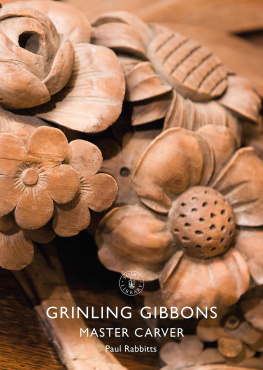

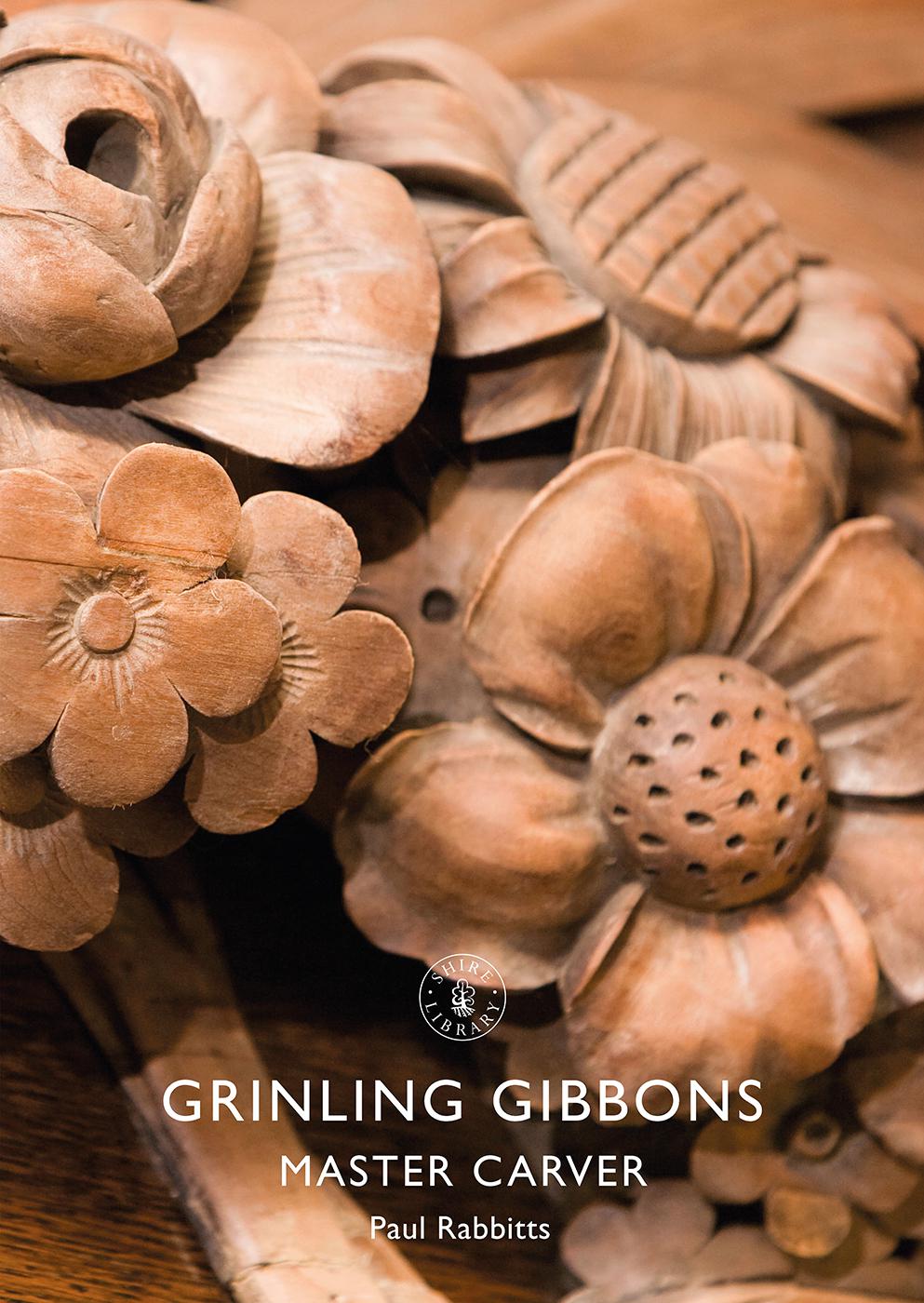

Paul Rabbitts - Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver

Here you can read online Paul Rabbitts - Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

W RITING IN ONE of the earliest biographies of Grinling Gibbons in 1914, Grinling Gibbons and the Woodwork of his Age , Henry Avray Tipping states that Gibbons requires no introduction and is already a household name, being known in the sphere of the Decorative Arts in England. Tipping also refers to him as a designer and sculptor. Yet there has been considerable debate throughout our finest periods of architecture on the role of these craftsmen, whether they were joiners, carpenters, stonemasons or other similarly s killed workmen.

