GALAPAGOS AT THE CROSSROADS

GALAPAGOS AT THE CROSSROADS

Pirates, Biologists, Tourists, and Creationists Battle for Darwins Cradle of Evolution

CAROL ANN BASSETT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

Published by the National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

Copyright 2009 Carol Ann Bassett. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

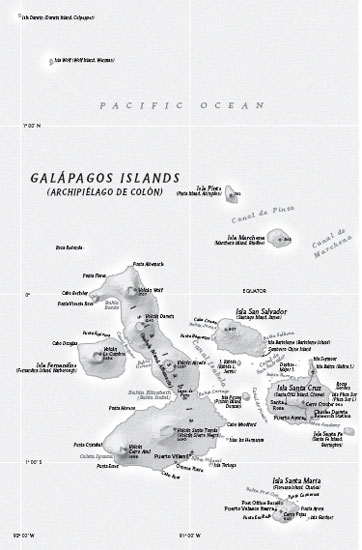

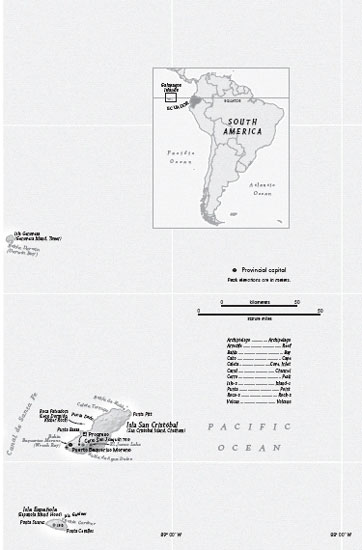

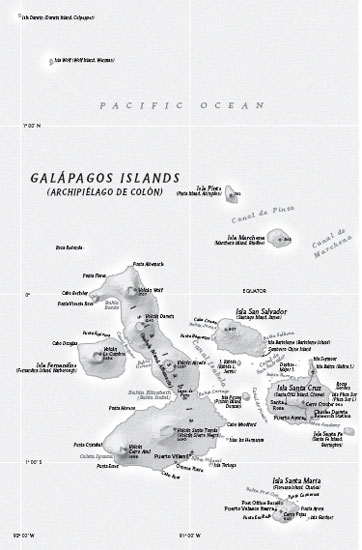

Map copyright 2009 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved.

A Statement of Certainty from Generations (Penguin, 2004), copyright 2004 by Pattiann Rogers. Reprinted by permission of the author.

ISBN: 978-1-4262-0435-7

The National Geographic Society is one of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to increase and diffuse geographic knowledge, the Society works to inspire people to care about the planet. It reaches more than 325 million people worldwide each month through its official journal, National Geographic, and other magazines; National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; music; radio; films; books; DVDs; maps; exhibitions; school publishing programs; interactive media; and merchandise. National Geographic has funded more than 9,000 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program combating geographic illiteracy. For more information, visit nationalgeographic.com.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463) or write to the following address:

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at www.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

09/RRDC/1

To the children of the Galpagos.

May you teach your parents well.

CONTENTS

Introduction

I n the time of the gara, when cold Pacific currents flow north from Antarctica, then west along the Equator, an eerie mist shrouds the Galpagos Islands like a veil. In Spanish, gara means persistent light rain, and to the early explorers, pirates, and whalers who once passed through the archipelago, this ephemeral haze could be both seductive and deadly: The illusion of water called out like the enchanting Sirens of Greek mythology. Charles Darwin wrote in his field journal in September 1835: The main evil under which these islands suffer is the scarcity of water. What Darwin and those before him did not understand was that the Galpagos had survived precisely because the lack of fresh water had rendered the islands uninhabitable to humans. But to the strange and lovely denizens dispersed to these islands by wind, water, and on rafts of organic debris, life had taken a different course. Land species that gained a foothold on these young volcanic islands adapted to whatever food was available, and they evolved in ways unimaginable. Marine species thrived in the plankton-rich waters, including penguins washed ashore by the Humboldt Current.

