Contents

Guide

Page List

Also by Ray Connolly

FICTION

A Girl Who Came to Stay

Trick or Treat?

Newsdeath

A Sunday Kind of Woman

Sunday Morning

Shadows on a Wall

Love Out of Season

NON-FICTION

Stardust Memories anthology of interviews

The Ray Connolly Beatles Archive

Being Elvis: A Lonely Life

SCREENPLAYS FOR THE CINEMA

Thatll be the Day

Stardust

FILMS AND SERIES FOR TELEVISION

Honky Tonk Heroes

Lyttons Diary

Forever Young

Defrosting the Fridge

Perfect Scoundrels

TV DOCUMENTARIES

James Dean: The First American Teenager

The Rhythm of Life three-part music series

PLAYS FOR RADIO

An Easy Game to Play

Lost Fortnight

Tim Merrymans Days of Clover (series)

Unimaginable

God Bless Our Love

Sorry, Boys, You Failed the Audition

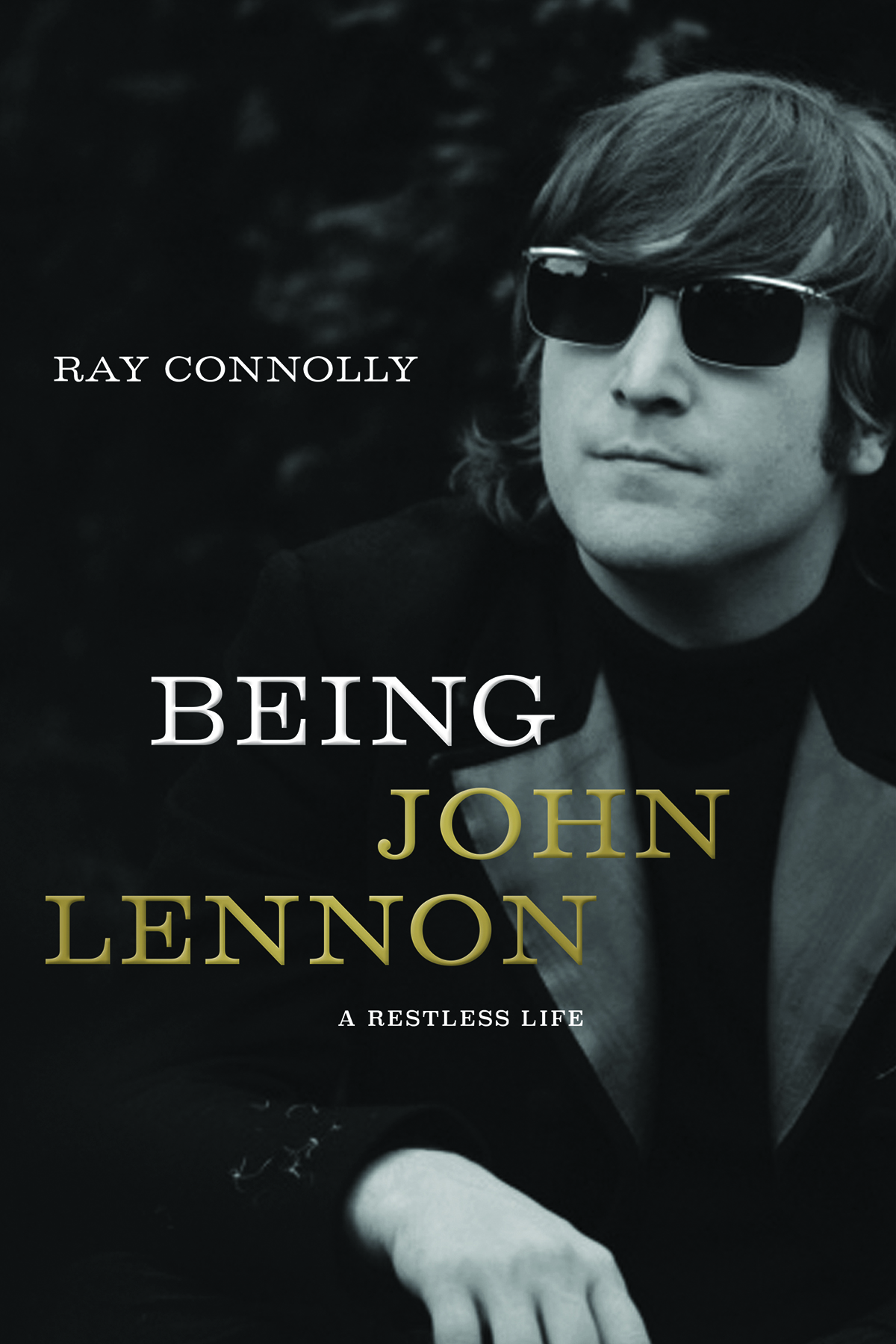

BEING JOHN LENNON

A RESTLESS LIFE

RAY CONNOLLY

For Plum

CONTENTS

On the afternoon of Monday, 8 December 1980, I got a call in London from Yoko Ono, wanting to know why I wasnt in New York. We thought you were coming over, she said. The BBC has been here this weekend. My reply was that when, a few weeks earlier, Id suggested going to interview her and John although, in truth, Id mainly wanted to talk to John shed put me off by saying, The time isnt right. I didnt know whether that meant that her readings of the numbers werent good, because I knew that Yoko was into Numerology, or that there was some other reason. But now with Double Fantasy, the first John Lennon album in five years, in the shops, apparently the time was right, and Yoko was insisting I go to New York immediately. The sooner the better, she urged.

