William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright Gordon Corera 2018

Gordon Corera asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover images: Map INTERFOTO/Sammlung Rauch/Mary Evans

Other images Shutterstock; Design: Ben Gardiner

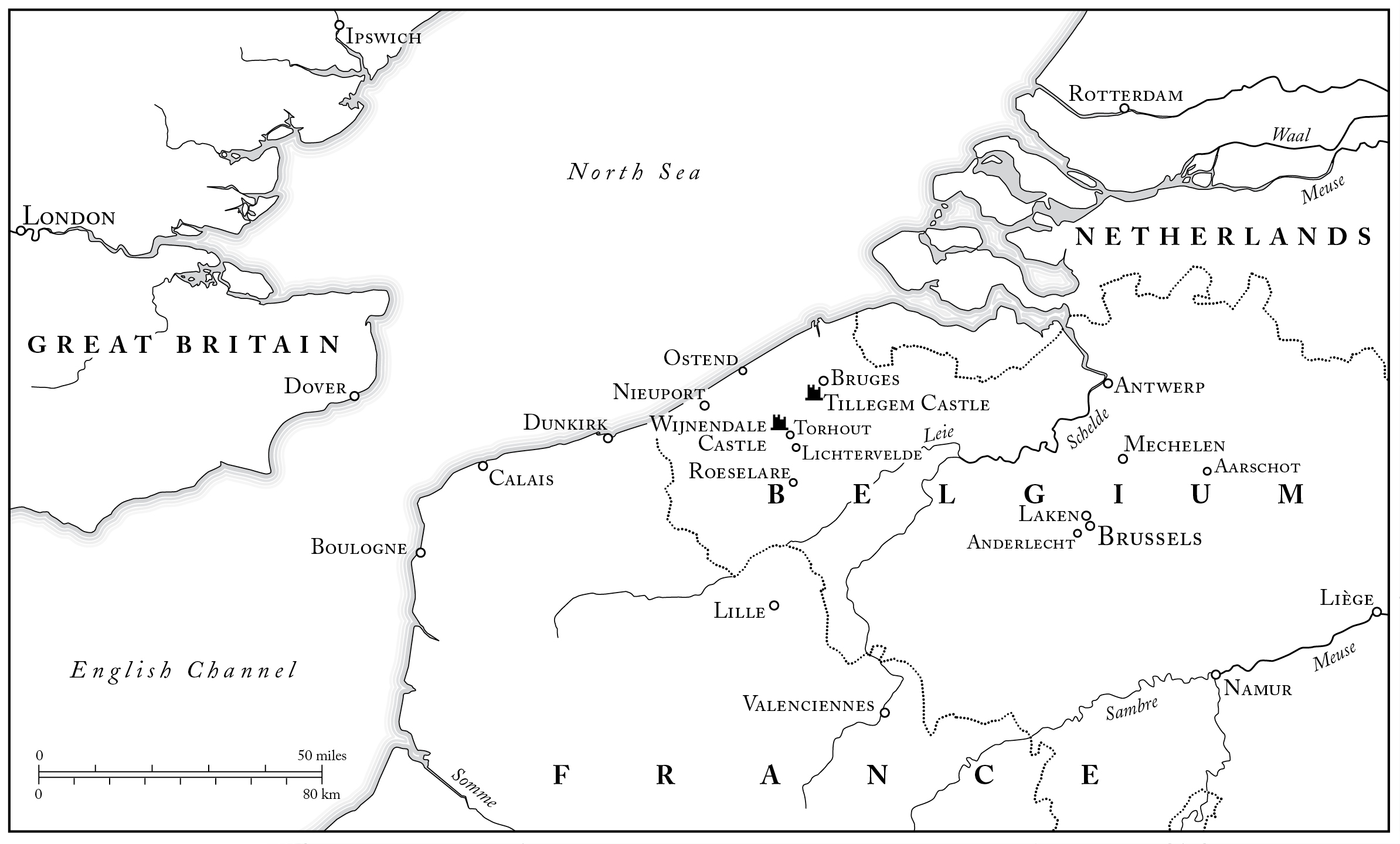

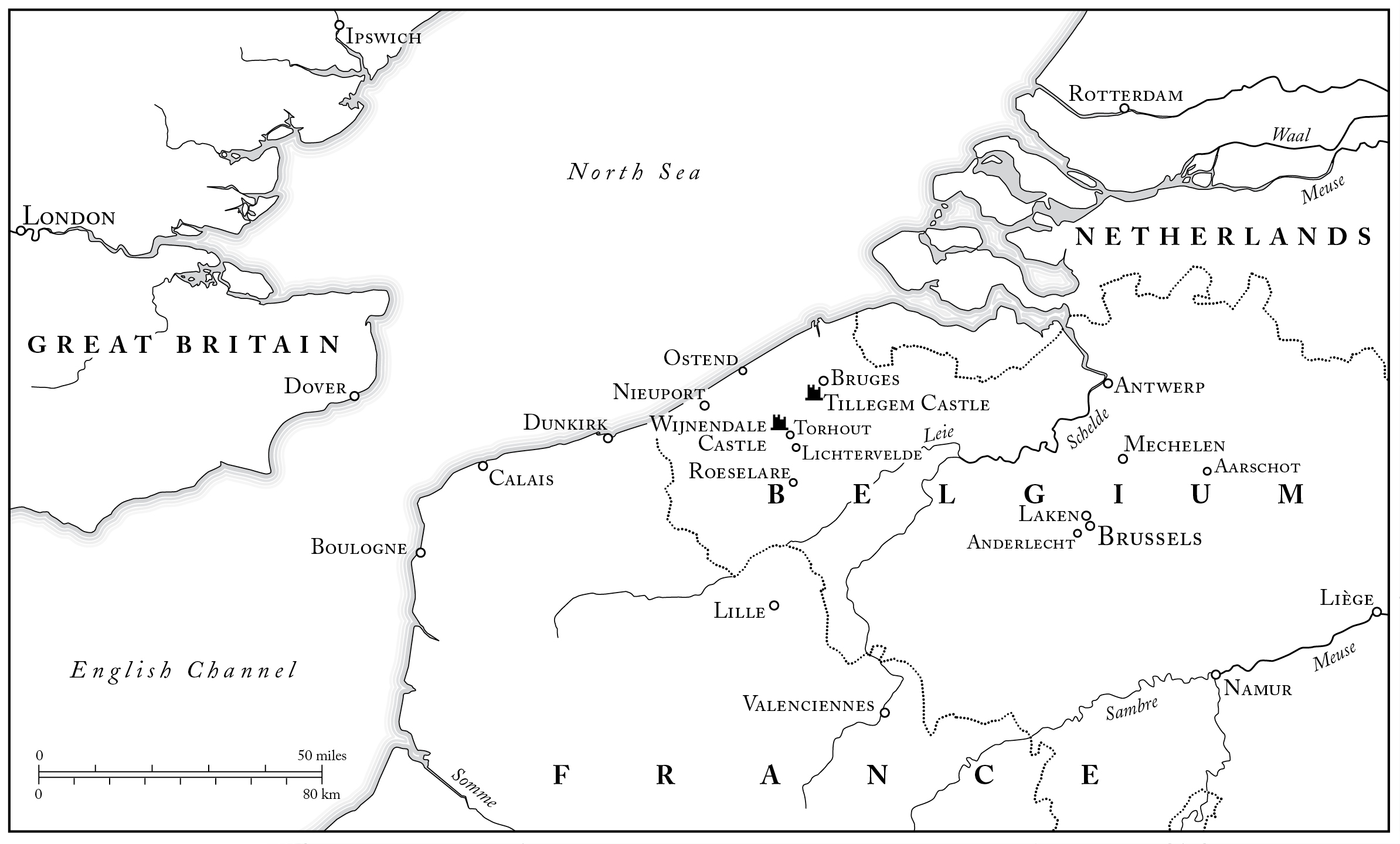

Map Martin Brown

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers will be glad to rectify any omissions in future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008220303

Ebook Edition February 2018 ISBN: 9780008220327

Version: 2018-01-16

In memory of Leopold Vindictive

and others who made their choice.

Contents

The Belgian farmer could see there was something odd in his field, something that did not belong there. It was early on a July morning in 1941, just over a year after Nazi tanks had swept through the country. As he stepped closer the farmer could make out that the unfamiliar object was a small container with a length of white material attached. Picking it up, he realized the material was a parachute but one too small for a man. Inside the box he could see something moving and a pair of eyes that peeped out at him through a small opening. Next came the unmistakable sound of a pigeon cooing. Attached to the side of the container was a message a request for help. The farmer decided this was something that he needed to consult his wife about.

