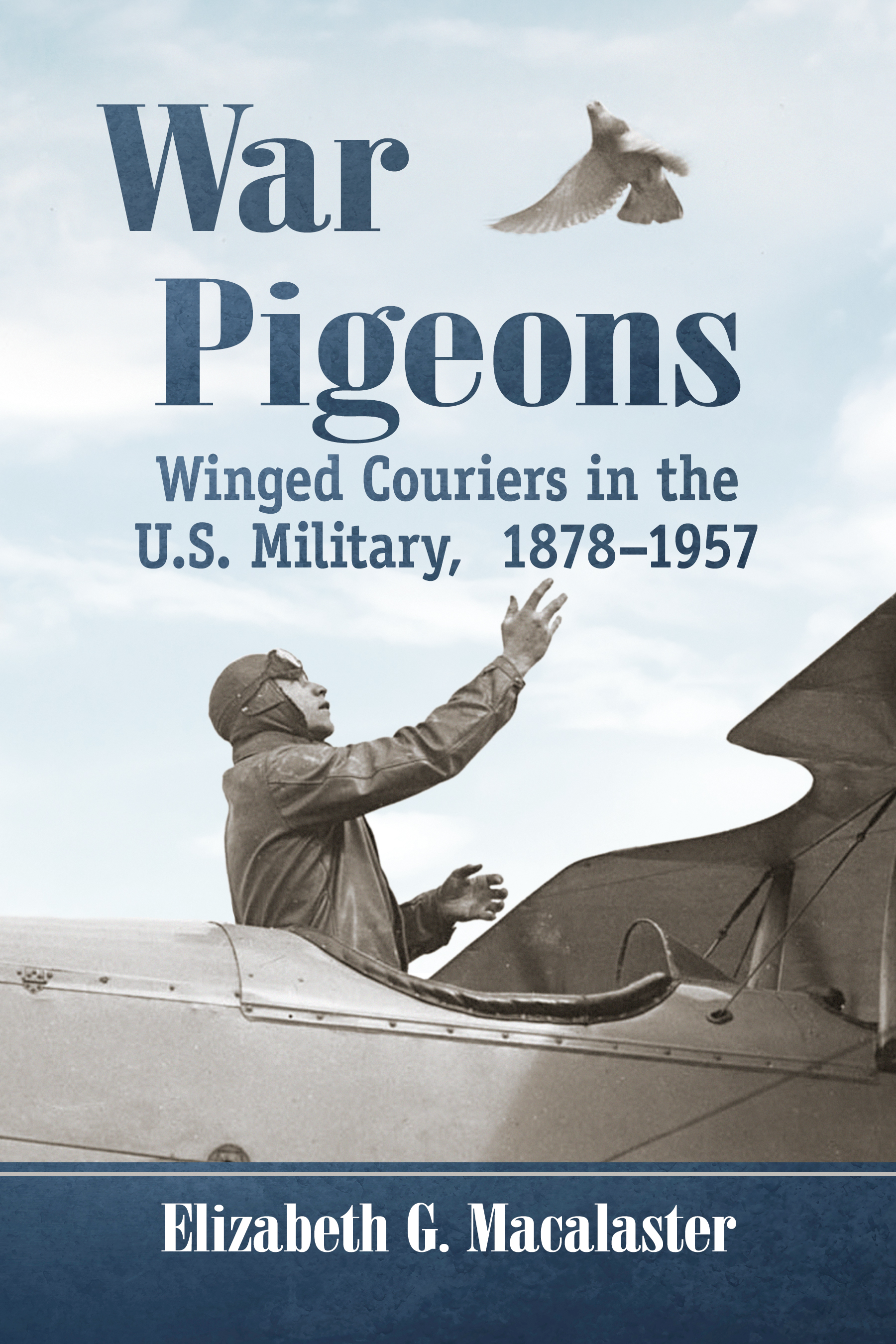

I would like to thank my friends and family for their interest and support over the years during which I explored this somewhat unusual topic of homing pigeons. I know they will never look at a pigeon in the same way again. I especially thank my writers group; Stephanie Greene, Chrysler Szarlan, and Amie Swift; Tom DeRosa, who was a pigeoneer at Fort Monmouth; his good friend Bob Carney, who introduced us; Frank Quatrochi, a pigeoneer during the Korean War; Jennifer Spangler, a journalist and pigeon aficionado with an excellent blog; Deone Roberts at the American Racing Pigeon Union; John Baldwin, pilot; Joe Gluckert, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard historian; military historian Frank Blazich, Jr., for his review of the manuscript; and Ronald Hart, who improved many of the photographs.

