To Anne

Contents

In addition to the relevant facts, winnowed from heaps of raw information, a biography ought to give a sense of what its subject was like to shake hands with or stand next to or drink coffee with. So here, before we burrow into the life and work, is a little vignette I hope will give a taste of John Updike, the flavor of the man as he appeared to me in the late fall of 1993, when I trailed behind him, playing Boswell for a day and a half. We were in Appleton, Wisconsin, at Lawrence University, where Updikes younger son had studied in the eighties. Updike had been invited to give the convocation address, dine at the home of the university president, and talk with students in a writing seminar. It was the sort of well-paid trip Updike made over and over again. He was on display as Americas preeminent man of letters, showing off what he called his public, marketable selfa wonderfully controlled and pleasing performance that revealed, it seemed to me, a good deal about his private, hidden self.

He had barely sat down (we were at a buffet supper at the presidents house, plates balanced on knees, guests in armchairs or perched on footstools) when a well-dressed woman sitting near him asked in a sweet midwestern voice, Mr. Updikedid you write the wonderful story about the man who swims from pool to pool?

I wish I had, he answered at once, his voice honeyed like his interlocutors; that was John Cheever, The Swimmer. He grinned, and contained in that wolfish grinhis small mouth a sharp V in his long, narrow facewas a mixture of pure amusement, malice, and forbearance. Perhaps now that John is dead I could lay claim to some of his stories. The assembled company exhaled with a long, relieved laugh. They were relaxing, surrendering to his charm.

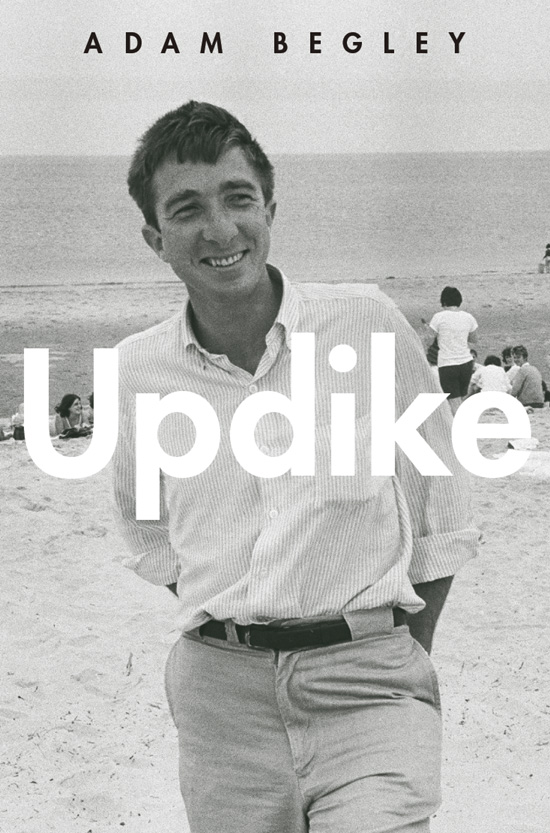

Encouraged, the same woman spoke up again, asking if Mr. Updike, so famously prolific, was slowing down, thinking of retirement. Again, the response was instant: Do you think I should? At sixty-one? His tousled hair was nearly white, his eyebrows scruffy like an old mans. A network of fine wrinkles surrounded his eyesbut the eyes themselves were bright and lively (he had a bona fide twinkle in his eye, said Jane Smiley, maybe the only person Ive ever known to really have such a thing). He was tall and lanky but not remotely feeble or doddery. On the contrary, he exuded a vigorous self-confidence, an almost palpable centeredness. His voice, still sweet, had taken on a flirty, comically submissive edge, as if the advice of this midwestern Cheever fan could hasten his retirement and shape the end of an illustrious literary career. I have been tidying up, he offered, along with another friendly, wickedly acute grin.

That moment of teasing social agility sparked my suspicion that the playfully mischievous, dazzlingly clever John Updike was a potentially dangerous individual, and that a gamut of conflicting emotions, not all of them kindly, were hidden behind the screen of his public persona. I think it was the hint of danger, subliminally communicated to the clutch of listeners in the presidents blandly elegant living room, that made his performance in the role of celebrated author so appealing. Yes, he was a professional writer being professionally engaging, but he was also signalinghow? with that clichd twinkle?that his good behavior, his forbearance, had its limits.

