SHOPPING FOR BOMBS

SHOPPING FOR BOMBS

Nuclear Proliferation, Global Insecurity, and the Rise and Fall of the A. Q. Khan Network

GORDON CORERA

2006

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Copyright 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Corera, Gordon.

Shopping for bombs : nuclear proliferation, global insecurity, and the rise and fall of the A. Q. Khan network / Gordon Corera.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-530495-4 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-19-530495-0 (cloth)

1. Nuclear nonproliferation.2. Security, International.3. Khan, A. Q. (Abdul Qadeer), 1936I. Title.

JZ5675.C67 2006

623.4'5119092dc22

2006012510

In memory of Bernard Corera

Contents

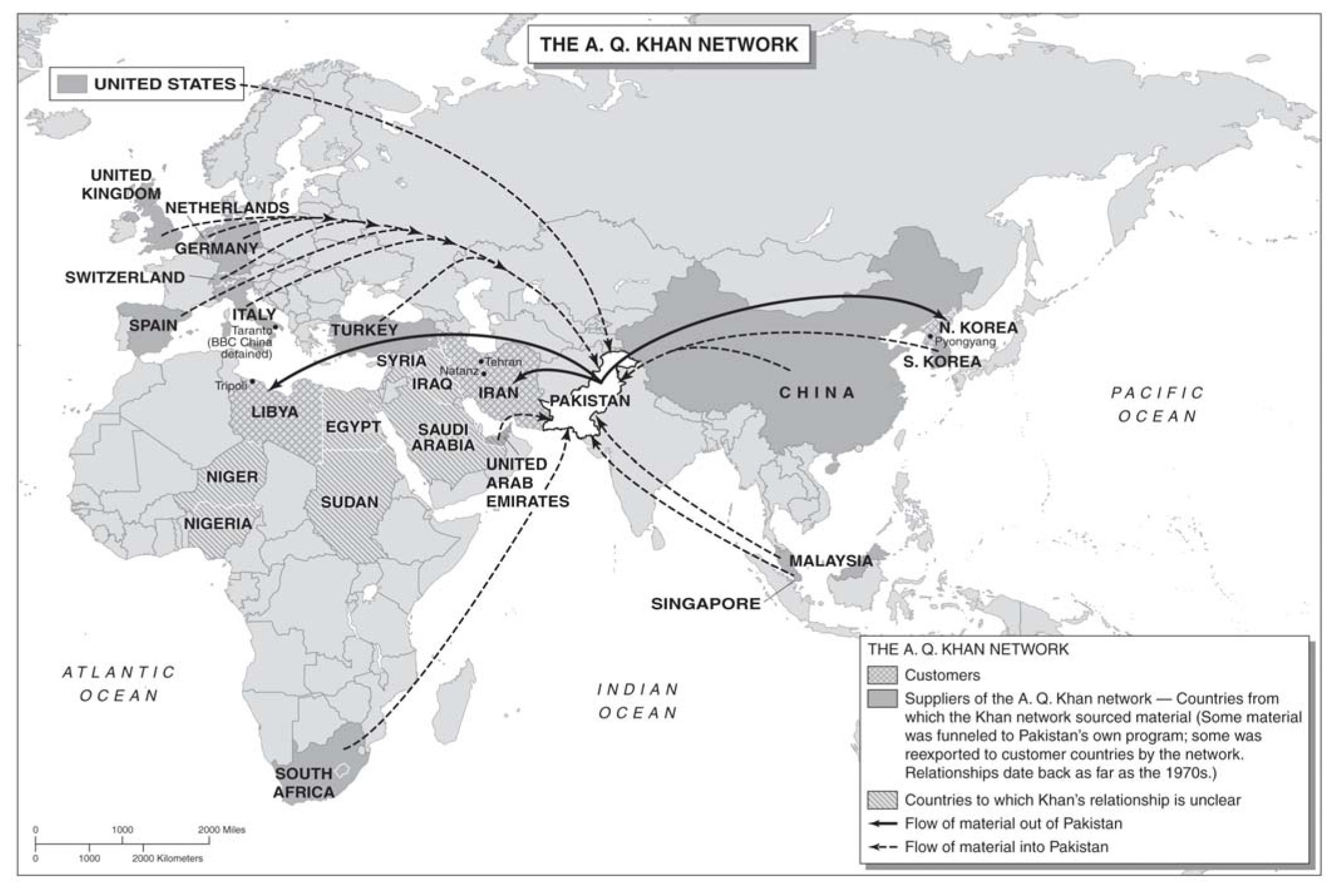

