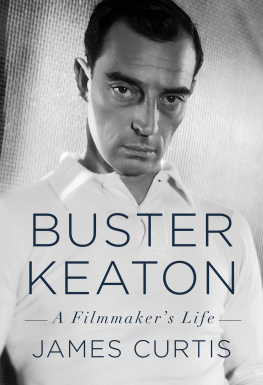

I am sitting in an auditorium, watching a woman rip the lining out of an expensive fur felt fedora and dunk it into a bucket of water. I am taking notes on this; the forty-odd people around me are taking notes on this. We have come from London, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, New Orleans, Cottage Grove. We have been here since eight-thirty this morning. It is a Buster Keaton convention. Were learning to make a porkpie hat.

The people around me are warm, gracious, and as they will be the first to admit unusual. They are all members of the Damfinos, the International Buster Keaton Society, some 700 members strong. Theyre the kind of people who know Busters hat size (6), people who sit around talking about projection speeds, people who have been inside the Italian Villa (Busters former Hollywood mansion, not open to the public), people who recall which prints of which eighty-year -old movies are missing which scenes, people who get married in Keaton-specific locations, people with Buster tattoos, people who know whether Roscoe Fatty Arbuckles suspenders buttoned on the inside or outside of his pants, people who will take five trains and brave two hurricanes to get to the convention, passionate people, people who take things personally. I am writing a book on Buster Keaton, and they make me nervous.

At the convention, I fail the trivia quiz miserably. They still let me attend the banquet, where we dine on Busters favorite foods. There is an auction, and to the highest bidder go out-of-print books, a Keaton life mask, a portrait of Buster made out of 15,000 strung beads, original postcards, rare films, and the like. Later, I gain admittance to the costumed speakeasy, where someone shows up with Roscoe Arbuckles actual scrapbook, full of never-before-seen clippings and photos; a huddle forms and lasts through the wee hours.

Why were in Muskegon

It has nothing to do with nostalgia, or a discomfort with living in our own time, or a fascination with the esoteric. Its because of the movies. Keatons films are witty, beautiful, unsentimental, moving, and most of all funny. As he scrambles onscreen, objects come to peculiar (yet pragmatic) ends, driven in an instant to the curious brink of comedic perfection: in his hurly-burly world, a car might serve as a sailboat, a violin could double as a paddle, and Keaton himself can turn into a monkey. Even when striking a minor key, a Keaton flick cant help but betray an excitement, an underpinning joy the 1920s were a heady time, film was a new art, and society was in a terrible hurry to become something else. So houses fall, cars careen out of control, locomotives plunge into rivers everything is on the verge of collapse or collision and Keaton is there shooting it all, flinging down films from the high-wire act of modern life. The forces that stand between a man and love, happiness, and success are tremendous and well organized. Its all you can do but laugh.

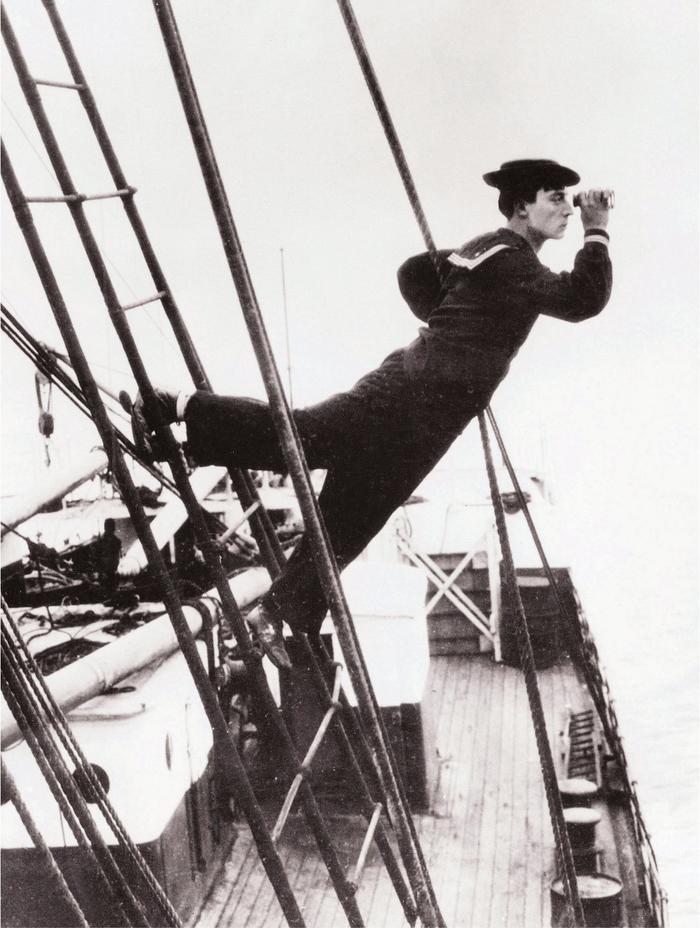

And laugh hard. Keaton was a master of the streamlined gag. His precision, geometry, and grace register in your gut long before your mind can wrap itself around what hes doing. He once said, A good comedy story can be written on a penny postcard, and the remark carries more than a whiff of Keatons signature self-effacement. But he was more than a genius. He was a prodigious acrobat and brilliant writer, gagman, director, and editor a 56 auteur masquerading as a clown.