So, I telephoned my editor at the Sunday Times, the newspaper for which I was doing some freelance writing at the time, and a ticket was booked for me on an early flight to New York the following morning. That night, as I played Double Fantasy and reread the lyrics, I was full of anticipation. Id known John since 1967 when Id been reporting on the Beatles as theyd filmed the Magical Mystery Tour in the west of England. After that, having been accepted into the Beatles coterie, Id then watched John work at Londons Abbey Road recording studios, been with him at the Beatles Apple office in London and interviewed him several times at his home, Tittenhurst Park, in Berkshire, as well as accompanying him in Canada and then New York.

It was while wed been in Canada just before Christmas in 1969 that hed given me potentially the biggest scoop of my life as a journalist when hed told me that hed left the Beatles, before adding: But dont write it yet. Ill tell you when you can. So, I didnt.

Four months later when newspaper headlines around the world were screaming PAUL McCARTNEY QUITS BEATLES, he was very grumpy. Why didnt you write it when I told you in Canada? he demanded when I phoned him that morning.

You asked me not to, I replied.

Youre the journalist, Connolly, not me, he snapped, angry because, in his eyes, as hed started the Beatles, when in their embryonic form theyd been called the Quarry Men, he thought he should be known as the one who had broken them up as indeed he had.

Sometimes you just couldnt win with John. But that was John, as changeable as the Liverpool weather.

What would he be like when I got to New York the next day, I was thinking that night in 1980 as I packed my Sony cassette player into my bag. Since his last letter to me four years earlier we hadnt been in touch, as Id written a couple of novels and some television plays and hed retreated from the public gaze to, he would say, bring up his second son Sean, and become a house-husband. Id read his recent interviews with Newsweek and Playboy in which hed talked about enjoying domesticity, but I really couldnt see him having done much child rearing or baked much bread, as theyd reported. Possibly hed got flour on his hands once or twice, I thought, but what else had he been doing for the past five years? I hoped I would soon find out.

Before going to bed at around midnight, London time, I called the Lennons home in the Dakota building in Manhattan to let John know the time that I would be arriving in New York the next afternoon. An assistant answered, saying that John and Yoko had gone down to the studio to mix one of Yokos tracks; and that his instructions were to tell me to go straight to the apartment when I got in, that John was looking forward to seeing me again.

I was woken at four thirty in the morning by the phone beside the bed. In the darkness my first thought was that it must be someone calling to tell me that the cab to take me to the airport was on its way. It wasnt. It was a journalist on the Daily Mail apologising for waking me, but hed just been told from the Mails New York office that John Lennon had been shot.

For a second or two I didnt quite follow, and he had to repeat what hed said. Was John badly injured, I asked, when I gathered my thoughts. The man from the Daily Mail didnt know.

Those were pre-twenty-four-hour news days, so, getting up, I went downstairs and tuned the radio in the kitchen to the BBC World Service.

The headline I was now fearing came as the 5 a.m. news headline. John Lennon was dead, murdered outside his home on New Yorks West 72nd Street as he had returned with his wife, Yoko Ono, from the recording studio. He was forty.

Ten years earlier John had told me he was going to have to slow down if he didnt want to drop dead at forty. As wed smiled together at the thought of one day being as old as forty, hed then asked me: Have you written my obituary yet?

I told him I hadnt.

Id love to read it when you do, hed replied.

I cancelled my flight to New York that morning of 9 December 1980.

I had an obituary to write.

John Lennon didnt fit into any neat classification because he never stayed the same John Lennon for very long. He was a labyrinth of contradictions. As a singer, he disliked the sound of his voice so much he would increasingly disguise it on record; as a rock and roll purist, he also came to consider himself an avant-garde artist; and, as a born leader, he would sometimes find himself being very easily led.

By the end of his life he was a bohemian multi-millionaire who still liked to romantically consider himself a working-class hero, although he had been brought up comfortably off in a roomy home in a pleasant and green suburb outside Liverpool. In truth there was never anything working class about him. Not once in his adult life did he have to do any kind of work other than that of being an entertainer or writer.

But it was in his attitude towards the Beatles that he showed his contrariness, and, perhaps, foresight, most fully. Having started and then helped build the group into the most loved musical and cultural ensemble of the twentieth century, he then merrily turned himself into the iconoclast who destroyed them. In so doing he broke hundreds of millions of hearts.

That the Beatles had to break up at all would become a debate among fans that lasted for decades, but, viewed in retrospect, it was probably the best thing that could have happened to them. By killing them at or near their peak, John was, albeit unknowingly, preserving them, freezing them in time before their music began to be received with a lessening of enthusiasm, as would inevitably have happened had they stayed together.