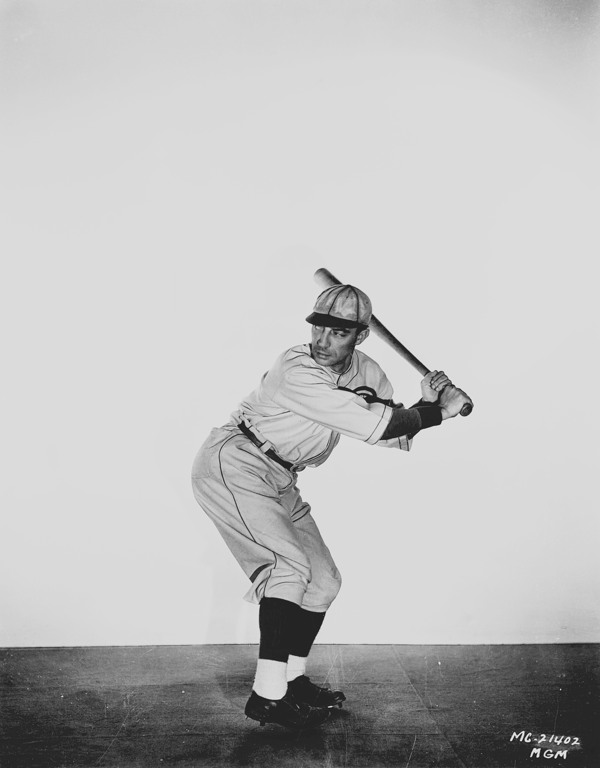

Film and baseball were Buster Keatons two great loves. The game is often referenced in his movies such as fleeting self-defense batting away of objects, pretending to play poorly in Colleges (1927) baseball sequence, and The Cameramans (1928) tour de force solo performance at Yankee Stadium. Plus, crews had to be proficient in either film or baseball, since periodic games helped Buster brainstorm.

Copyright 2018. McFarland. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/14/2022 4:32 PM via

AN: 1736881 ; Wes D. Gehring.; Buster Keaton in His Own Time : What the Responses of 1920s Critics Reveal

