Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Christopher Holt and Nina Ryan.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors and publishers of the following journals in which excerpts of this book first appeared: Agni Magazine, The Fourth River, and Accent. Building a House in the Woods, Maine, 1971 first appeared in Contemporary Poetry of New England. It was read at the inauguration of Governor John Baldacci in January 2003.

Quotes from The Hill Wife, The Need of Being Versed in Country Things, Birches, and Good-By and Keep Cold from The Poetry of Robert Frost edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1916, 1923, 1969 by Henry

Holt and Company. Copyright 1944, 1951 by Robert Frost. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Excerpt from Gettysburg: July 1, 1863 copyright 2005 by the Estate of Jane Kenyon. Reprinted from Collected Poems with the permission of Graywolf Press, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Autumn Lines and excerpt from High in the Mountains, I Fail to Find the Wise Man from Five Tang Poets, translated and introduced by David Young, Oberlin College Press, copyright 1990. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from Regarding Chainsaws from Collected Shorter Poems 19461991 by Hayden Carruth, Copper Canyon Press, copyright 1992. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from I Sleep a Lot by Czeslaw Milosz from The Collected Poems 19311987, HarperCollins Publishers, copyright 1988. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from Report from the Besieged City by Zbigniew Herbert from Report from the Besieged City & Other Poems by Zbigniew Herbert. Translated with an Introduction & Notes by John Carpenter and Bogdana Carpenter. HarperCollins Publishers, copyright 1985 by Zbigniew Herbert. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from Wise Blood by Flannery OConnor, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, copyright 1949, 1952, 1962. Reprinted by permission of the publisher and Harold Matson Co., Inc.

Excerpt from The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner by Randall Jarrell from The Complete Poems by Randall Jarrell, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, copyright 1968, 1969 and Faber and Faber, Ltd. Reprinted by permission of the publishers.

Excerpt from Hugh Selwyn Mauberley by Ezra Pound from Selected Poems by Ezra Pound, New Directions Publishing Corporation, copyright 1957. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766

www.upne.com

2006 by Baron Wormser

First University Press of New England paperback edition 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766.

ISBNs for the paperback edition:

ISBN-13: 978-1-58465-704-0

ISBN-10:1-58465-704-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-61168-383-7(eBook)

CIP data appear at the end of the book

This book does not purport to be an annal. As memory is subjective and partial, it has a fictive aspect. Names have been changed accordingly.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wormser, Baron.

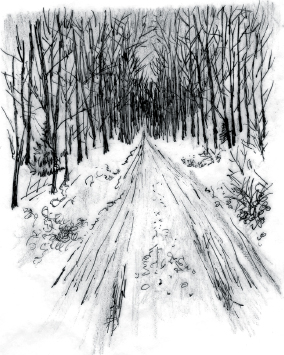

The road washes out in Spring : a poets memoir

of living off the grid / Baron Wormser.

p.cm.

ISBN13: 9781584656074 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN10: 1584656077 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Wormser, Baron. 2. Poets laureateMaineBiography. 3. Poets,

American20th centuryBiography. 4. Country lifeMaine. I. Title.

PS3573.O693Z46 2006

811.54dc222006017923

For Janet, Maisie, and Owen

Building a House in the Woods, Maine, 1971

A good uphill mile and a half from a not very good dirt road,

That distance on foot meaning a sort of mincing strut over frost heaves

And washouts across what had been a poor road at best fifty years previously,

Through tangles of witch hazel, alder and birch saplings andat this time

Of year in the low spotssucking gurgling mud: that expedition

Taking the better part of an hour to a ridge side where a few gaunt, disheartened

Apple trees and dead elms from the nineteenth century stood like blank-eyed

Sentinels and where you intended to build a house that would stare

Without curtains at a prospect of more ridges and then real mountains that

Receded to the serene distance of pale green eternity.

And why shouldnt love be made her e, meals cooked and consumed, fires stoked,

Children born who would have the bound less woods to learn from, who would feel freedom

In their footsteps and taste the calm thrill of dawn. Werent all of us

Young and able to split, hammer, haul, plant, saw, push, carry, lift, and

At the end of the physical day simply and sublimely sit?

We breathed the dank clean air, the thin sharp smells of pine woods and dead

Leaves and melting snow, and we star ted to whoop and jig for the vision of it,

The earth strength that we had lived too long without.

The Road Washes Out

in Spring

A POETS MEMOIR OF LIVING OFF THE GRID

Baron Wormser

University Press of New England

Hanover and London

W hat brought me to the woods was grief. My mother died of cancer when I was twenty-one. She was forty-eight. Hers was a protracted, harrowing death with remissions, tatters of hope, experimental treatments, and deep stretches of agony alleviated by morphine oblivion. For six years she was in and out of hospitals. I walked the long linoleum corridors and talked with the doctors, interns, and nurses about dosages and the weather, about radiation and baseball, about surgery and traffic jams. For every dire perplexity a mundane tangent beckoned.

I sat by her bedside reading aloud to her from her favorite distractionVictorian novels. She was wild about Anthony Trollope. The vicars and lords and widows whose cordial yet machinating lives Trollope recounted seemed reasonably settled, yet being people they managed to muck things up. Both the settled aspect, the golden dust of autumnal England, the material weight of furniture and dresses and jewels, and the making a mess of things pleased my mother. She had lived, but she wanted to live more. She had wanted to visit Europe and view cathedrals and parsonages. She had wanted to breathe the ripe air of history. Now there were a hospital bed and duration and books.

I lived with death on a daily basis, a companion of sorts, mute but tireless. When I shaved in the morning or stopped at a drive-in to get a hamburger or walked from one class at the university to another, I felt deaths presence. In that sense, part of me was dying with her as I watched her valiantly struggle with her diseases mindless depredations. What did those dispiriting cancer cells know? How many nights had I sat by her bedside when she was asleep, too weary and sad to pick myself up, and listened to the noises of the hospital, the squeak of shoes and the rolling creak of gurneys, as if they might bring me an answer?

Next page