Hughes - The big sea: an autobiography

Here you can read online Hughes - The big sea: an autobiography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Harlem (New York;N.Y.);New York (State);New York;Harlem, year: 1993, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux;Hill and Wang, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The big sea: an autobiography

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux;Hill and Wang

- Genre:

- Year:1993

- City:Harlem (New York;N.Y.);New York (State);New York;Harlem

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The big sea: an autobiography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The big sea: an autobiography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The big sea: an autobiography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The big sea: an autobiography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

TO

EMERSON AND TOY HARPER

INTRODUCTION

Langston Hughes was for some time a reluctant autobiographer. Although he published The Big Sea (1940) when he was only thirty-eight, he was first asked seriously to write such a work when he was just past twenty-three, in 1925. To help his mentor Carl Van Vechten with his introduction to Hughess first book of poetry, The Weary Blues (1926), Hughes had sent Lhistoire de ma vie, a brief but dazzling essay that set off a brainstorm in Van Vechten. Yes, the publisher Alfred A. Knopf (who was about to bring out Hughess first book of poems) and he completely agreed: Hughes should do an autobiography at once! But Hughes did not like the idea. I hate to think backwards, he explained. It isnt amusing I am still too much enmeshed in the affects of my young life to write clearly about it. I havent escaped into serenity and grown old yet. I wish I could. What moron ever wrote those lines about carry me back to the scenes of my childhood?

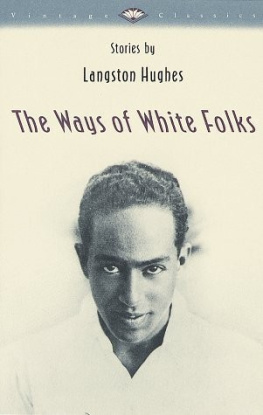

By 1939, when he sat down at last to write his autobiography, he was presumably no longer so enmeshed in the affects of my young life that he could not write clearly about it. Moreover, he was no longer so young. After The Weary Blues had come another volume of verse, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927); then a novel, Not Without Laughter (1930); a collection of stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934); a collection of radical verse, A New Song (1938); and a long-running Broadway play, Mulatto (1935), in addition to other produced plays and lesser publications. More important, by this time the adult mask so carefully constructed to conceal the affects of my young life was firmly in place. In 1939, Langston Hughes was internationally known as a leftist radical, a proudly racial poet, and a daring world traveler who had spent a year in the U.S.S.R., then come home via China and Japan.

Nevertheless, some friends saw a puzzle in his personality. At one level, Langston was the ever-smiling, often-laughing boon companion; at another, he was unfathomable. One fictional portrait, drawn in the nineteen-twenties by the black novelist Wallace Thurman, had him as the most close-mouthed and cagey individual the narrator had ever encountered when it came to personal matters. He fended off every attempt to probe his inner self and did this with such an unconscious and nave air that the prober soon came to one of two conclusions: Either [Hughes] had no depth whatsoever, or else he was too deep for plumbing by ordinary mortals. The German intellectual Arthur Koestler, who had roamed with him in Central Asia during several weeks in 1932, would report that behind the warm smile of his dark eyes there was a grave dignity, and a polite reserve which communicated itself at once. He was very likable and easy to get on with, but at the same time one felt an impenetrable, elusive remoteness which warded off all undue familiarity.

On the surface, the purpose of autobiography is to reveal. On the other hand, it is a commonplace that significant autobiographies begin under unconscious orders from the autobiographer. What were Hughess orders, insofar as we can guess them? Two, perhaps, were more important than all others. First, Hughes, who depended almost desperately on the smiling surface he offered to the world, had to preserve that face even as he expressed, as an artist, some intimation of psychological depth that could come only from the recitation of varied and trying experiencesin short, from the revelation of conflict and unhappiness. Second, and more telling, Hughes, who for certain intimate reasons craved the affection and regard of blacks to an extent shared by perhaps no other important black writer, had to compose a book that would speak not only to whiteswho published and bought books, who made books possiblebut also to blacks. And yet the message of a black writer to whites and the message from the same writer to blacks are often not only different but contradictory.

His loving sense of a black audience led to problems from the start. When Blanche Knopf read the first draft of The Big Sea, she found tedious the long Harlem Renaissance section that comprises the second half of the book. It was too full of Carl [Van Vechten], [Wallace] Thurman, [Jean] Toomer, and so on, until it became a sort of Harlem Cavalcade, which is wrong. In response, he vigorously defended the details of Harlem life as the background against which I moved and developed as a writer, and from which much of the material of my stories and poems came. No doubt, some small portions of it may have vital meaning only to my own people, but these portions would add to the final integrity and truth of the work as a whole: I am trying to write a truthful and honest book. Black readers would certainly give me a razzing if I wrote only about sailors, Paris night clubs, etc., and didnt put something cultural in the bookalthough the material is not there for that reason, but because it was a part of my life. And the fault lies in the writing if I have not made it live.

Largely at the insistence of Van Vechten, almost all the cuts were restored. Langston was the last historian of that period who knows anything about it, Van Vechten declared in urging Hughes to expand rather than trim the sectionwhich is now generally recognized as the finest firsthand account of the Harlem Renaissance in existence. But Hughess attempt to reach the black reader went further than such sections.

That The Big Sea is a tour de force of subterfuge is strongly suggested by the conflicting contemporary reviews of the book. Most alertly, The New York Times Book Review saw both sidesthe work was both sensitive and poised, candid and reticent, realistic and embittered. Where the Times saw substantial bitterness, however, the New York Sun noted that Hughes does not allow much bitterness to creep in; and another reviewer urged whites to read it because it is true and honest and not bitter. Whereas in The Nation, Oswald Garrison Villard spoke of Hughess absolute intellectual honesty and frankness, elsewhere Alain Locke lamented that Hughes had glossed over too many important matters. The radical Ella Winter found him too gentle with us white folks. Ralph Ellison, then a Marxist, complained that too much attention is apt to be given to the aesthetic aspects of experience at the expense of its deeper meanings; he further questioned whether the style was appropriate to the autobiography of a Negro writer of Hughess importance. Another radical was shocked to notice not a single mention of a radical publication youve written for or a single radical you have met or who has meant anything to you. In The New Republic, Richard Wright praised Hughes as a cultural ambassador who had carried on a manly tradition in literature when other black writers have gone to sleep at their posts. In calling Hughes a cultural ambassador, however, Wright invited memory of a passage in his most important essay, Blueprint for Negro Writing, where he had scorned past black writing in general as the prim and decorous ambassadors, the artistic ambassadors who went a-begging to white America in the knee-pants of servility.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The big sea: an autobiography»

Look at similar books to The big sea: an autobiography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The big sea: an autobiography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.