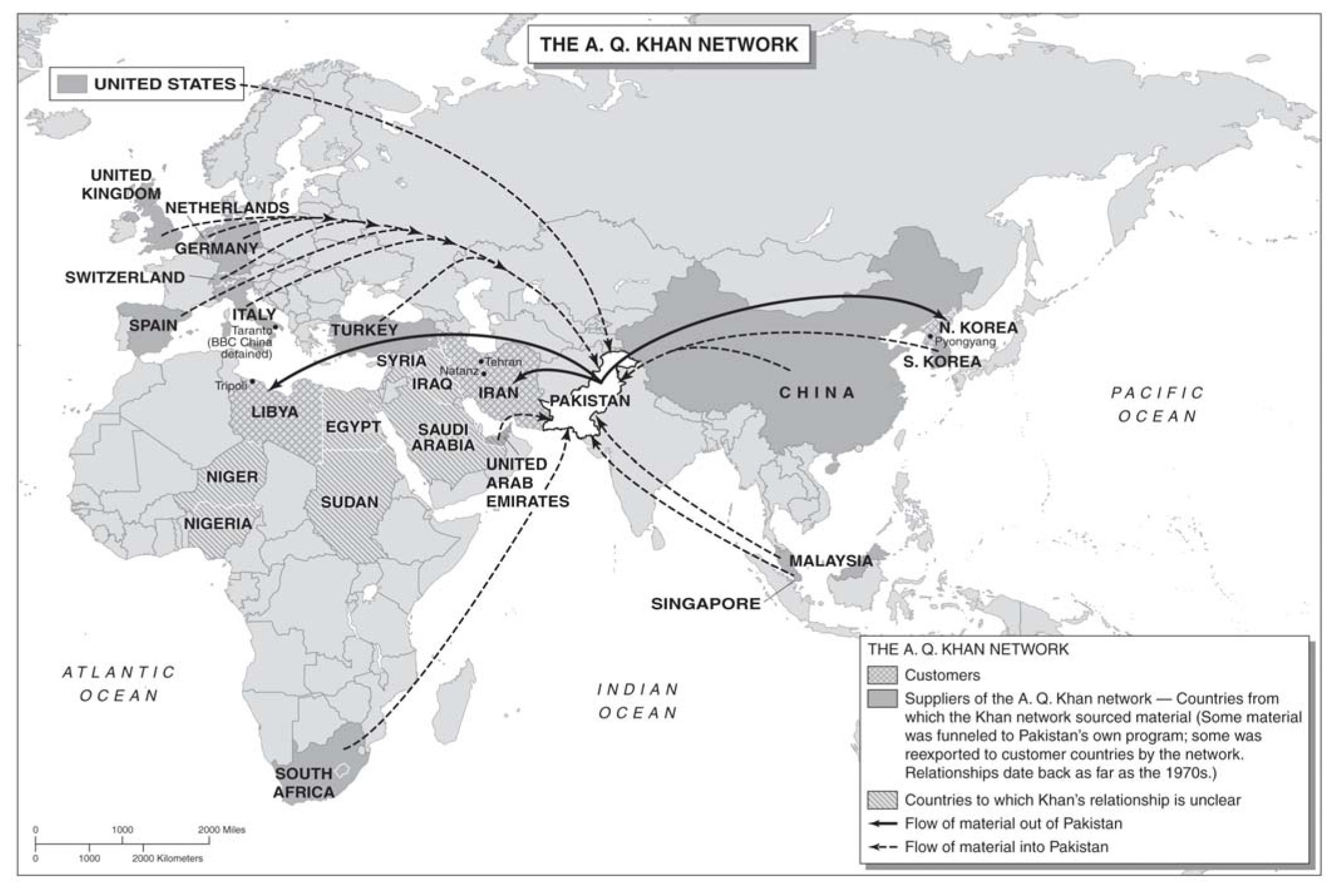

IT WAS JUST AFTER MIDNIGHT when the BBC China made its unscheduled stop. It would be gone again in two hours. The German Secret Service had contacted the ships owners in Hamburg, Germany, asking for help. The owners radioed the vessel as it passed through the Suez Canal instructing it to change course. Dont ask any questions, the captain was told. Waiting in the cold night air, the team at the dock in Taranto knew they would have to work fast to identify five forty-foot cargo containers by serial number and then remove them from amongst the more than two hundred on board. The BBC China had to resume its voyage without anyone knowing what had happened. Its ultimate destination was the Libyan capital Tripoli.

