Richard Bassett

LAST DAYS IN OLD EUROPE

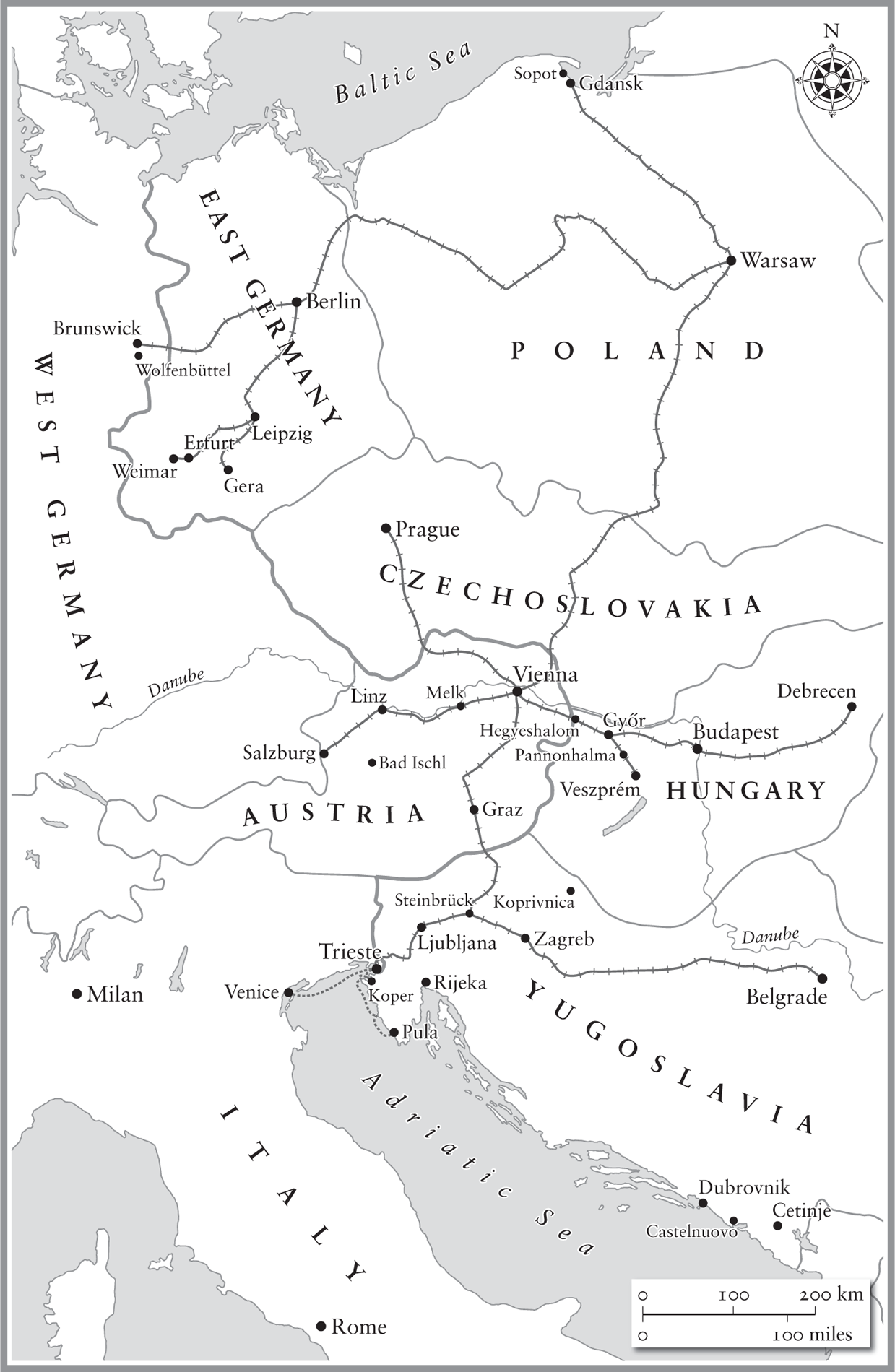

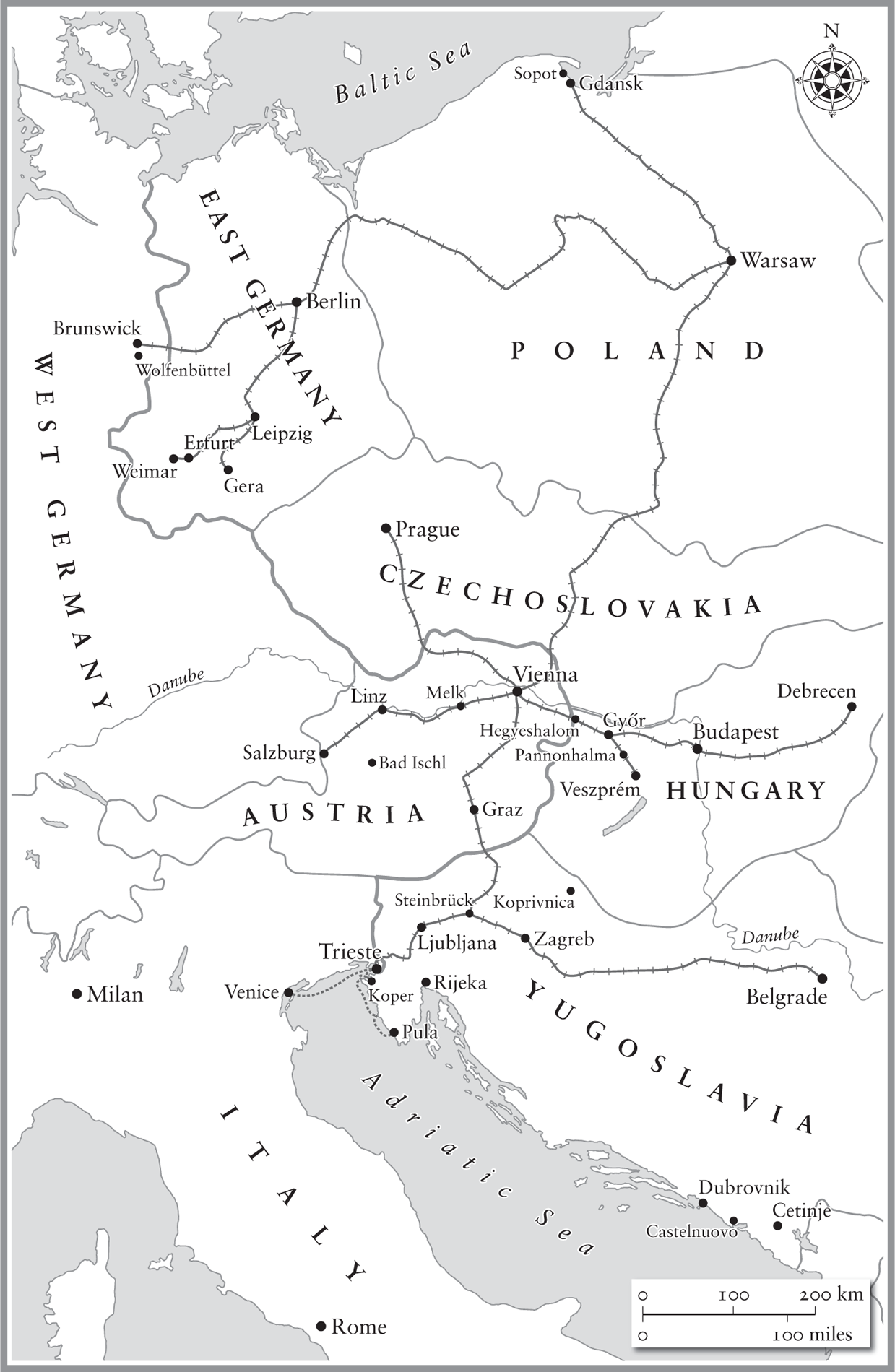

Trieste 79, Vienna 85, Prague 89

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2019

Copyright Richard Bassett, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Ignacia Ruiz

ISBN: 978-0-241-01487-5

In memory of Cornelia Kirpicsenko-Meran

(geb. Grfin Meran)

19632013

and

Reinhold Gayer-Ehrenberg

19502018

nunc Scio quid sit amor: nudis in cotibus illum

aut Rhodope aut Tmaros

Donau in Oesterreich

Mich umwohnet mit glnzendem Aug

Das Volk der Fajaken;

Immer ists Sonntag, es dreht immer

Am Herd sich der Spiess

(Danube in Austria

With their gleaming eyes I am surrounded by

The people of the Phaeacians

For whom the roast-spit ever turns

And for whom it is always Sunday)

Friedrich Schiller, Xenien (1797)

Acknowledgements

This book could not have been written without the kind support and friendship over many years of the people I encountered in Central Europe. Forty-year-old diaries and a fading memory are modest foundations on which to bring personalities back to life, but it was the presence of those personalities in Trieste, Vienna, Warsaw and Prague which made life along and behind the Iron Curtain so memorable and enriching, and I hope I have described them faithfully in these pages. If I have succeeded in conveying the excitement and reward which arises from chance encounters across different generations, then this book will have succeeded in its purpose.