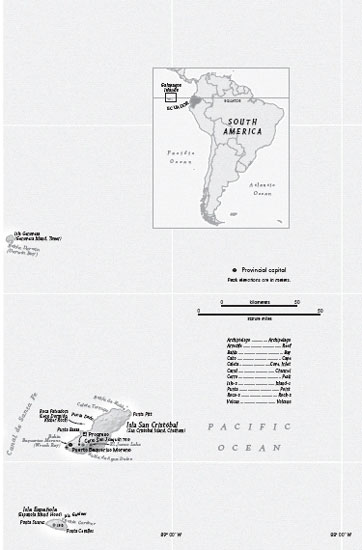

The Galpagos remained isolated until their accidental discovery in 1535 when Fray Toms de Berlanga, the Bishop of Panama, and his crew, on a mission to what is now Peru, were caught in a dead calm and drifted westward on the ocean currents. Berlanga described the islands as dross, worthless, and rejoiced when the trade winds returned to free his ship from this haunting inferno. In time, those who followed would learn to adapt to this volcanic landscape straddling the Equator, just as had the bizarre life-forms that evolved there throughout the millennia: giant land tortoises that can survive more than 150 years; marine iguanas able to hold their breath under water for up to an hour; cormorants that no longer need wings to fly; vampire finches that survive on the blood of masked boobies; daisies that have morphed into giant trees.

The Galpagos Islands and their unusual denizens, part of the nation of Ecuador since 1832, stand at a critical crossroadson a collision course with 21st-century values driving tourism and immigration, and with invasive species that prey on the very life-forms that make the Galpagos special. In 2007 the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the islands an endangered World Heritage site, and scientists, conservationists, and Galapagueos are working to protect the archipelago before its too late.

Today, about 35,000 colonists call the Galpagos home, and more arrive every day, despite new laws intended to limit immigration. The population growth is 6 percent per year, compared with only 2 percent on the Ecuadorian mainland; demographers predict the population could well surpass 50,000 in the next few decades. Ninety-seven percent of the land mass of the islands is protected as a national park; the other 3 percent includes the towns and private land. Yet this 3 percent is where some of the worst problems originate. As the influx of settlers grows and the towns begin straddling the parks boundaries, social, economic, and environmental problems have multiplied. Invasive species brought to the islands over the centuries by colonists and tourists have wreaked havoc throughout the archipelago. Goats, burros, pigs, dogs, cats, and rats have decimated the wildlife and vegetation on several islands, including Isabela, where about 100,000 feral goats turned the verdant hills into a desert and nearly obliterated the giant land tortoises that lived on Volcn Alcedo. While eradication work has succeeded in eliminating those intruders on Isabela and other islands, it could take years before some islands return to their natural state, if ever.

I first visited the Galpagos in 1990 as a young journalist on assignment for a national magazine. Like most visitors, I felt that I was entering a primordial dreamscape where time and space had stood still. From the shore of Floreana Island, I watched a school of spotted eagle rays wing through the waves like butterflies. In the darkness of night, bottlenose dolphins frolicked beside our tour boat, their fins sparkling with bioluminescenceliving light from microscopic organisms. I quickly realized that I had come to Las Encantadas (the Enchanted Islands), as the early Spanish explorers called the archipelago. In the skies above North Seymour Island male frigate birds floated on thermals, their throats puffed out like giant red balloons to attract mates. But what struck me most was the baby sea lion on Santiago Island that trailed me like a puppy and sniffed at my shoes, not knowing what to make of me. As I gazed one day out to sea I spotted a lone sea turtle plowing through the waves like a dark leviathan. Perhaps this is what Darwin saw when he wrote that in the Galpagos, both in time and space, we seem to be brought near to that great factthe mystery of mysteriesthe first appearance of new beings on this earth.