In Saxon times, the carpenter was the principal lead in all matters related to building and furnishing. This continued through the Middle Ages where the carpenter maintained a dominant position, until the beginning of the fifteenth century when joiners and carvers began to be mentioned, and a broad distinction arose between those who used wood simply and constructively and those who used it for more elaborate details. The London carpenters led the way, establishing themselves as a guild with a coat of arms in 1466 and eventually receiving a Royal Charter of Incorporation in 1477. However, a hundred years later, Queen Elizabeth I gave the same privileges to joiners and ceilers. Their charter called them the mystery of Junctorum et Celutorum and the junctor elaborately joined pieces of wood with glue or nails and by means of grooves, dovetails and framing. He became the maker of a vast array of furniture including the dresser, the court cupboard, the light chair and the joined table, all of which proliferated under Elizabeth I. A fashion also emerged for the replacement of plain boarded walls with framed wainscoting, which was beginning to be introduced in many of the smaller manor houses and included mantelpieces and door frames and cases. However, if further ornamentation was required, the joiner would call in the other branch of his craft the ceiler who was also a woodworker. Tipping explains that to ceil was to cover bare walls and ceiling rafters with ornamental woodwork, and must be derived from the Latin verb, celare , to hide or cover up. However, the charter of incorporation from the Elizabethan era also described him as a caelator , or carver in bas-relief, of classical Rome. The work of the time was often described by many as clumsy and not especially refined and, in most cases, the same person was both the joi ner and ceiler.

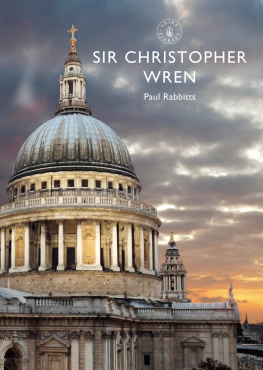

The work of Inigo Jones had an immense influence on seventeenth-century architecture and he laid the foundations for the glorious joinery that distinguished the Stuart period. This became the age of the joiner rather than the carpenter. Friction remained between the two crafts of joinery and carpentry, and their respective livery companies were frequently at loggerheads in the early part of the seventeenth century. In 1632, a committee of aldermen attempted to define the sphere of each craft but failed to satisfy the carpenters, and the rivalry continued well into the seventeenth century. This came to a head in 1672 when the Company of Joiners and Ceilers petitioned the Lord Mayor and aldermen to attempt to enforce the rules laid down in 1632, which were daily broken by the carpenters. Over time, and especially during the period of the rebuilding of St Pauls Cathedral, the carpenters were limited to plain constructional work. The abundance and excellence of joiners work increased considerably over the time with the joiners craft assuming larger and more sumptuous proportions while the forms of furniture multiplied and became more elaborate, and the output of work inc reased rapidly.

Portrait of Grinling Gibbons by John Smith, (1690).

During the early seventeenth century, the use of wainscoting continued as a general system of wall lining and was fashionable in halls and churches as well as more ordinary rooms. But wainscot design and its wider treatment was to be revolutionised in the second half of the seventeenth century. Wainscoting at the beginning of the century followed natural rules and was dictated by the material used. Oak boards of a width that could be easily obtained from an ordinary-sized oak tree were set into grooved stiles and were of sufficient thickness to give some solidity without warping. However, decoration was very simple. This was to change as, towards the end of the seventeenth century, we see enormous panels of wood. Wood was easily obtainable as a wall lining in England and it lent itself to new fashions so the joiners of the time had to adapt accordingly. By the time Grinling Gibbons was working, great panels were available, feet wide and feet high. It was of course impossible to procure boards of this size, therefore two or more boards had to be carefully glued together and the most skilful of joiners would select boards of a similar grain so the join could not be seen. These panels with their mouldings had to be cleverly built up of many sections, pieced and glued and ultimately reinforced, giving the ultimate appearance of a solid wall. The joiners of this period proved equal to the task and used the best wood available to them and, in most cases, the use of oak prevailed in churches, palaces and public buildings as well as private houses. After the joiner had prepared and partly set up his wainscoting and other woodwork, the carver would be called in, and the finish that was now demanded eventually separated the two branches of this craft. A number of these carvers of the late Renaissance period were members of the Joiners Company, but became distinguished by their specialised name that of carvers. As Tipping summarises, if ornament was now placed with more learnedness and reserve than of yore it was not used any the less. In all important designs of the period the eye rests with pleasure on large, plain surfaces, but it rests there only after having feasted on the exceeding richness of the rightly ordered and balanced decor ated portions.