Account: victoria

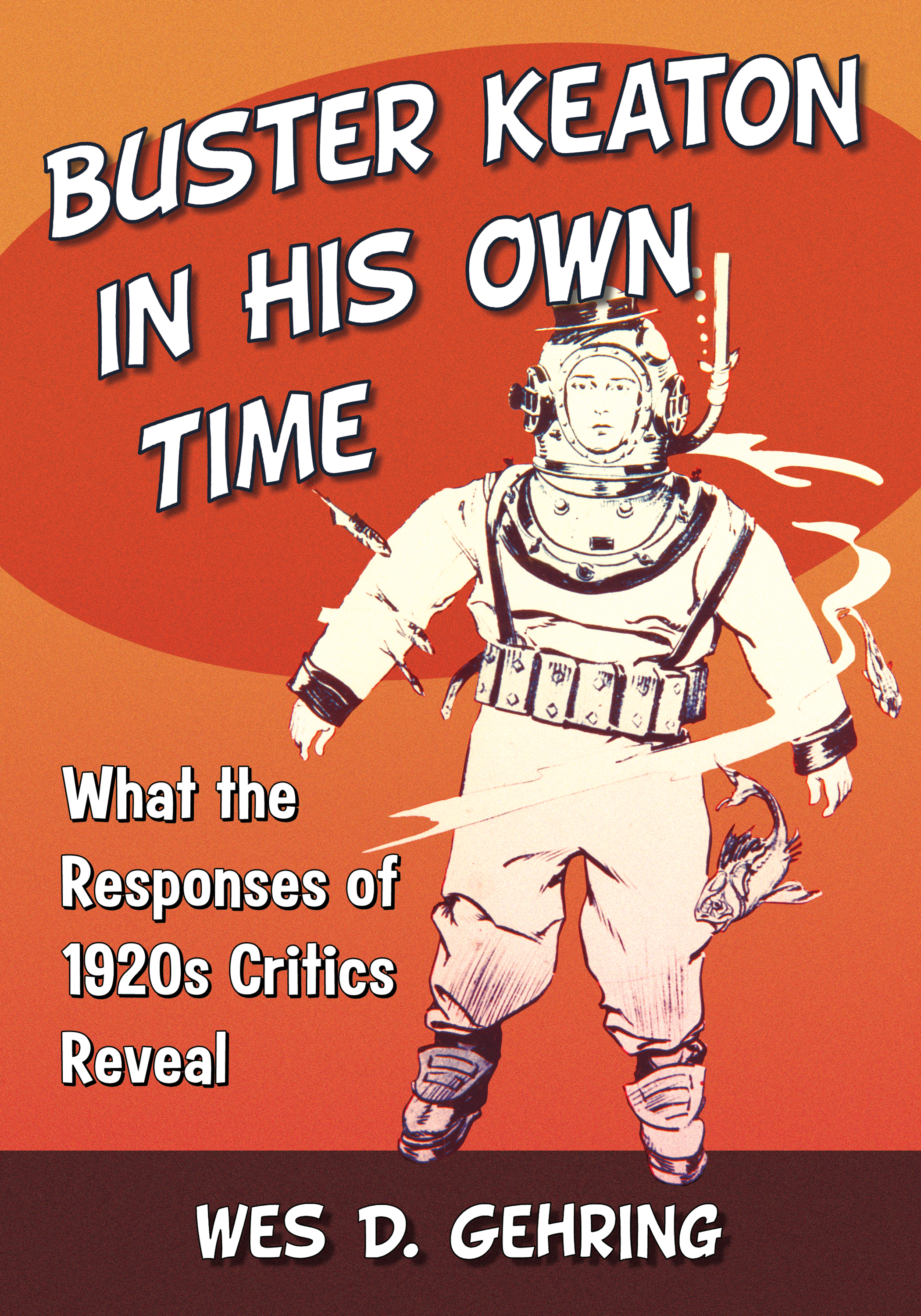

Buster Keaton in His Own Time

What the Responses of 1920s Critics Reveal

WES D. GEHRING

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

EBSCOhost - printed on 2/14/2022 4:32 PM via . All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Also by WES D. GEHRING AND FROM MCFARLAND

Movie Comedians of the 1950s: Defining a New Era of Big Screen Comedy (2016); Genre-Busting Dark Comedies of the 1970s: Twelve American Films (2016); Chaplins War Trilogy: An Evolving Lens in Three Dark Comedies, 19181947 (2014); Will Cuppy, American Satirist: A Biography (2013); Forties Film Funnymen: The Decades Great Comedians at Work in the Shadow of War (2010); Film Clowns of the Depression: Twelve Defining Comic Performances (2007); Joe E. Brown: Film Comedian and Baseball Buffoon (2006); Mr. Deeds Goes to Yankee Stadium: Baseball Films in the Capra Tradition (2004)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3326-8

2018 Wes D. Gehring. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

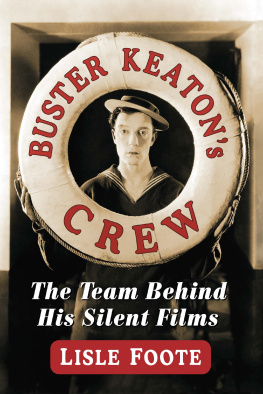

Front cover: Buster Keaton as Rollo Treadway in The Navigator, 1924 (Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

EBSCOhost - printed on 2/14/2022 4:32 PM via . All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

In memory of my mother

Marilyn McIntyre Gehring

EBSCOhost - printed on 2/14/2022 4:32 PM via . All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

