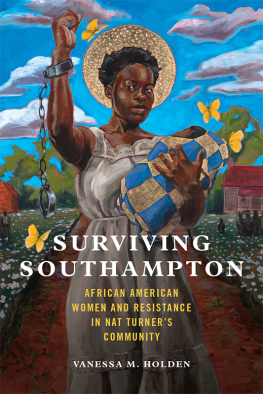

RESEARCH AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research for this book has taken decades and was a journey in itself. It carried me to England, Africa, Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Maine. It has been frustrating and exhilarating. There is no way to adequately thank all who have played a role in this project as it has continued across the years.

In the spring of 1985, I began my search for the Jack Gouldin plantation. I wasn't sure if the house remained, but I thought I could locate the land. I met with one of Jack Gouldin's great-grandsons, Worth Wirt Gouldin of Bealton, Virginia, who provided directions to the house. His instructions were a bit vague, but he said that behind the house there was a cemetery with his great-grandfather's unmarked gravestone. I was energized by the anticipation of finding the plantation and drove through Fredericksburg, out the Tidewater Trail, and toward Skinker's Neck. Somehow, this area had escaped the encroaching sprawl of modern living. I found myself in a morass of back roads and turned on a narrow tree-lined lane, two large fields spread out on either side. I believed I had lost the trail but then saw a house in the distancenot the Tara I had envisioned, but a lonely vestige, sad, in need of repair, painted blue. I was not prepared for the blue color. In my mind, I heard Daisy's voice describing the big white house: with four porches, big wide steps leading to a twelve-foot hallwaya mansion! There was only a remnant of one porch and no wide steps. Two windows were open on the second floor above the door, and staging stood over the entrance, suggesting that some sort of renovation was taking place. But there was no evidence of anyone on the premises and no other houses in view.

Jack Gouldin's house, Port Royal, Virginia, 1985. Courtesy of the Vermont Folklife Center, Middlebury, Vermont, photograph by Jane Beck.

I circled the structure on foot and took photographs. There was no overgrown graveyard; in fact, the ground was clear around the house with woods beyond. Perhaps that was where the graveyard had been, but I did not know where to start a search for it. I learned later that it had been bulldozed. An old barn or shed stood nearby that looked to my untrained eye like an antebellum structure. I fantasized that it might have been the wheat barn where the rafter killed Robert. I was awed by the possibility that this could be where Alec spent his first years. I was uncertain and did not trust that I really had located the plantation. I left wondering how I was going to find answers.

It was two decades later, long after Daisy's death, that I was able to verify that indeed this was Jack Gouldin's house. On my second visit in the spring of 2005, I was with two other people: Gary Stanton (historic preservation professor at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg and a friend and colleague who has helped me at every turn in this project) and Andy Kolovos (loyal friend and archivist at the Vermont Folklife Center). We saw a sign for Hay Mount, which triggered a memoryI recalled reading in the Fredericksburg Ledger, when looking through newspapers at the Central Rappahannock Public Library, that Frank Gouldin's young daughter, Mary Alice, had died at Hay's Mount in 1868.

As the road curved left, I spotted the house across a vast field. It was painted mustard yellow, and the two large trees standing before it on my previous visit were gone. I was almost certain from their appearance in the photographs I had taken twenty years earlier that these were balm of Gilead trees.that they were the same. I wanted to confirm this physical link between Alec and the plantation, if indeed it was the Gouldin plantation.

We came upon a man burning brush, and I was determined to put my questions to rest. The man was George Fisher, the son of the former owner, and he was most congenial. He said the new owner, John Clark, was in the house and would be glad to talk with us. John Clark turned out to be an innovative developer with an evangelist's zeal for his environmentally conscious urban design of four thousand homes, with schools and churches, planned for the land formerly owned by Jack Gouldin. I was still marveling that the landscape had remained relatively unchanged for 150 years, and that Alec would still recognize it. I put all thoughts of the planned development out of my mind and reveled in realizing this was the house; this was the plantation. I was here!

John Clark proved to be very welcoming, was more than willing to show us around, and professed interest in the Turner story. Since that visit, I have been in the house a number of times and have explored the surroundings. With ultimate development of the land in view, Clark had contracted to have an archeological survey done and not only knew the location of a number of the slave cabins, but of the plantation slave cemetery as well. Clark showed us the cemetery site, now with little indication of its former use except for a mass of periwinkles peeking through the leaves. I wondered if I was standing on ground that contained the remains of Robert. If I could peel back the years, what would I see? Were we near where the preacher had raised his arms to the heavens and stopped the coming storm? Only the opaqueness of time stood in my way.

The research and Alec's story had merged. I recognized elements of which Alec had spoken: the great hall and the enclosed staircase leading from it, the room off the hall where Gouldin had kept his trophies, the three staircases that Alec replicated in his own dwelling. I discovered that the Gouldin kitchen had been built over a spring, another detail Alec duplicated. Clark pointed out a section of wall used as a ledger. It was tucked away in a closet on the second floor and preserved with a Plexiglas covering. Under the glass was scrawled the penciled date of 1862 and a listing of items, mostly quilts and blankets. Among them was Father's blanket, provided by the Gouldins for Confederate soldiers camped on the plantation grounds. I realized this would have dated from the winter of 1862 before Alec took flight. He would have seen the soldiers who must have fueled endless conversation about the war in the slave quarters. Those penciled lines linked me to a reality that had existed 140 years before. I felt I was inhabiting Daisy's stories.

I was fortunate to meet Ken Clark, base historian at Fort A. P. Hill, who showed me an area that had been important to the Gouldins, including the Bethesda Baptist Church, Liberty Baptist Church, and Rappahannock Academy. Cleo Coleman, a native of Caroline County, shared her wealth of knowledge and personal family stories and has proved to be a tremendous resource. I have Marie Morton to thank for making available her work on the histories of the different parcels of land that make up Fort A. P. Hill and for her explanations as to how different farms amalgamated into the Gouldin property related to one another.

I was not so fortunate in locating the vessel that carried Daisy's great-grandmother from London to Africa. I began with Daisy's grandfather's name, Berkeley, and looked for its antecedents in England. There was an Earl of Berkeley, but no one in the Earl's line had a daughter who could fit the specifics of the story. Nina Staehle did some initial research for me and introduced me to the workings of the National Archives. I had no ship's name, no owner, no captain, and no date. Daunting, but I thought if I could find ships wrecked on the West African coast between 1790 and 1815, I might be able to identify the vessel. I went through Lloyds List and the Times (London) to find possibilities. One of the first I came up with was the brig