances where wrong, archaic, or local spellings are used, especially in an age before generally accepted written place-names existed.

This book is intended for the English speaking reader. Should it add any knowledge or interest at all to a wider audience, it will be a great bonus.

Any errors or omissions of any kind are, of course, my responsibility.

Acknowledgements

S tephen Allen, Renzo Barbieri, Bruce Bassett-Powell, Chris Bauermeister, Davide Bedin, Maurizio Bragaglia, Andrew Brentnall, Mrs. Elisabeth Briefer, Jean-Claude Brunner, Luigi Casali, Stefano Chiaromanni, Michael Gandt, Antonio Gatti, Alessandro Gazzi, Tom Hill, Eamon Honan, Glenn Jewison, Jean-Marc Largeaud, Arturo Lorioli, Tim OBrien, Stuart Penhall, Marco Pertoni, Mogens Rye, Ernesto Salerani, Jan Schlrmann, John Eric Starnes, Bruce Weigle, Marco Zaccardi, Andrea Zanini, and of course, Sally and Kathryn, who once again, put up with all of this.

Europe at the Beginning of 1848 and the Italian Dimension

The Long Peace

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 had convinced virtually all European statesmen that another similar hideous string of conflicts must never again be allowed to occur. It had particularly influenced Prince Metternich, the Austrian Chancellor, who would dominate the continent for over 30 years. With his British counterpart, Lord Castlereagh, he worked to establish a permanent alliance which would balance any ambitions by a single power, so ensuring peace. The resulting Quadruple Alliance of Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain lasted until 1822, when Castlereagh committed suicide, and Britain pulled out.

Liberalism and nationalism, the two major forces of the 19th Century, were anathema to Metternich, as they represented the misery and chaos of the French Revolution, and Empire. He watched with horror German university student demonstrations, which encapsulated both forces. Indeed, the excesses of revolutionary movements were brought forcibly home to him in 1819, when a playwright with conservative views, August von Kotzbue, was murdered in Russia, by a student, Karl Ludwig Sand. Sand was subsequently executed by the Tsarist authorities.

This affair had considerable consequences, as, at a conference held in the Bohemian town of Carlsbad that same year, the German Diet passed the so-called Carlsbad Decrees. These provided for strict press censorship throughout the German Confederation, and also for much closer supervision of universities. To many, Metternich was becoming reaction incarnate. In the internal affairs of the Empire, he had less success in influencing matters, especially after the death of his mentor, Franz I, in 1835. His successor, Ferdinand I, was severely epileptic. The Minister of Finance, Count Franz Anton von Kolowrat-Liebsteinsky, managed to use the absence of Franz to ensure that Metternich restrict himself to diplomacy.

Strife did not simply vanish in Europe between 1815 and 1848. There were conflicts involving Poland, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, and Italy during the period. Apart from Poland in 1830-31, these were not on a large scale, nor did they spread to encompass other states. All this would change in 1848.

By then, 74 year old Metternich had effectively held the lid on liberal and nationalist forces since Waterloo. Now, those forces were finally moving beyond his control. However, events would prove that they were by no means necessarily complementary.

When Paris Sneezes, Europe Catches a Cold

In a poor economic state, France, like most of the continent, had been badly affected by the disastrous famine of 1846. King Louis Philippe unwittingly combined this disaster with government policies which were increasingly disenfranchising the lower classes in favour of land owners, thus creating a wave of discontent throughout the country. Since political demonstrations were forbidden, a series of banquets were held, from the summer of 1847, at which criticism of the authorities was routinely made. Matters came to a head when the Government, in February 1848, banned such gatherings. At the same time, a section of his own Party, led by Adolphe Thiers, turned against the King

News of this caused some barricades to be erected in Paris, and some limited rioting took place. On February 23rd, the Prime Minister, Franois Guizot, resigned. As news of this spread, crowds gathered outside the Foreign Ministry. Troops positioned there, probably as a result of a mistake, opened fire, killing 52 people. This was the signal for barricades to rise all over the city, as people made their way to the Royal Palace.

Next page