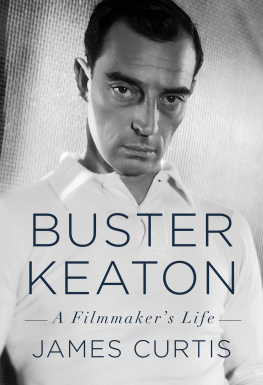

Preface and Acknowledgments

Nowhere to Run (1965)Martha and the Vandellas

By time-tripping back to 1920s Buster Keaton material, many forgotten but fascinating and often provocative items have been discovered about this pioneering existentialist. Not surprisingly, given his trailblazing Theatre of the Absurd world, his screen persona was frequently driven to run from something, be it the police (Cops, 1922), or wannabe brides (Seven Chances, 1925). Yet, with his cultish anticipation of todays dark comedy mindset, most succinctly showcased by his tombstone endings, the message was clearthere was Nowhere to Run. Thus, if Buster were to be given a belated theme song, la Charlie Chaplins composition Smile, or Groucho Marxs Hurray for Captain Spalding, nothing could be more quintessential Keaton than Nowhere to Run. Indeed, even in one of his last movies, 1965s Filmfittingly a silent short subject by Waiting for Godot playwright Samuel BeckettKeatons character is pushed to run.

With Film, first screened mere months before his death, and the release of Nowhere to Run, the world had finally caught up with his once other worldly prophetic figurefrom a nightmare to the norm. Pertinently, for a comedian who had more faith in mechanical consistency than mankind, the songs video even had the Vandellas singing in an automobile factory amidst the construction of a single car. Keaton might have masterminded the short subject from what he called his postcard-sized scripts.

Regardless, by the 1960s Keaton seemed more contemporary than Chaplin. And in the 1980s no less a figure than the BBCs most important broadcasting gift to America, Alistair Cooke, reported that British critics were calling Keaton a resurrected god. Be that as it may, the following pages examine this resurrected god in his own time when he was nickname Zero.

Nevertheless, the real task at hand here is to thank the many people who helped make this book possible. At this point, no matter how the text fairs with readers, most conscious authors feel like the director Franois Truffaut played in his film within a film from 1973s Day for Night: Shooting a movie is like a stagecoach trip. At first you hope for a nice ride. Then you just hope to reach your destination. This exhaustion can sometimes even make a writer feel like one of Star Wars (1977) bar scene characters. (Note there is no text photo of the author.) Anyway, as the acknowledgments begin, there is always the fear that someone has been missed. So if anyone is overlooked, my profound apologies. Let me start with a heartfelt thank you for my department chair, Tim Pollard. He has once again been ever so generous in every way to make this book happen. And as with all my writing, Janet Warrner supplied valuable editorial help, while Kris Scott was responsible for the computer preparation of the manuscript. Chris Flook once again was especially helpful with all technology questions and needs. Ball State emeritus professors David L. Smith and Conrad Lane provided valuable discussions about the project, and often obscure Keaton-related articles. Former BSU endowed chair (and award-winning filmmaker) Robert Mugge was also an excellent and patient sounding board. And given the texts focus on 1920s film criticism, BSUs interlibrary loan staff was especially helpful: Kerri K. McClellan, Elaine S. Nelson, Jodi L. Sanders, Lisa R. Johnson, and Karin Kwiatkowski. Plus, BSUs James Shimkus, from Information Services, always went beyond the extra mile on the odd questions.

Away from home, the New York Public Librarys main branch at Fifth Avenue and Forty-Second Street is always an invaluable source, with its two marble lions, Patience and Fortitude, standing guard at the entrance. At this location, my focus is on the tombs sectionlooking at New Yorks many seminal dead newspapers on microfilm. (Of special importance here was Diane Serrano.) The citys Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center is also a necessary stop, with its period clipping files of film artists and individual pictures.

Bowling Green Universitys (Ohio) Jerome Library, a popular culture mecca, was an invaluable source of period movie magazines. I was especially indebted to the ongoing assistance of special collection librarian Mary Zuzik. Even after two research trips, she would contact me with updates on lingering questions.

I cannot thank enough New Yorks Liz Kurtulik, from Art Resources Permissions Department, for her invaluable help in tracking down and helping to arrange permission for the reproductions of Edward Hoppers

Next page