A bird of the air shall carry the voice and that which hath wings shall tell the matter. Ecclesiastes 10:20

Prologue : John Silver

In the fall of 1918, more than a million American servicemen took part in the 47-day Meuse-Argonne Offensive of World War I, and more than 400 pigeons served beside them. Tangles of barbed wire, machine gun nests and enemy-filled trenches carved the French countryside. Nothing lived above the ground, and the trenches filled with dead and wounded. Gas attacks occurred on the hour. Machine gun fire and bursting shells shattered the air.

The U.S. Army Signal Corps used mainly field telegraph and telephone to communicate to headquarters and other divisions, but the wires connecting them didnt last long. They were shredded to bits by artillery fire, and wheels and tracks of vehicles. Countless linesmen were killed as they stepped out of the trenches to repair lines. Additional messages were sent with human and dog couriers, but the terrain was heavily forested and cut by deep ravines, making movement treacherous. Under fire and gas attacks, these means of communication proved utterly useless. Only homing pigeons, flying high above the ruin, could reach headquarters with important messages that relayed the status of the allies positions, their needs, their plans.

Earlier that year, in January, a pigeon had hatched in a cold, damp loft not far from the trenches in the Argonne Forest. The gangly and nearly featherless squab grew quickly, and in a few weeks, he was turned over to an experienced handler, a member of the Signal Corps. Rigorous training that included flying home from miles away over rough terrain and through all kinds of weather turned the youngster into a swift soldier pigeon. Fast and assured, the handsome blue-barred cock stood out among the other young birds and became one of the Signal Corps best.

In August, the pigeon was seven months old and left for the front, where the Allies were holding against the Germans. He gained a reputation for acrobatic and fast flying skills that were tested time and time again, as the bird conveyed information from the embattled trenches 25 miles back to headquarters in Rampont.

On September 26, nine American divisions began an assault against the Germans along a 24-mile front from the Argonne Forest to the Meuse River. The goal was to capture a German rail hub at Verdun, thus breaking the rail network that supported the German Army in France and Flanders. Intense fighting caused heavy losses on both sides, but by early October, the U.S. First Army, headed by General John J. Pershing, penetrated the formidable Hindenburg Line, the main line of defense set by the Germans. After this punishing campaign, Pershings men badly needed rest, reorganization, and replacements.

On October 21, the swift, bullet-dodging pigeon was released from the trenches at 2:35 p.m. with a message for headquarters. Just then, the enemy laid down a fierce bombardment. With sinking hearts, the men watched from the trenches as shells burst all around the pigeon. Concussions tossed the bird up and hammered him down toward the ground. It didnt seem possible he would survive, let alone fly. But then, as the soldiers stared in disbelief, the pigeon, struggling to stay aloft in the aftermath of the shells, somehow regained altitude and found his course to Rampont.

The bird made the 25 miles in 25 minutes, despite the flak that surely had hit him. He arrived at his loft in terrible condition. He had been hit in the chest by shrapnel, and a leg was missing, the message capsule hanging by the ligaments of what was left of it. Still, he had gotten the message through.

The blue barred cock was among 442 pigeons at the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The feathered soldiers delivered 402 messages, over distances from 12 to 30 miles. Not a single message was lost.

Weeks of care repaired all but the birds leg. He was named John Silver, after the one-legged pirate in Robert Louis Stevensons Treasure Island. John Silver retired from service in 1921, and took on mascot duty with the U.S. Army Signal Corps, Honolulu, Hawaii. The hero pigeon died December 6, 1935, at the age of 17 years, 11 months.

John Silver was mounted and given to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. He stands in the Early Years Gallery, looking out from among famous airplanes and other war artifacts.

Preface

The extraordinary abilities of homing pigeons like John Silver caught my attention while I was researching stories about women spies for another, earlier book. I came across an article about homing pigeons operating as spies in World War I. A pigeon was outfitted with an aluminum breast harness to which a tiny, time-delayed camera was attached, and then released to fly over landscapes of interest. Spying was done on the wing, the camera snapping photos of the ground below at regular intervals. When the pigeon returned to its loft, the film was developed, and photos reviewed. The Germans used pigeon spies in World War I, and there are claims that the birds lugged cameras for both Allied forces and Axis powers throughout World War II. I was intrigued. How could a pigeon that weighs barely a pound fly straight home through storms, gas, exploding shells, smoke, and gunfire, with a capsule on its leg and sometimes a camera hanging from its body?