Of all the wood carvers of this period, one name is synonymous with carving and was to become the master carver himself Grinling Gibbons. Gibbons has often been called the British Bernini and shared with the great Italian an ability to breathe life into still material. Carefully carved cascades of fruit and flowers, faces of cherubs with puffed out cheeks, crowds of figures and flourishes of architecture a tumultuous world of pure energy and animation were to tumble from the hands of Gibbons to grace stately homes and royal palaces across the country. Where Bernini worked with marble, however, Gibbons was a woodcarver; he was neither a joiner nor a carpenter. A more apt description would be that of art writer, William Aglionby ( 16411705 ), who called him the Michelangelo of Wood. Gibbons work was ultimately to include lucrative and prestigious commissions in St Pauls Cathedral, Hampton Court Palace and Petworth House, to name just a few. From a journeyman born in Rotterdam to the kings carver, this book celebrates Grinling Gibbons unequalled talent, his visionary genius, and his ability to transform the medium of wood into som ething magical.

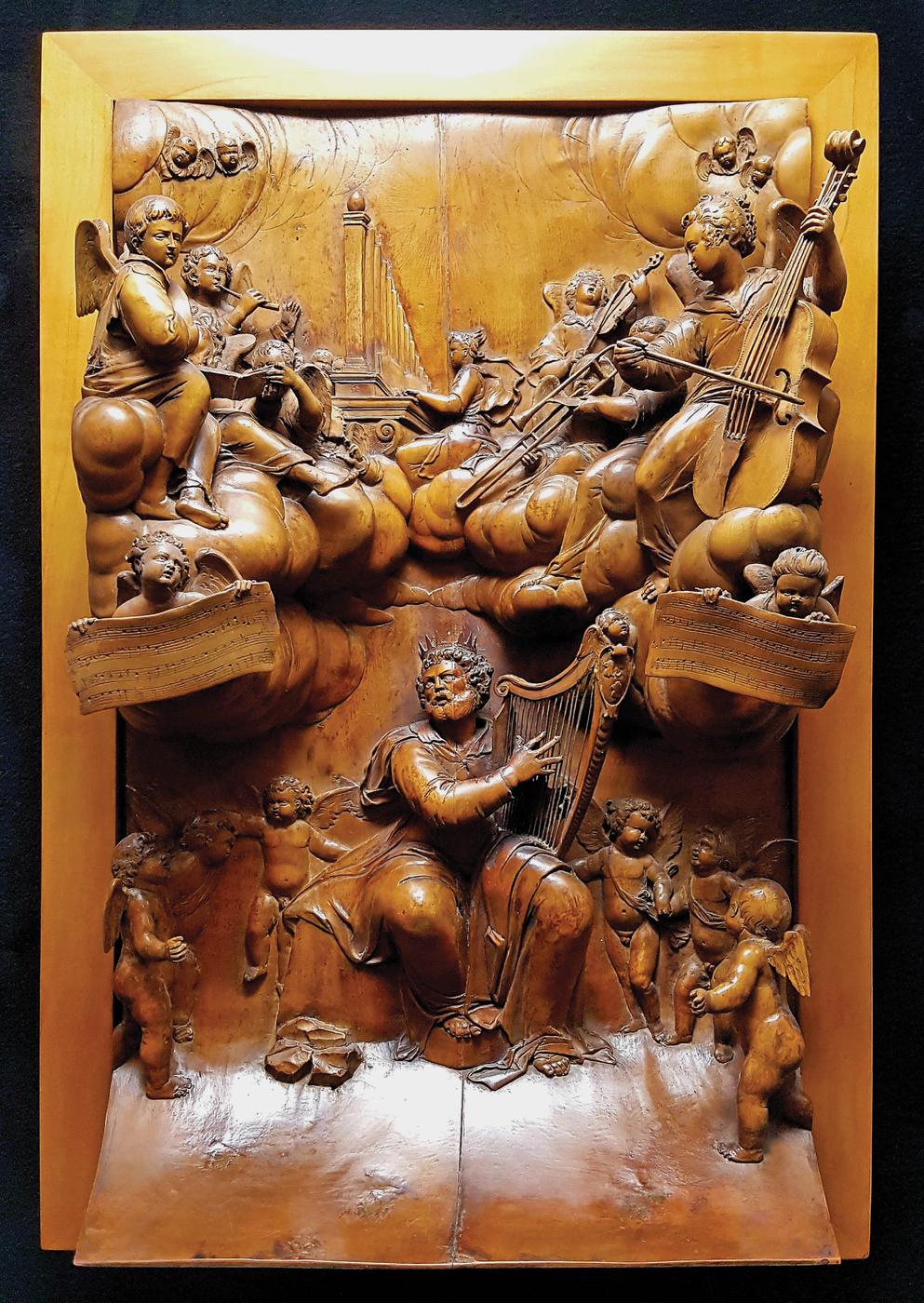

The King David relief at Fairfax House.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver»

Look at similar books to Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Grinling Gibbons: Master Carver and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.