T HE BELGIAN FARMER could see there was something odd in his field, something that did not belong there. It was early on a July morning in 1941, just over a year after Nazi tanks had swept through the country. As he stepped closer the farmer could make out that the unfamiliar object was a small container with a length of white material attached. Picking it up, he realized the material was a parachutebut one too small for a man. Inside the box he could see something moving and a pair of eyes that peeped out at him through a small opening. Next came the unmistakable sound of a pigeon cooing. Attached to the side of the container was a messagea request for help. The farmer decided this was something that he needed to consult his wife about.

It was a moment of perilone that many a British pigeon did not survive. The message made clear that this was no innocent pigeon but a very dangerous bird. It was a spy pigeon that could get the farmer and his wife killed. At this crossroads in the war, many faced with the same discovery across northwestern Europe would decide it was better that the pigeon died than they did. Often villagers would make the choice more palatable by roasting and eating the bird. Others went straight to the local police station or to their Nazi occupiers and took the reward on offer for surrendering one of these pigeons. That July morning, half a dozen other birds dropped in nearby Belgian fields would be handed over to the authorities out of fear or greed.

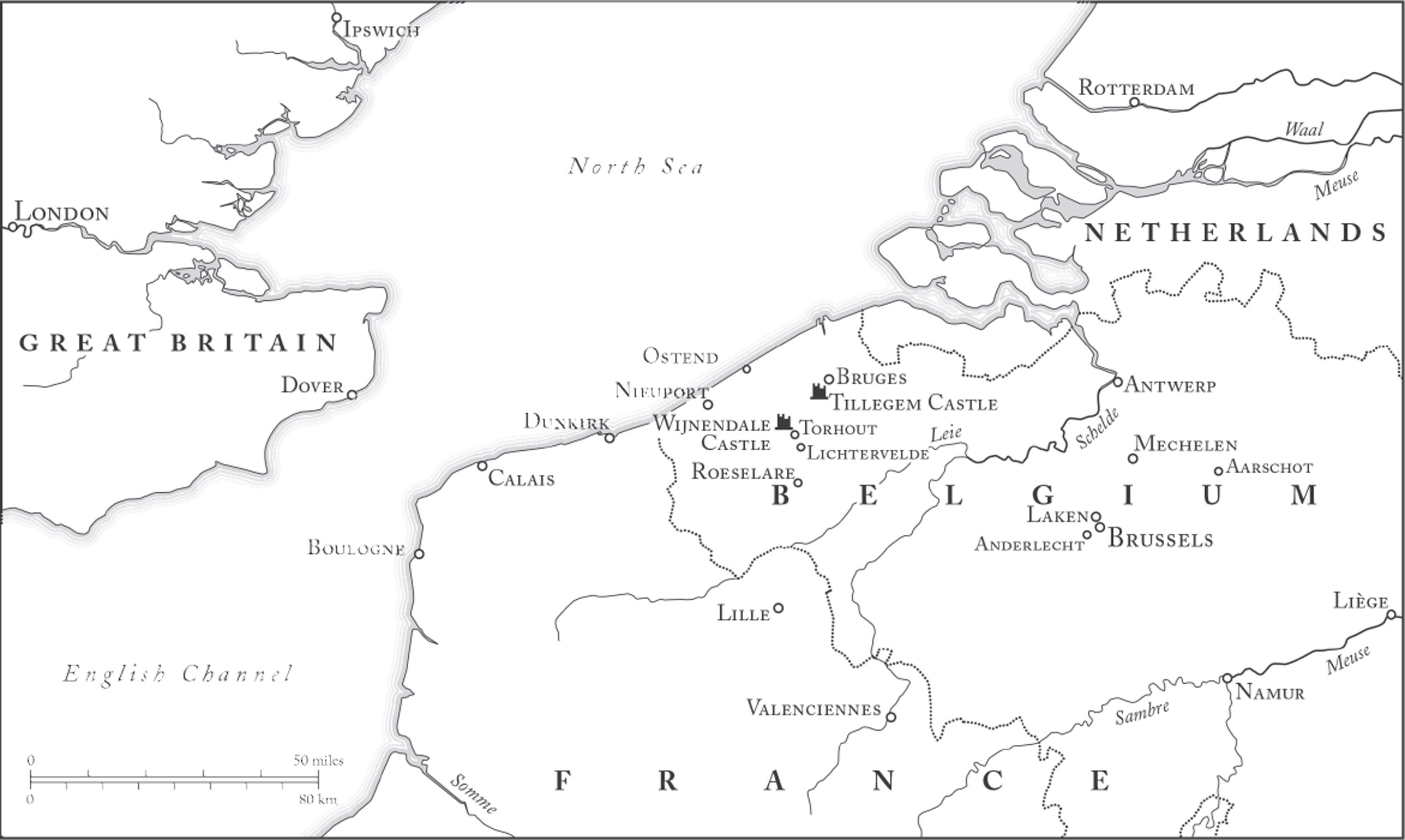

But this farmer and his wife were not like the others. And so the first in a series of small choices was made. The wife set off by bicycle, hiding the container in a sack of potatoes. She had an idea where to go. The small local town of Lichtervelde was, like Belgium as a whole, divided by Nazi occupation. The split was delineated by alcohol. Those who frequented a local pub called De Keizer were known as whitesthey thought of themselves as patriots, meaning they were against the occupation. Meanwhile, those who frequented De Zwaan were blacksnationalists who often wore black shirts and sympathized with the Nazis. Everyone knew who was who and what side they were on.

