Publication of this book was assisted by

the American Council of Learned Societies

under a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

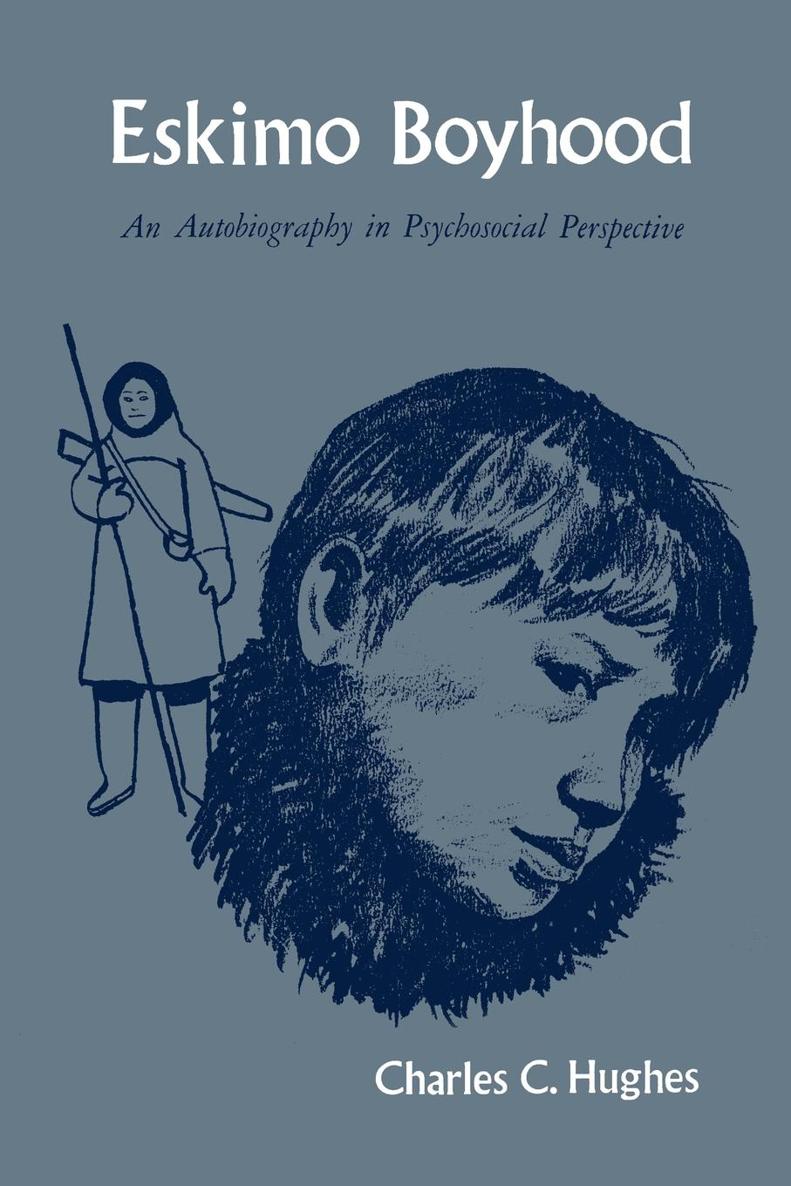

Illustrated by Dirk Gringhuis

ISBN: 978-0-8131-5316-2

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80465

Copyright 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky

A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency

serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky,

Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and

Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506

When we got close, those who had been at home were coming down the hill to the beach. I saw my cousins running and rolling down like I did when the boat came in from hunting. I jumped out of the boat, feeling very proud. I had lots to tell my folks while we unloaded the boat. My uncle said that now he would have one more crew member, because I had not been afraidnot even a little bit. I felt a little funny, and I was glad he hadnt seen my fright. That meant I was a real man and a real hunter from then on. The young Eskimo man who with these words tells of his first hunting trip in a skin boat had been but six years old at the time. Six years old; but for him the beginning of manhood, because hunting was the life of the Eskimo man.

