Following the career of Ronald Seth has led me down a number of interesting byways, and I wish to express my gratitude for their assistance to the following people:

Pekka Erelt, Meelis Maripuu, Malle Kivivli, Helga Riibe and Andres Kasekamp for their advice and expert knowledge on matters Estonian; Axel Wittenberg for delving into the Militr-archiv in Freiburg; Philip Pattenden, whose information on Seths undergraduate days was invaluable; Blair Warden and the Literary Estate of Lord Dacre of Glanton for allowing me access to the correspondence between Seth and Hugh Trevor-Roper; Patrick Salmon and Tom Munch-Petersen for long years of friendship and shared expertise on northern Europe; and a special thanks to Laurie Keller, whose genealogical expertise and constant support has both assisted and inspired me.

Contents

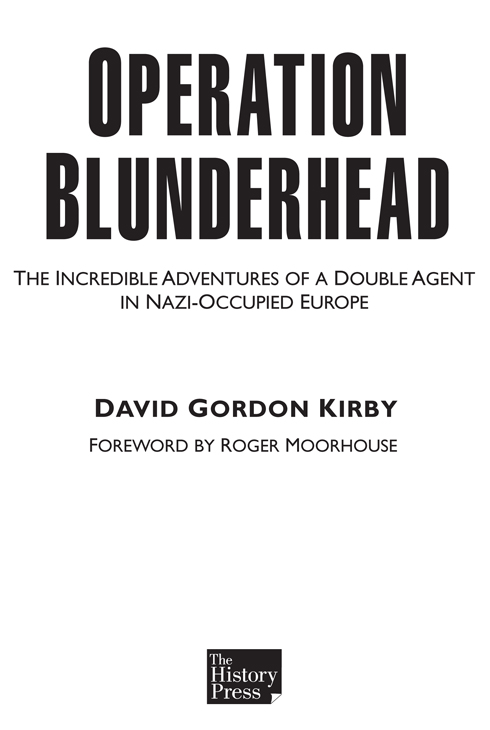

by Roger Moorhouse

For a long time, when we thought of Britains wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE), the image that most probably sprang to mind was something akin to James Bond: the cold-eyed, ruthless assassin or saboteur, stalking occupied Europe and striking fear into Nazi hearts. There was something in this, of course. SOE instructed by Winston Churchill to set Europe ablaze in 1940 scored some notable successes, most famously assassinating Himmlers deputy Reinhard Heydrich in 1942 and sabotaging German efforts to make heavy water at Vemork in Norway the following year. It even made plans to assassinate Hitler himself.

But, for all their dashing and their derring-do, SOE agents were not all James Bond clones. They were, instead, an eclectic bunch: men and women, drawn from many nationalities and all walks of life, encompassing everyone from safecrackers to bankers, secretaries to princesses. Clearly, the stereotype of the chisel-jawed action hero is one which requires substantial revision.

Yet, even bearing all of that in mind, the story of Ronald Seth is still a remarkable one. Seth, a 31-year-old former schoolteacher, was parachuted into German-occupied Estonia in the autumn of 1942 ostensibly to carry out acts of sabotage in a plan code-named Operation Blunderhead. It was a very rare example of a privateer-SOE mission, as the idea had come from Seth himself then a humble RAF officer rather than being dreamt up from within SOE. Moreover, unlike the vast majority of SOE missions, Seth had no support network on the ground at his destination; though he knew the country well, he was essentially going in blind. This combination of factors might well account for the peculiar choice of name given to the operation: perhaps someone within SOE was thereby expressing their concern about the missions feasibility.

In the event, such concerns would be amply borne out. Swiftly captured by local Estonian militiamen and handed over to the Germans, Seth was initially scheduled for execution before persuading his captors that he might be of some use to them. He then embarked on a remarkable odyssey across Europe, surviving on his wits, by turns seducing and frustrating his German captors. Finally, he was sent over the Swiss border, in the dying days of the war, apparently on a mission from Himmler to secure a separate peace with the Western Allies.

Seths story full of pseudonyms, mistresses, aristocrats and double dealing is one that almost seems to have sprung from the fraught imagination of a penny novelist. Yet it is true. Nonetheless, Seth was clearly not above embellishing it, both at the time and in his later memoir. His penchant for spinning a yarn, it seems, was irresistible. He told his German captors, for instance, that he knew Churchill personally, and that he was involved in a movement to restore Edward VIII to the throne.

To some degree, of course, such invention was an essential part of the game of survival that Seth was playing with the Germans. Many prisoners before him had made out that they were well connected so as to save their lives or even just secure better treatment; among them commando Michael Alexander, who claimed upon capture to be related to Field Marshal Harold Alexander, and Red Army soldier Vassili Korkorin, who passed himself off as Molotovs nephew. At first glance, then, it might seem that Seth was merely following in that necessarily mendacious tradition, saving his own neck by making himself appear to be someone who might be of value to Berlin.

Yet, there is more to Seths story than meets the eye. For one thing, beyond the requirements of self-preservation, he seems to have embellished his own account of his exploits at almost every turn, adding details, vignettes and narratives that he borrowed from others, or else dreamt up for himself. Little wonder, perhaps, that SOE would later consider him to be royally unreliable, and tiring of his Walter Mitty-ish excesses brand him as extremely untruthful and seek to stop the publication of his post-war memoir.

More importantly, perhaps, away from the hyperbole of his later memoir account, it seems that Seth may have played his wartime role of the person of interest rather too well, straying over the line that divides self-preservation from active collaboration. Certainly there were more egregious examples than his own, and there was never sufficient evidence for any legal case against him to be mounted, but nonetheless Seth sailed rather close to the wind. Immediately after his capture, for example, he was already stressing his anti-Soviet credentials and offering to work for the Germans against Moscow. In time, he would inhabit a dubious Gestapo safe house in Paris and act as a stool pigeon in a British POW camp, informing on his fellow prisoners to the German authorities. Finally, he would graduate to the most exalted role of all: that of Himmlers supposed emissary to London.

David Kirbys book is a fascinating examination of this complex, sometimes bewildering story. It is certainly a most impressive tale. Ill-starred as his mission was, it was no mean feat for Seth to have survived his capture in German-occupied Estonia in 1942. The murderous fate that other captured SOE agents suffered, such as Noor Inayat Khan or Violette Szab showed what treatment he might ordinarily have expected. Yet, what followed even if one strips away the mythology and half-truths was truly remarkable.

Beyond telling that fascinating story, the book has additional merits. Firstly, the author a former professor of history from London University expertly applies his critical skills, forensically dissecting the myriad layers of exaggeration, secrecy and obfuscation that have enveloped Seth and his tale almost from the beginning, sorting the plausible from the improbable. This is an important task. Historians, like seasoned investigators, always seek corroborating documentary evidence, but in Seths case it is more vital than ever.

The second merit is that, whilst rigorously applying those formidable investigative skills, Kirbys is nonetheless a sympathetic approach. He views Seth as a curiosity, someone who though he might have straddled the boundary between dissembler and fantasist is nonetheless worthy of serious study and objective assessment. Moreover, as he notes at the end of the book, Seth seems to have had a curious persuasive quality, which made one want to believe him, even if one is not always quite sure why.

There are aspects of Seths story, one fears, that can perhaps never be satisfactorily clarified, but David Kirbys skilful, sober study is a fitting epitaph to one of the most peculiar episodes of the Second World War.

Roger Moorhouse, 2015

Next page