At the time, Id read only a few dozen Updike stories and a couple of the novels; when I finally read his memoirs, I found this apposite passage about an earlier trip to a midwestern university:

I read and talked into the microphone and was gracious to the local rich, the English faculty and the college president, and the students with their clear skin and shining eyes and inviting innocence, like a blank surface one wishes to scribble obscenities on.

Suspicion confirmed. Of course there was an undercurrent of aggression in all that expertly deployed charm, a razor edge to his ostensibly gentle wit. In one of the dazzling self-interviews with his alter ego Henry Bech, he lamented his own eagerness to please and ridiculed the whole notion that a writer should be nice: [A]s Norman Mailer pointed out decades ago, and Philip Roth not long afterwards, niceness is the enemy. Every soft stroke from society is like the pfft of an aerosol can as it eats up a few more atoms of our brains delicate ozone, and furthers our personal cretinization. A nice, happy author? No, thanks. I found I liked him all the more.

Its possible, I suppose, that I was programmed to like him. My father and he were classmates in college, both of them majoring in English, and for a while after graduation, when my parents were living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Updike and his first wife had moved to Ipswich, less than an hour away, the two couples were friendly. Fifty years later, when Updike died unexpectedly (very few people knew that he was ill, let alone dying), my father sent me an e-mail version of an anecdote Id heard before:

One day for some reason John came to see us alone, in the early afternoon. We were in our living room, which was flooded by the afternoon sun. You were in your Easy Chair, a contraption in universal use then among advanced couples, which allowed the pre-toddler to recline rather as though he were in a barbers chair having his hair shampooed. One of Johns less known talents was his skill as a juggler. He took three oranges from a bowl on the coffee table and began to juggle for you, and you began to laugh. Astonishing belly laughter.

According to this family legend, Updike was the first person to make me laugh. Part of me believed it, and believed it was a natural consequence of this early imprint that I found him congenial when I met him as an adult, the baby in the Easy Chair having grown up to be a literary journalist. Whenever we spoke (which wasnt oftenall told perhaps a dozen phone calls and two extended face-to-face interviews), I was amazed and delighted by his gracious, professional manner, and by the sly undercutting of his public, marketable self. He wanted to let you know that he was perfectly aware of the falsity of the situation, and perfectly prepared to be amused by it, for the moment. He wanted to let you know that his real self was elsewhere.

This wasnt just a targeted trick, like juggling for a baby, deployed for the benefit of an admiring journalist; old friends and colleagues noticed it, too. John could be funny and very friendly, said his Harvard friend Michael Arlen, but you always felt that this was just a parallel universe we were occupying for the momentthe real universe was back at his desk. Roger Angell, Updikes New Yorker fiction editor for more than thirty years, observed how, near the end of each visit to the magazines offices, he somehow withdrew a little, growing more private and less visible even before he turned away. Angell called it the fadeaway and thought it had to do with being temporarily exiled from writing: the spacious writing part of him was held to one side when not engaged, kept ready for its engrossing daily stint back home. He was there but not therejust as he was kind but subversive, and charming but dangerous.

Another confusion: Updike thought of himself, or wanted to think of himself, as a pretty average person. So he said at age forty-nine. But since childhood hed been assured that he was exceptional, brighter and more talented than the rest. And surely he was. A drumroll of honors, prizes, and awards accompanies the very long list of his published bookssixty-odd in fifty-one years! The list and the accolades confirm that he was indeed extraordinary. His most obsessive fan, Nicholson Baker, whose U and I is easily the strangest homage he ever received, declared unreservedly that Updike was a genius (but rightly conceded that the word has no useful meaning). My ideas about this question are borrowed from Lionel Trilling, who wrote about George Orwell, He was not a genius, and this is one of the remarkable things about him. Trilling thought Orwell stood for the virtue of not being a genius, of fronting the world with nothing more than ones simple, direct, undeceived intelligence, and a respect for the powers one does have, and the work one undertakes to do. Updike once declared that his epitaph should be Here lies a small-town boy who tried to make the most out of what he had, who made up with diligence what he might have lacked in brilliance.