Later, many times, coming back with seal carcasses or walrus flesh in the boat, he was to relive the excitement and sense of mastery of that first trip. But just as often he was to experience another lesson as wellthe other coinage of a mature self-reliancewhen he returned with nothing for his days work, tired, numbed from cold, and edgy with the disappointments so common in the life of an Eskimo hunter: perhaps a sea barren of animals, perhaps the erring of rifle shot, the sudden movements of ice floes shielding a carcass from the harpoon throw, or the capricious closing in of weather that changed the world to wind and snow. Throughout life, as backdrop to the affairs of men, he was always to contest with an unrelenting nature that threatened not only his survival but also his sense of well-being and hope for fulfillment.

The purpose of this book is to portray the first steps taken into that life by a young Eskimo, Nathan Kakianak,* who lived it and who here recounts it. With only slight editorial changes, the portrayal is principally in the form of an autobiography written by a young man in his early twenties, who tells of his life up to the middle years of his youth. The life story was written (in English) at my request and mostly under conditions conducive to recalling nostalgic personal memories, for much of the first part was set down while he was hospitalized with an advanced case of tuberculosis. The autobiography is presented almost in its entirety; only a few sections have been deleted to shorten the document and minor editorial revisions and grammatical alterations made for easier reading. It is important, however, to reaffirm the essential authenticity of the phraseology and vocabulary used, for Nathan had only a fourth-grade education, and that obtained very sporadically.

How accurate is his detailed recollection of events and conversations? I do not know for certain, but for one thing, ethnographers working with the Eskimos (and many other hunting peoples) have often commented on their unusual capabilities for remembering minute detail. My position regarding the following document is that for the purposes intended here, the matter of minute accuracy of detail (such as specific conversations) is of relative unimportance, since my interests are not so much in the exact way Nathan says something, but rather more in what events and associations of events he brings forth. In any case, it can be asserted on the basis of outsiders studies of this group that whether or not all the situations and events mentioned in the autobiography actually took place as described, they are at least common enough types of events in the cultural life of these people that they could have taken place in his life (e.g., see Hughes, 1960).

However that may be, the life recounted hereindeed, any lifecan teach something about other lives as well; and following the life history I attempt to indicate some of the ways in which this life exemplifies more widespread human personality processes in the midst of highly unique cultural, social, and geographic conditions. Such an attempt is, of course, a venture into controversy; for viewed in a behavioral science framework an autobiographical document is suspect from several points of view. First is its representativeness or typicality for a wider range of subjectswhether in terms of age, sex, socioeconomic conditions, or sheer involvement in particular historical eventseven beyond the fact that the single document is only one case from a larger population of instances.* Then, too, is its validityhow accurately and honestly does the subject reveal himself to the anonymous reader? How much does he distort, suppress, expand, and exaggerate? To what extent does selective recall influence the character of the chain of associations and memories which constitute the structure of the recollected life?

To such questions I have no final answers, only the judgment that in view of all available evidence what follows is not the record of a highly deviant life career in this society. But such questions as those above, even if they cannot be fully answered, do raise further issues on which it is necessary to comment: why this life history? What is its presentation intended to accomplish? Why this single case?

In my view there are several reasons to publish it simply as it is. For one thing, it is a statement that absorbingly conveys much of the inner meaning of another culture, another way of life, and the personal quandaries and struggles of a growing boy to establish himself in that life. As such, the document makes perhaps a useful contribution to the study of lives, comparatively an underdeveloped area in the behavioral sciences, skilled though these sciences be in the analysis of fragments of behavior abstracted from the evolving dynamic and creative structures which are personalities. Personal documents, if they serve no other purpose, provide a check on theoretical assumptions that would make man an automaton, a passive actualizer of a comprehensive sociocultural programming (see Wrong, 1961). Paradoxically, while underscoring on the one hand the enormous molding influence of cultural circumstances, personal documents at the same time provide cogent evidence for mans ability to have some influence in constructing his destiny, in shaping his inevitabilities.