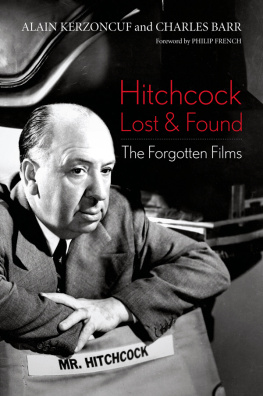

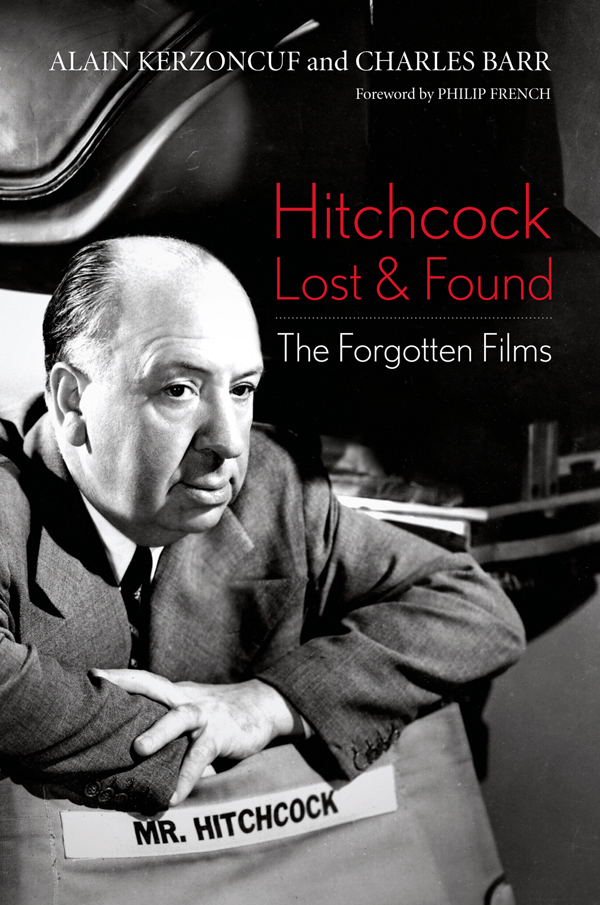

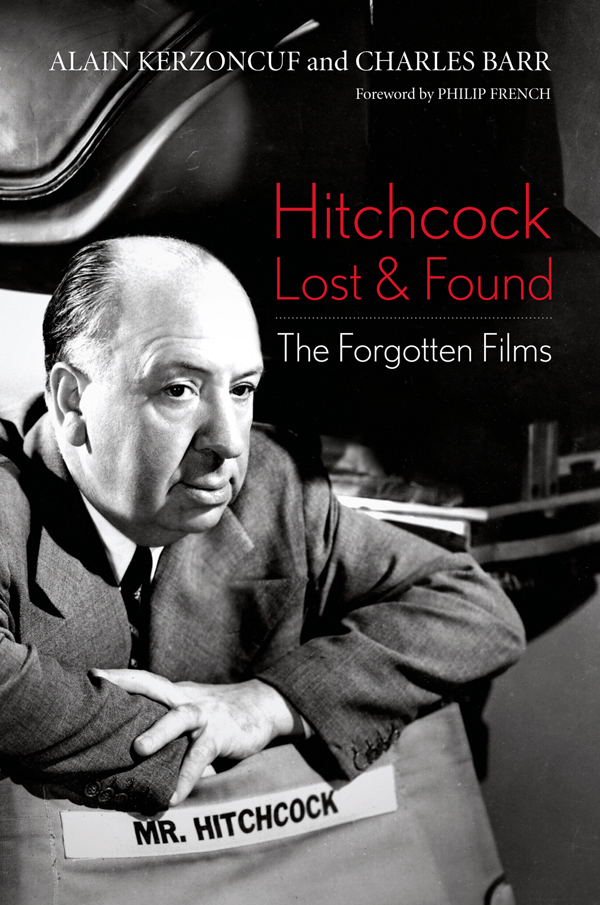

Hitchcock Lost and Found

Hitchcock

Lost and Found

The Forgotten Films

ALAIN KERZONCUF

and

CHARLES BARR

Foreword by

PHILIP FRENCH

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2015 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kerzoncuf, Alain.