And so people go to Muskegon, and to theaters across the world, because Keatons work feels fiercely relevant. While his contemporaries wrote in strokes that today seem terribly broad, Keaton was a man who prized subtlety and understood meaning in the flick of an eye, a momentary hesitation, a shift in weight, a motion half-begun. He underscored the big-screen spectacle (cyclones, avalanches, Keaton was also the more honest storyteller his films might be touching, but not in the determinedly sentimental mode of Chaplin. Keaton eschewed weepy close-ups, and his stories often dont end happily, but instead with a final nod to bitterness, dejection, or death an unexpected final twist, the kind of flawless gesture that explodes the closure it purports to bring. Luckily for us, Keatons little fellow had a habit of keeping his chin up, despite the fact that it seemed to attract punch after undeserved punch.

Why a book?

This book is merely a fans notes. It is meant to celebrate an unbelievably fertile time in American cinema that was the result of an extraordinary man working under extraordinary circumstances with absolute artistic freedom, in the fluidity of the silent medium, infused with the bravado of the machine age, supported by a crack team, fresh in the athletic vigor of his youth.

And for that, I will attempt to avoid the pitfall of the Stone Face. It was Keatons greatest trademark, but over the years it unfortunately has served as an interpretative Rorschach for the thesis-laden biographer , an ambiguous nail on which to hang even the most ludicrous interpretation. Keatons blank affect has led many critics to fixate on his stoicism, to make him over as a sort of existential hero, or weep for him as a bruised and battered soul. Making matters worse, biographers have gotten bogged down in a sort of psychoanalytical quagmire marking with relish each absent father that appears in his work, each instance of paternal abuse. Surely his fathers alcoholism played a part in his own; certainly casting dear old Dad as a bruising monster is an act of aggression. But these approaches miss the joy in the films theyre funny! and fail to recognize how a man can hold dignity in his face and still say it all with his eyes.

So with thanks to the Damfinos for their hospitality (and with apologies for any errors Im still working on the quiz), I submit this book to the generation just discovering Keaton, who find him not only at the art house, but in the video store people who can partake in the relatively new pleasure of rewinding the scenes, dissecting the impossible pratfalls, and wondering over and over to themselves, how did he do that?

Notes

A good comedy story ; Blesh, p. 133.

LAT, October 29, 1995.

Keaton & Samuels, p. 126.

Our hero came from Nowhere he wasnt going Anywhere and got kicked off Somewhere.

The High Sign (1921)

Friday, October 4, 1895. In Egypt, the Nile runs unusually high; Great Britain is experiencing uncommonly cold weather after a period of uncommon warmth; somewhere in Canada, a railroad superintendent on the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Line mysteriously disappears between stops; four men fall off a rope bridge some forty feet into a riverbed in Sing Sing, New York; two Massachusetts balloonatics are stranded aloft when their guide suddenly collapses. And in Piqua, Kansas, population somewhere around 200, Joseph Frank Keaton is born. His proud parents Myra, a 411 ninety-pound whiskey-drinking bull-fiddle player, and Joe, a brawling self-promoter with a prodigious high kick, are traveling the vaudeville circuit with the Mohawk Indian Medicine Show. When the show moves on, so does Joe, leaving his wife and child to catch up with him some two weeks later. Throughout his life, Joe Jr. would claim that Piqua was blown off the map shortly thereafter by a cyclone a fictitious yet fitting bit of theatrical kinetics for the boy who would weather tremendous storms, both real and imaginary, as comedys Great Stone Face.

Myra and Joe were star-crossed lovers from the start. She was the Iowa-born daughter of Frank L. Cutler, owner of the Cutler Comedy Company, one of the Old Wests many roving medicine shows. A traveling nineteenth-century infomercial of sorts, the medicine show was a marriage of entertainment and commerce, offering the public free outdoor variety acts while deriving revenue from the boozy tonic it aggressively hawked. The son of a miller, Joe Keaton hailed from a sober line of Indiana Quakers, but as his self-styled legend has it he lit out