To Government College Lahore (Pakistan), my alma mater, whose motto Courage to Know continues to inspire me;

To Nottingham Universitys School of Law (United Kingdom), where I studied international law, and whose motto A city is built on wisdom nourished in me the unquenchable thirst for learning;

And to Tufts Universitys Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy, from where I received my doctorate, and whose motto Peace and Light engendered in me a passion to search for peace within and outside.

1

INTRODUCTION

FRAMING THE QUESTIONS

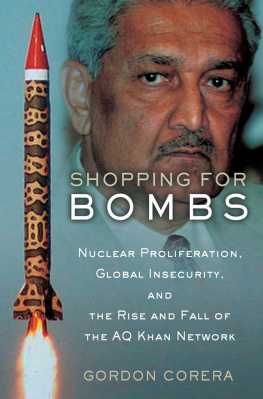

I distinctly remember an interesting conversation with Pakistani nuclear scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan (A. Q. Khan) at an event celebrating his achievements as father of the Pakistani bomb at the Marriott hotel in Islamabad in early 1994, during which he delivered a lecture on regional security challenges. Like most people in the country, I grew up venerating him as the nations saviour for his role in Pakistans nuclear programme and his contributions towards building Pakistans nuclear bomb. Meeting him face to face, I was in total awe, but his charismatic personality and warm handshake further attracted me to him. A retired senior military officer introduced me to him, and perhaps that was the best way to catch Khans attention. I was amazed by his keen interest in my educational background and career plans, and he was especially interested to know why I came to attend his event and what I had learnt from it. All of his main arguments revolved around the notion that Pakistan was now capable of dealing with the Indian threat given that Khan and his associates had made the countrys security foolproof through the nuclear option.This assertion had been drilled into the Pakistani psyche through the media and state communications throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

In 2000, however, I faced a serious dilemma when I was tasked to evaluate evidence against Khan while I was serving as deputy director of investigations at Pakistans National Accountability Bureau (NAB) in Islamabad. General Pervez Musharraf had constituted the NAB in October 1999 after he overthrew the countrys democratic order and imposed military rule.The organization initially worked under his direct supervision. I had great admiration for Khan, but what I found in the official dossiers with which I was provided created serious doubts in my mind about the transparency of the nuclear programmes financial management and the integrity of those at the helm of affairs, including Khan. General Musharraf, as chief executive of the country, had instructed the NAB to consider pursuing a corruption case against Khan. I cannot here go into details of what was documented in the files, nor I can vouch for the authenticity of the charges against him. However, what can I share is what I recommended to the chairman of the organization. I argued that even if all the allegations were true, this case was too big for the NAB to handle.The nascent organization was assigned to probe and prosecute corrupt politicians, bureaucrats, and businessmen, and starting off with countrys most popular person was not, in my view, a good idea. It could have proved to be the NABs death knell, so perhaps institutional interests also prompted me to make such an assessment. In addition, with my law education and police training, I knew full well that intelligence reports and unverified statements by colleagues do not constitute legal evidence. My recommendation not to pursue the case through the NAB was acceptedand I have no regrets about it, as it was the right thing to do under the circumstances. I would guess that senior officials also weighed in with similar concerns.What was a total surprise to me, however, was the revelation that many senior military officialsboth in the military hierarchy and within the nuclear programmewere very critical of Khan. Obviously they knew something that I had no clue about.To be fair, I must add that there were no direct nuclear proliferation charges in the said case. Interestingly, Khan was increasingly sidelined from his nuclear infrastructure management role after Musharrafs arrival in Islamabad.

The 2003 disclosures about the clandestine sale of Pakistans nuclear technology to Iran, North Korea, and Libya forced Islamabad to move against Khan. On 4 February 2004 he addressed the Pakistani nation on television, confessing: The investigation has established that many of the reported activities did occur, and that these were invariably initiated at my behest. This was a devastating blow to Pakistans image as well as its morale. For Pakistan to have successfully developed nuclear weapons was nothing short of a miracle, and the nation took immense pride in it.

Irrespective of who was the prime culprit in Pakistan, in the eyes of the West (to borrow the words of MIT scholar Jim Walsh), Pakistan is absolutely the biggest and most important illicit exporter of nuclear technology in the history of the nuclear age. Bewildered and confused, most Pakistanis believed these charges to be exaggerated and manipulated. Others argued that, even if they are true, there is nothing wrong with sharing nuclear technology with friendly countries, as was done by many other states in possession of nuclear weapons (e.g. American and British support for the French nuclear programme).

This book critically examines how and why Pakistan acquired its nuclear weapons, and then delves deeper into the motivations and circumstances of the nuclear proliferation activities of Khans network, with a special focus on Iran, Libya, and North Korea. For the first time in history all the elements of nuclear weapons developmentthe supplier networks, the material, the centrifuge technology and enrichment mechanism, and possibly the warhead designswere outside direct state control at least for part of the time during this roughly sixteen-year proliferation crisis (19872003).

It is important to probe the causes of Pakistans nuclear proliferation. Was it a rogue operation orchestrated by one man, or was it a state-sanctioned operation? If the former, what were its motivational factors? Was it greed, a skewed nationalist agenda, religious beliefs, or an anti-Western/American operation, or possibly a combination of some or all of these? Interestingly, former Pakistan president Pervez Musharraf in his memoirs forcefully argues that the show was completely and entirely A.Q.s and he did it all for money.

In this book I argue that scholars, analysts, and experts who have focused on this issue have so far ignored the larger picturei.e. Pakistans political and security arena and the impact of regional dynamics and international politics on itand have also been too narrowly focused on the personality of Dr A. Q. Khan, which presents just one aspect of the proliferation crisis. Secondly, the research shows that this brand of nuclear proliferation could not have taken place without the political upheaval that Pakistan went through during those years. The civilmilitary tensions within Pakistan, weak and unstable state structures and institutions (political, security related, and judicial), flawed decision-making processes at the highest level (especially in the realm of the nuclear programme), the impact of the Afghan war on Pakistans worldview, the lingering threat from India, and last but not the least the turbulent USPakistan relationship all facilitated, or in some cases enabled, nuclear proliferation. Within this convoluted political and security spectrum, the personal ambitions of some military and political leaders also had a significant role to play. The book also endeavours to show that the existing theories about what precipitated this sharing of nuclear secrets shed little light on the full gamut of circumstances that led to this dangerous situation. Giving away nuclear technology was the final step in an unholy game. It is necessary to try to unravel the thinking behind this operation and also to probe whether all of this was one big operation or a series of developments with different motivations and players. The shadowy workings of an illicit international nuclear smuggling network (with many Europeans playing a central role) serving many countries and clients cannot be ignored either. An important question is whether it was merely a demand and supply issue or whether something more intriguing was taking place.This book thus asks the question:Why did Pakistan acquire nuclear weapons technology, and what caused the nuclear proliferation from Pakistan to Iran, North Korea, and Libya?