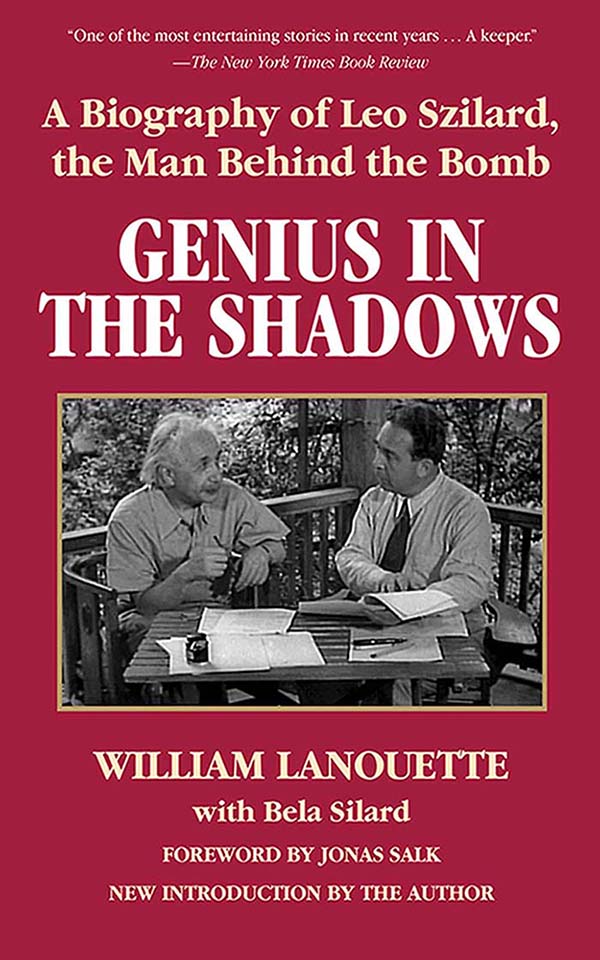

GENIUS IN

THE SHADOWS

A Biography of Leo Szilard,

the Man Behind the Bomb

W ILLIAM L ANOUETTE

WITH B ELA S ILARD

Foreword by J ONAS S ALK

Copyright 2013 by William Lanouette

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-023-5

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-62636-378-6

Printed in the United States of America

To my parents

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

T. S. E LIOT ,

The Hollow Men

Contents

Illustrations

Leo Szilard at about age five

Louis Szilard, Leos father

Leo Szilards mother with one-year-old Leo

Bela, Leo, and Rose Szilard

The Vidor Villa, where Leo grew up

Leo Szilard in 1916

A Vidor family holiday in Austria

Cooling the Passions, a humorous pose with relatives and friends Leo Szilards 1919 passport photo

Leo Szilard at a field artillery barracks during World War I

Alice Eppinger

Leo Szilard in the 1920s

Leo Szilard with friends at Lecco, Lake Como, Italy, in 1926

Gertrud (Trude) Weiss

Leo Szilard in England in 1936

Leo Szilard and Ernest O. Lawrence at the 1935 American Physical Society meeting in Washington, DC

Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard in a 1946 March of Time film

The creators of the worlds first nuclear chain reaction pose in December 1946

Eugene Wagner and Leo Szilard in Manhattan in the late 1930s

Leo Szilard testifying before the House Military Affairs Committee in October 1945

Members at the Carnegie Institutions annual theoretical physics conference, spring 1946

Leo Szilard in Wading River State Park, June 1948

Leo Szilard at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founders of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists at the Institute for Leo Szilard with Cyrus Eaton at the first Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs in July 1957

Leo Szilard in the Rocky Mountain National Park in the 1950s

Aaron Novick and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard as sketched by Eva Zeisel

Leo Szilard on the Atlantic City boardwalk, March 1948

Leo Szilard with Jonas Salk

Leo Szilard with Matthew Meselson and Leslie Orgel Leo Szilard with Trude at Memorial Hospital, 1960

Leo Szilard at a Pugwash conference banquet in Moscow, November 1960 Szilard with Inge Feltrinelli in Italy Jacques Monod and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard at the Dupont Plaza Hotel in Washington, DC

Caricature of Leo Szilard in a bathtub by Robert Grossman

Leo Szilard reading to a young girl

Henry Kissinger, Leo Szilard, and Eugene Rabinowitch

Eleanor Roosevelt and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard with Michael Straight

Leo Szilard with Francis Crick and Jonas Salk, spring 1964

Szilard speaking at a Salk Institute seminar, February 1964

Leo Szilards ashes at Kerepsi Cemetery in Budapest

Leo Szilards tombstone at Lake View Cemetery in Itaca, New York

Introduction

to the 2013 Edition

Nearly half a century after Leo Szilards death, and two decades after this biographys first edition, Leo Szilard remains, by and large, an obscure figure for the public. Not so for historians and many scientists, however; his ideas and spirit still offer us helpful scientific, political, and moral perspectivesand a few surprises.

In Szilards political satire The Voice of the Dolphins, he imitated Edward Bellamys utopian science-fiction novel Looking Backward by predicting correctly in 1961 how the US-Soviet nuclear arms race would wind down in the late 1980s. Nuclear weapons still imperil humanity, but now in newly bizarre ways that defy the Cold Wars deadly logic. Szilard would applaud one Cold War outcome asall too slowlynuclear arsenals are being put to better use. In debates during the 1960s about whether to test nuclear weapons, Szilard joked that you should test them! Test them all! Every last one! That never happened, but by 2012, the weapons-grade uranium equivalent of 18,000 Russian warheads had been recycled into fuel for US nuclear power plants by the Megatons to Megawatts Program. And he would still urge nuclear powers to test them all!

On the fiftieth anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1995, scientists who strived to control nuclear weapons were honored when the Nobel Peace Prize went to the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs and its founding leader Joseph Rotblat. Szilard had helped start Pugwash in 1957, then fostered its approach of candid, private intellectual discourse among scientists, insinuating, he said, the sweet voice of reason to the nuclear arms race. He was one of its most ardent members.

But in 1995 a new history revealed how Szilards influence had spread unforeseen but decisive resultsnot by intellectual discourse but by humor. With tongue in cheek but still in moral earnest, Szilard had unknowingly inspired the Russian H-bomb designer Andrei Sakharov to become a champion for arms control and human rights. This tale begins in 1947, when Szilard wrote the political satire My Trial as a War Criminal to dramatize how scientists are responsible for their creations: in his case, the A-bomb. Historian Richard Rhodes wrote in Dark Sun, his 1995 history of the H-bomb, that when Szilards satire was republished in 1961, Sakharov read it in translation and embraced its moral imperative, prompting the heroic political activism that earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975.

Szilards influence was explained by Sakharovs friend and colleague, Viktor Adamsky, who had translated the satire. We were amazed by [Szilards] paradox, Adamsky told Rhodes. You cant get away from the fact that we were developing weapons of mass destruction. We thought it was necessary. Such was our inner conviction. But still the moral aspect of it would not let Andrei Dmitrievich [Sakharov] and some of us live in peace. In this way, Rhodes disclosed, Szilards story delivered a note in a bottle to a secret Soviet laboratory that contributed to Andrei Sakharovs courageous work of protest that helped bring the US-Soviet nuclear arms race to an end.