The containers journey had begun in August in a factory in Malaysia. A close-knit team working between Americas CIA and Britains Intelligence Service received a tip-off in mid-September that a consignment of important goods had arrived at the bustling hub of Dubais free-trade zone where they would be loaded onto a tramp steamer.

By the time the team had identified the boat as the BBC China, it had already left port. After a frantic search, it was found slowly snaking its way through the Suez Canal. From then on, the ship was closely watched. But until the containers were finally prised open at the port in Italy, the tension was palpable amongst those involved in the operation. What if they were filled with soft toys?

The interception of the BBC China had come after a difficult, even depressing summer for the small team working jointly between Americas Central Intelligence Agency and Britains Secret Intelligence Service (formally known as SIS although often known as MI6). Over the previous years, they had pieced together a picture of an unprecedented global black market, supplying the most deadly nuclear technology to some of the worlds most dangerous states. They had watched and waited for an opportunity to break the network but it had proved frustratingly difficult and slow. Meanwhile, the network was still churning out more sensitive material and looking for more customers. Then in the spring of 2003, a golden opportunity seemed to have arisen when MI6 was contacted by one of the networks customers who wanted to talk. But by the summer, negotiations with Libya had stalled. Thanks to the intelligence penetration of the network, the United States and UK knew that the Libyans were being far from honest about what they were up to. Was this going to be another lost opportunity? Something had to be done to force the issue.

The opening of the containers led to a wave of relief from the team. Inside were thousands of aluminium componentspositioners, casings, pumps, and flangers. There were all packed in wooden boxes bearing the logo SCOPE. No one but a trained expert would have known that these were for a centrifuge, the device that enriches uranium, the heart of a clandestine nuclear program.

The United States and UK kept the interception of the BBC China secret from the wider world for many months, but within hours they set in motion a chain of events to exploit its fleeting diversion. A senior MI6 officer would call his Libyan opposite number and demand an explanation. Within weeks, a team of CIA and MI6 officers would finally be taken into the heart of Colonel Gadaffis nuclear project. Soon after, the Libyan leader would shock the world by announcing he was giving up something that few realized he hadan active nuclear weapons program.

And for the man who had provided almost that entire capability, including the cargo of the BBC China, this was also the beginning of the end. The curtain was slowly coming down on the decades-long career of Pakistani scientist, spy, and national hero, A. Q. Khan, who had been peddling his wares as a salesman of the darkest most closely held nuclear secrets. As with the Libyans, the endgame would not be without its bumps along the road. A week before the BBC Chinas interception, the CIA director had begun the process of putting Khan out of business in a meeting with Pakistans leader in the unusual confines of a suite in a New York hotel. In a detailed briefing that stunned President Musharraf of Pakistan, George Tenet had explained just how much the U.S. government knew regarding Khans activities. And within hours of the BBC Chinas interception, a senior U.S. diplomat would arrive in Islamabad to drive home the message that the time for action had come. The end was at hand for Khan and his network. But those few individuals had already managed to do untold damage by spreading the most secret, dangerous nuclear technology across the world.

ALTHOUGH IT HAD BEEN MONTHS IN PREPARATION, President Eisenhower was still rewriting his speech on the morning of December 8, 1953. His plane circled for half an hour before landing at LaGuardia airfield in New York. From there, he traveled to the United Nations where an audience of three and a half thousand was waiting for an address that would come to define the worlds approach to nuclear technology for the coming decades.

In the few, but eventful, years since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States was already losing its monopoly on nuclear weapons. More and more states were seeking the bomb as part of the relentless quest for security, power, and prestige in the international arena. Intense scientific research, atomic espionage, and an occasional helping hand from others were in turn delivering this deadly capability to the doorsteps of more and more states. The arms race between the United States and the USSR and the spread of nuclear weapons would be the defining national security challenge of the coming years. Eisenhowers speech was designed to inaugurate a public debate on how this proliferation challenge should be met. In his diary, he wrote of his clear conviction that the world was racing toward catastrophe.

![Ausma Zehanat Khan [Ausma Zehanat Khan] - The Black Khan](/uploads/posts/book/142204/thumbs/ausma-zehanat-khan-ausma-zehanat-khan-the-black.jpg)