The farmers wife parked her cycle by a grocery shop on a corner a few streets from the center of town. She carried in the sack of potatoesnothing suspicious, since it was part of the regular drop-off of supplies for the shops owners. But she also handed over the spy pigeon to the family who ran the store. Why them? For two reasons. Everyone knew the Debaillie family were patriotsthree brothers and two sisters, plus assorted relatives sent to them for safety during the war. But there was another reason. One of the brothers, Michel, was a pigeon fancier.

The brothers and sisters gathered around as Michelgangly, with a mop of unruly curly haircarefully took the bird out. Like any pigeon fancier, he knew how to hold it tenderly but firmly. With the bird were a small sack of feed, two sheets of fine rice paper, a pencil, a resistance newspaper and a questionnaire. The questionnaire, like the pigeon, was from England. It asked for helpspecific and dangerous help.

It was time for another decision, one that would shape the course of lives for this family and others: To help or not to help? To spy or not to spy? To resist or not to resist? Not all were sure. Michels younger brother wanted to act. The elder thought it was dangerous. But collectively, they made their choice. If they were patriots, they were patriots.

What did they know about spying? Nothing, really. But they had some friends who might be able to help. One was a former soldier from the First World War who had a fascination with military maps. The other, more surprisingly, was a priest. By the next day, these two had arrived in the corner shop and were inducted into the secret of the pigeon. An amateur spy network, consisting of a band of friends, had been born, driven by a desire to do something about the Nazi occupation that blighted their homeland. For the first friend, the former soldier, the bird was a thing of beauty at which he marveled, reminding him of the pheasants he kept at home. For the priest, the rice paper was what lured him in. It was like the type of paper on which he had learned to write characters in China a decade and a half earlier. And it was like the paper he had used to draw maps of German positions in the last war. And so, he knew, the paper and the pigeon were drawing him into the world of espionageto make him once again priest, patriot and spy.

L IKE THE FARMER in the field, I stumbled across the oddities of Operation Columba by chance one morning. I was covering a quirky news story about the leg of a dead pigeon found in a chimney in Surrey. Attached to the bony leg was a message that had stumped top code breakers for Britains Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). They had been unable to decipher what the seemingly random series of letters meant. No one was even sure who the pigeon had been sent by, and everyone seemed quite surprised to find that pigeons had been used in the Second World War.

Perhaps there was some clue in the British National Archives in Kew that could unlock this pigeons secrets. I spent a morning pulling up any and every file that looked as if it might relate to pigeon messages in the Second World War. There were more than I thought, and it was a bewildering introduction into a world I had never even known existed. But among the interminable accounts of which department should pay for pigeon feed, or what rank of personnel was required for a particular RAF loft, one file that landed on my desk immediately stood out.

Apart from the dates, the front cover bore only two words. One was Secret; the other, in elegant handwriting, was Columba. At the top was a photo of a pigeon someone had cut out. Just below the pigeon was a cartoonalso cut out, this time from a newspaperof Hitler lying prostrate on the floor. This gave the impression that the pigeon had done on Der Fhrer what pigeons do, leading him to fall over. At the bottom of the cover was another cartoon, this one of an RAF plane flown by Winston Churchill with a familiar cigar in his mouth and his fingers held up in his V for Victory sign. The file clearly contained details of a secret operation. But it looked utterly unlike any I had seen before. What kind of people would, in the middle of a war, encase the contents of their clandestine work in such colorfuleven playfulpackaging?

Loosening the ribbon that bound the file, I uncovered riches inside. The file had nothing to do with the secret message found in the chimney. But it was far more interesting. The riches came in the form of tiny pink slips of paper. These were messages from ordinary people living under Nazi rule in occupied Europe that had been brought back by pigeon. They were filled with the day-to-day realities of wartime and offered a remarkable insight into the small frustrations and dark tragedies of life under occupation. And then I came across Message 37. It was unlike anything else. All the other messages had been written up into formal notes, but in this case a copy of the original message had been included in the archive, clearly because it was something special. It looked more like a work of art than an official document. There was tiny, beautiful inky writing, too small to read with the naked eye and densely packed into an unimaginably small space. A swirling symbol as a signature. And maps, detailed colorful maps. Most of the other messages produced intelligence reports that were half a page or perhaps a page long. Message 37rolled up tightly into the size of a postage stamp so it could fit into a cylinder attached to a pigeons legproduced an astonishing twelve pages of raw intelligence. And it had clearly had a profound impact on the team running Columba. The intelligence must have left an impression on everyone who saw itand many did, as it was passed around the highest levels of government, many referring to it in almost reverential terms.