Hitchcock lost and found : the forgotten films / Alain Kerzoncuf and Charles Barr ; foreword by Philip French.

pages cm. (Screen classics)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-6082-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6084-9 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8131-6083-2 (epub)

1. Hitchcock, Alfred, 1899-1980Criticism and interpretation. I. Barr, Charles. II. Title.

PN1998.3.H58K48 2015

791.4302'33092dc23 2014044816

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

To my wife, Valrie

A. K.

To my daughter, Stella

C. B.

Contents

by Philip French

Foreword

In this valuable contribution to Hitchcock studies, a book of equal interest to the academic world and movie enthusiasts, Charles Barr and Alain Kerzoncuf quote Paula Cohens confident claim that to study him is to find an economical way of studying the entire history of cinema. Hitchcock has been part of my own experience of the cinema since 1939, the year I turned six, saw Jamaica Inn on its initial release, noted the name of the director, and began to develop the instincts of a discerning moviegoer. But not so discerning that good taste prevented me from enjoying its stirring tale of wreckers and revenue men on the Cornish coast (where the previous summer Id spent my holidays) or saved me from being shocked like everyone else in the audience when Charles Laughtons Sir Humphrey Pengallan throws himself to his death from the riggings of the sailing ship. This would have been my first experience of the recurrent Hitchcockian motif of people falling from high places.

That year I committed to memory all fifty cards of movie stars given away with packets of Wills cigarettes, but Alfred Hitchcock was one of the only two directors I could name or recognize (the other of course being his fellow Londoner Charlie Chaplin). By the time I was ten or eleven I had learned a great deal about himfrom listening to adult conversations or being told about him by my parents (both of them habitual but uninquisitive moviegoers), reading advertisements, and seeing his films, and by general osmosisand I knew him to be someone of importance. He made signature appearances in all his movies, was a tubby cockney, had earned (or bestowed on himself) the sobriquet master of suspense, had been accused of dodging the war by leaving the country for Hollywood just before it broke out, and was the director of the first British talkie. I could describe characteristic touches (a truncated finger that identified a villain, a windmills sails turning in the wrong direction, a woman suddenly disappearing from a moving train) and came to see him as a man who liked peculiar challenges like setting a whole film on a lifeboat in the mid-Atlantic. The first two books on film I bought, both second-hand in 1949, were Roger Manvells seminal Pelican paperback Film (1944) and Charles Davys excellent anthology Footnotes to the Film (1938). The former contained the first filmography I ever read (actually called Some Directors and Their Films), listing seven Hitchcock films, starting with Blackmail, while the latter opened with a level-headed essay on the art and craft of direction, featuring a celebrated account of the way he shot the knifing of Monsieur Verloc in Sabotage, and a biographical note that omits mention of The Mountain Eagle and erroneously gives his date of birth as 1900.

Thus from the war years onward I followed Hitchcocks career as it unfolded: the post-Selznick liberation and return to England with Ingrid Bergman to make Under Capricorn; his response to 3-D (Dial M for Murder, not shown stereoscopically in Britain until 1983, but the only one that struck us as truly original) and then the widescreen (VistaVision only); and his exploitation of TV (Alfred Hitchcock Presents, a brilliant way of keeping his name before the public without compromising his theatrical work). An admirer of his films from childhood, I came to recognize a greater complexity in his work only as he and I got older. By the late 1950s I was working as a radio producer, and he appeared on several programs of mine, unforgettably revealing at the end of an interview about North by Northwest in 1959 that his next film, Psycho, will be my first horror picture. What really focused and crystallized my thinking at that time was being introduced to the work of French critics (the idea of Hitchcock as a Catholic artist and the concept of transference of guilt) and the appearance of Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmers Hitchcock, which I read in French with some difficulty in 1960. The launching of the auteur-oriented magazine Movie in Britain in 1962, several of whose contributors took part in my radio shows, involved me with British enthusiasts, culminating in the publication in 1965 of a book by one of its editors, Robin Woods Hitchcocks Films, the first proper study of the Master in English. Despite it being a modest paperback, the Observer was persuaded to let me write an admiring review of Woods wholly original work, which he was to expand and modify over the years (notably in connection with the Masters sexuality). It was followed two years later by Franois Truffauts book-length interview, Le Cinma selon Hitchcock, along with the Chabrol-Rohmer book (first translated into English as Hitchcock: The First Forty-Four Films in 1979 just before Hitchs death). These three books were to inspire first a stream and then a torrent of articles and monographs that would become the largest body of writing on any single filmmaker. I myself have made a few contributions, including a lengthy obituary for the Observer (4 May 1980). I called him our greatest filmmaker, fully the equal of our greatest living novelist, his fellow Catholic Graham Greene, who as a film critic was never generously disposed to Alfred Hitchcock possibly because of the close parallels between their careers. There will never be another career quite like his, I added, growing up with a new art, learning its every aspect as a young man, then living through the transition to sound, the arrival of TV and the widescreen, the relaxation of censorship, and staying at the top for fifty years, changing with the times, catering to new tastes, but remaining his own man.

Next page