Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase

A Biography

Marion Meade

For Ashley Elizabeth Sprague

FADE IN

The blare of automobile horns rumbles through the streets of Times Square. On an unseasonably cold March day in 1917, a young man, all by himself, is pushing through the noontime traffic. He is twenty-one years old but looks younger, with a solemn, pretty-boy face and a shock of straight dark hair.

When he hears his name called, his head snaps around to see a man stepping toward him, a comic he knows from vaudeville. Looking surprisingly prosperous, the vaudevillian reports that he retired from the stage to manage a movie studio. "You've never been in the movies, have you?" he says.

Absolutely not. His family disdains motion pictures. In fact, a lucky break has just won him a role in a Broadway musical comedy. In his mind there is no comparison whatsoever between a Shubert musical and second-rate enterprises like movies.

But when he is invited to see for himself how a comedy is made, he agrees to go along.

Walking east on Forty-eighth Street, they cross Fifth Avenue, pass under the Third Avenue El, and stop just short of the East River at an old warehouse. At Colony Studio, observing the action on a country-store set, the young man gets his first glimpse of filmmaking. He watches all afternoon, completely transfixed, not by the story, not by its star, Roscoe Arbuckle, but by the camera. How does it work? What drives the film through the camera? How are the pieces of celluloid assembled?

By evening he is still there. He's even played a customer who buys a bucketful of molasses. As the crew prepares to leave, he turns to Arbuckle. May he borrow one of the cameras?

In his room that night, he dismantles the Bell & Howell. All the spools and discs and spindles are spread out before him. After his curiosity is completely satisfied, he reassembles the camera. The next day he quits his job in The Passing Show of 1917.

Nineteen ninety-five celebrates the hundredth anniversary of Joseph Frank Keaton's birth. Born into a family of touring medicine-show performers, the baby fell down a flight of stairs and became known as Buster. The nickname stuck to him for the rest of his life.

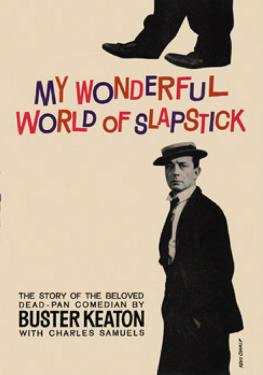

In movies, Keaton's universe keeps collapsing: houses crash on him, rocks chase him down hills, boats sink beneath his feet. Fearless Buster in his pancake hat copes with havoc, hilariously. His private life was also full of endless indignities: the anguish of a rough, battering father and an ice-cold mother, his loss of an education, alcoholism, problems with the Hollywood system, profound depression, broken marriages. But Keaton was a fighter. He despaired, then continued on. In the end he triumphed through courage, perseverance, and obsession with work.

One of the true geniuses of American cinema, Keaton seems to be untouched by time. There was no one like him. He was the complete filmmaker, who conceived, wrote, directed, edited, and starred in ten silent feature films and nineteen short comedies. His masterpiece, The General, continues to be praised as one of the greatest films of all time.

He was the best comedy director in the business, a director's director. Luis Bunuel was a great fan. Sergei Eisensteinand Woody Allen and Leni Riefenstahl, Billy Wilder and Martin Scorsesefound him delicious. Today he is primarily honored as a legendary independent filmmaker. But the full scope of his artistry is breathtaking. He was a superb athlete who created incomparable physical comedy in such films as Cops and The Navigator. He was a magnificent actor whose impassive facial expressionhe was called Deadpan and Stonefaceis misleading. He didn't need a smile to convey his thoughts or feelings.

Keaton became the lyric poet of silent films. His stories are about the special worlds of newsreel cameramen, Civil War railroad engineers, butterfly collectors, Roman charioteers, movie projectionists, gallant cowboys, prizefighters, and debonair playboys. They are also about himself, with slivers of Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton embedded in every character he played.

In Sherlock Jr. Buster walks down the aisle of a theater and enters the movie screen. In The Playhouse, nine Busters perform together. But that's not all. By multiple exposures, he becomes every member of the orchestra and the audience. Offscreen, he was not an ordinary person either. Practically his entire life was spent in the limelight. At the age of five he made a sensational debut as a vaudeville comic. His stardom lasted a lifetime. For Buster, celebrity was never a goal, it was a childhood accident.

By his death on February 1, 1966, enthusiastic film aficionados had began calling him a genius. Such reverence made him terrifically uncomfortable: "No man can be a genius in slapshoes and flat hat." He preferred to be remembered as a performer whose career lasted almost seven decades. "I work more than Doris Day," he joked. Hollywood Boulevard's Walk of Fame honors him as a two-star celebrity, for his work in movies and television.

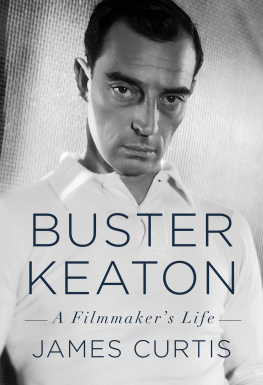

This book focuses on Buster's personal life. In recent years several fine books about his films have been published, so I saw no reason to plow the same field. By exploring the various events of his private life, my aim is to reveal a more detailed picture of the artist, which perhaps will further illuminate his art.

Keaton's legacy is twofold: as master of the sight gag he was one of the most sublime film comedians of them all; and as a master film director, his work behind the camera cannot be rivaled for its sheer visual brilliance. By exploring the camera's possibilities, he helped advance cinema into a sophisticated art form.

ONE

CHEROKEE STRIP

Summer lingers like death on the prairie. It had not rained since spring, and by September the heat had burned cattle trails and dried creek beds. Underfoot the crust of the earth was cracking. A hot wind tumbled past skeletons of abandoned houses, their hulks framed by fences about to keel over. Off to the north, amid the tallgrass of Kansas, nature was syrup sweet and the voice of the turtledove swirled throughout the land, but in the north-central Oklahoma Territory there was no sign of people, not even tombstones.

The Cherokee Strip was a slice of land sixty miles wide and two hundred miles long just south of the Kansas border and west of the Arkansas River. In earlier years the country had been considered a wilderness fit only for prairie dogs and Cherokees, who along with the Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles inhabited the region until they were shoved westward by the government to make room for homesteaders. Sections of the Oklahoma Territory, not a state for another fifteen years, had first been opened in 1889 under the Homestead Act. Four years later the Indians were paid to vacate, and their six and a half million acres was declared open for white settlement. Anyone hardy enough to stake a claim, pay the modest administration fees, and farm for five years would own a 160-acre tract.

All six and a half million acres were claimed on the day of the last great land run, Saturday, September 16, 1893. A hundred thousand pioneers enticed by the promise of a free farm or a lot in one of the four already platted town sites had been crowded into makeshift camps that week, suffering in the 100-degree heat as they prepared to race into the territory on covered wagons, buggies, buckboards, carts, and surreys, or on the backs of horses, ponies, and mules, even on bicycles or on foot. Masses of United States cavalry straddled the border at regular intervals, as if they feared a monstrous traffic jam.