In Vienna, Christopher Wentworth-Stanley, the Tischherr of the English Stammtisch (regulars table) in Hawelkas, played over several decades a much underestimated role in bringing Austrians and English travellers abroad together. In Trieste, Mietta Shamblin discharged the same duty, while in Prague, Victoria Reilly-Spikova and her husband Daniel generously put their handsome villa at the disposal of many other equally fulfilled incontri. I am also grateful to Frank Giles, one of the Sunday Timess most distinguished editors, for reminding me of the circumstances in which a Times foreign correspondent was expected to operate nearly half a century ago. These parameters formed part of an unspoken tradition dutifully and conscientiously discharged by an ever-courteous Times Foreign Desk, then under the capable leadership of Ivan Barnes, a prince among foreign editors.

Given that it was proficiency in playing the French horn which allowed me to first live in and develop my knowledge of Central Europe, it gives me great pleasure to thank here the three horn teachers of my youth: first and foremost, Dr William Salaman, but also his occasional, inspiring successors, Jeffrey Bryant and Timothy Brown. Fifty years later, I have become convinced that much professional achievement, academic or literary, is easily dwarfed by the discipline and diligence needed for the mastery of a musical instrument.

During the early 1980s I was fortunate to enjoy the company in Central Europe of Caroline Mauduit, a gifted watercolourist who frequently reminded me that the visual can complement the literary. In Cambridge I must mention my High Table colleague and friend Michael Perlman, an Honorary Fellow of Christs College. I am indebted to him for his help in tracing in his native Brazil the remarkable story of HM Consul-General Robert Smallbones, whose name I first encountered in Trieste in 1979.

I owe a particular debt to Stuart Proffitt, for encouraging me to attempt to describe the eccentricities of life in Cold War Europe for a generation unfamiliar with that world and bringing his forensic skills to bear on the text. He and his colleagues, including Donald Futers and Ben Sinyor, have polished my prose, removing with tact and precision innumerable infelicities of style and content.

Part of the first section of this book first saw the light of day as a Christmas essay, Trieste 79, published privately by John Sandoe Books for their customers in 2013. A year later, translated by Ada Cerne, it was published also in Italian by the Umberto Saba bookshop of Trieste. I am therefore indebted to Johnny and Boojum de Falbe and Mario Cerne for acting as publishing midwives to this entire project.

Finally I should thank my wife, Emma-Louise, and our children Edmund and Beatrice, who have at times bravely entered the alternative cosmos which was (and is) life in Mitteleuropa.

Salzburg, 18 June 2018

The View from the Molo Audace

TriesteZagrebLjubljanaGraz

There are many shades of sky-blue. In my experience, the most intoxicating is the one which fills the Adriatic sky around Trieste each January after a few days of the Bora wind. The air has a clarity which I have seen equalled only in the highlands of Tibet. From the Molo Audace, simple slabs of Istrian stone stretching out to sea like a pier from the Triestine Riva, the peaks of the Alps, faintly pink, can be glimpsed nearly 70 miles away to the west beyond the lagoons. To the east, the Istrian peninsula, lazy and shimmering in the sunlight, stretches like some reclining voluptuary towards the hazy and distant lands of the Quarnero. It is cold in this bright sunlight but the colours are so vivid one scarcely feels it. Come to Trieste, James Joyce once wrote to a friend, and you will see sun.

It was on such a day in January 1979 that the Simplon-Orient Express dropped me at the foot of the old Sdbahn Terminus after rattling down the cliffs beyond Duino. I was young, tall and thin, conforming to the continental European view of the English stereotype at the time. A heavy midnight-blue barathea coat with wide double-breasted lapels, and an impatient air with the bureaucracy of the luggage carriage, no doubt confirmed the image. Although I had been travelling for more than thirty hours, luggage (sent in advance in those convenient days) was one simple large suitcase. Opening the case the officials found that it contained little to arouse their interest. A pair of pyjamas, some second-hand shirts and collars, a pair of corduroy trousers and a duck-egg green paperback copy of Stephen Spenders memoirs all failed to attract their attention.

In some places, it seems that the circumstances of travel never change. The train will always more or less be a quarter of an hour late, the officials will always be indifferent. Indeed, I might have chosen any time in the previous twenty-five years to effect this arrival in Trieste and I would have been greeted by the same picture of perennial stillness. Trieste had been quiet since the early 1960s. Its status as a minor port of Italy, much disputed by Marshal Titos Communist Yugoslavia in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, had finally been stabilized by an international treaty four years earlier. The Cold War had sealed it from its hinterland and this once great metropolitan port had become, in practice, an enormous museum a museum with very few visitors.