It was a moment of peril one that many a British pigeon did not survive. The message made clear that this was no innocent pigeon but a very dangerous bird. It was a spy pigeon that could get the farmer and his wife killed. At this crossroads in the war, many faced with the same discovery across north-western Europe would decide it was better that the pigeon died than they did. Often villagers would make the choice more palatable by roasting and eating the bird. Others went straight to the local police station or to their Nazi occupiers and took the reward on offer for surrendering one of these pigeons. That July morning, half a dozen other birds dropped in nearby Belgian fields would be handed over to the authorities out of fear or greed.

But this farmer and his wife were not like the others. And so the first in a series of small choices was made. The wife set off by bicycle, hiding the container in a sack of potatoes. She had an idea where to go. The small local town of Lichtervelde was, like Belgium as a whole, divided by Nazi occupation. The split was delineated by alcohol. Those who frequented a local pub called De Keizer were known as whites they thought of themselves as patriots meaning they were against the occupation. Meanwhile those who frequented De Zwaan were blacks nationalists who often wore black shirts and sympathized with the Nazis. Everyone knew who was who and what side they were on.

The farmers wife parked her cycle by a grocery shop on a corner a few streets from the centre of town. She carried in the sack of potatoes nothing suspicious, since it was part of the regular drop-off of supplies for the shops owners. But she also handed over the spy pigeon to the family who ran the store. Why them? For two reasons. Everyone knew the Debaillie family were patriots three brothers and two sisters, plus assorted relatives sent to them for safety during the war. But there was another reason. One of the brothers, Michel, was a pigeon fancier.

The brothers and sisters gathered round as Michel gangly, with a mop of unruly curly hair carefully took the bird out. Like any pigeon fancier, he knew how to hold it tenderly but firmly. With the bird were a small sack of feed, two sheets of fine rice paper, a pencil, a resistance newspaper and a questionnaire. The questionnaire, like the pigeon, was from England. It asked for help: specific and dangerous help.

It was time for another decision, one that would shape the course of the lives of this family and others. To help or not to help? To spy or not to spy? To resist or not to resist? Not all were sure. Michels younger brother wanted to act. The elder thought it was dangerous. But collectively, they made their choice. If they were patriots, they were patriots.

What did they know about spying? Nothing, really. But they had some friends who might be able to help. One was a former soldier from the First World War who had a fascination with military maps. The other, more surprisingly, was a priest. By the next day, these two had arrived in the corner shop and were inducted into the secret of the pigeon. An amateur spy network, consisting of a band of friends, had been born, driven by a desire to do something about the Nazi occupation that blighted their homeland. For the first friend, the former soldier, the bird was a thing of beauty that he marvelled at, reminding him of the pheasants he kept at home. For the priest, the rice paper was what lured him in. It was like the type of paper on which he had learnt to write characters in China a decade and a half earlier. Like the paper he had used to draw maps of German positions in the last war. And so, he knew, the paper and the pigeon were drawing him into the world of espionage to make him once again priest, patriot and spy.

Like the farmer in the field, I stumbled across the oddities of Operation Columba by chance one morning. I was covering a quirky news story about a dead pigeons leg found in a chimney in Surrey. Attached to the bony leg was a message which had stumped GCHQs top code-breakers. They had been unable to decipher what the seemingly random series of letters meant. No one was even sure who the pigeon had been sent by, and everyone seemed quite surprised to find that pigeons had been used in the Second World War.

Perhaps there was some clue in the National Archives in Kew which could unlock this pigeons secrets? I spent a morning pulling up any and every file that looked as if it might relate to pigeon messages in the Second World War. There were more than I thought, and it was a bewildering induction into a world I had never even known existed. But amidst the interminable accounts of which department should pay for pigeon feed, or what rank of personnel were required for a particular RAF loft, one file that landed on my desk immediately stood out.

Apart from the dates, the front cover bore only two words. One was Secret; the other, in elegant handwriting, was Columba. At the top was a photo of a pigeon someone had cut out. Just below the pigeon was a cartoon also cut out, this time from a newspaper of Hitler lying prostrate on the floor. This gave the impression that the pigeon had done on the Fhrer what pigeons do, leading him to fall over. At the bottom of the cover was another cartoon, this one of an RAF plane flown by Winston Churchill with a familiar cigar in his mouth and his fingers held up in his V for Victory sign. The file clearly contained details of a secret operation. But it looked utterly unlike any I had seen before. What kind of people would, in the midst of war, encase the contents of their clandestine work in such colourful even playful packaging?