ENVOI THE DARWIN ARCHIPELAGO

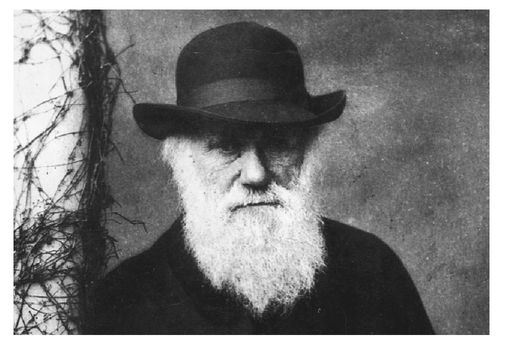

When Charles Darwin moved to Down House in 1842 the population of England was fifteen million and London, the largest city in the world, had some two million inhabitants. At the time of his death, forty years later, the number of Londoners had doubled and the capitals fringes were creeping towards his retreat. The city has multiplied by four times since then and his home has become a museum. It sits in a well-preserved enclave that pretends to be a village but is in fact part of the London Borough of Bromley. A few segments of countryside nearby have been preserved (and the tangled bank, the microcosm of life referred to at the end of The Origin, is almost unaltered) but the landscape around Down House has become suburban at best. A glance across the famous Sandwalk reveals the tailfins of planes parked a few hundred metres away. Biggin Hill Airport was a Battle of Britain fighter base whose pilots claimed to have shot down more than a thousand aircraft. Now the place is the most popular light aviation centre in England and its annual air fair attracts a hundred thousand visitors. A lot has changed in the Kentish countryside since Charles Darwin walked across what has become an oil-stained strip of tarmac.

Many other places associated with the great man - and many of his subjects, from apes to earthworms and from insectivorous plants to Homo sapiens himself - have been transformed since his demise. That would be a surprise to the patriarch of Down House. Darwin looked at the past to understand the present. He scarcely considered what the future might bring, for in his view evolution was so slow, and flesh so stable, that no real changes in the world of life were to be expected for many generations to come. In the long term, no doubt, the outlook was bleak: as he wrote in a letter to his old friend Joseph Hooker: I quite agree how humiliating the slow progress of man is, but every one has his own pet horror, and this slow progress and even personal annihilation sinks in my mind into insignificance compared with the idea or rather I presume certainty of the sun some day cooling and we all freezing. To think of the progress of millions of years, with every continent swarming with good and enlightened men, all ending in this, and with probably no fresh start until this our planetary system has again been converted into red-hot gas. Sic transit gloria mundi, with a vengeance.

A moment of hindsight on his two hundredth birthday shows that he was badly out in his timing of the coming apocalypse, at least when it came to biology. Every continent is indeed swarming with men, but progress (if such it is) has not been slow, but meteoric. A great deal has happened in the evolutionary instant since 1809. In the next two centuries, plants, animals and people will see an upheaval greater than anything experienced for thousands of years. For most plants and animals the prospect of biological annihilation is far closer than the certainty of the heat death of the universe.

In the last few weeks of his voyage, in July 1836, the young explorer had a brief vision of what lay ahead. The Beagle dropped anchor at St Helena, halfway between Africa and South America. The island, first occupied by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, is among the most isolated places in the world. Darwin was delighted by it: a hundred square kilometres of volcanic mountain rose like a huge black castle from the ocean. He admired the English, or rather Welsh, character of the scenery and noted to his surprise that St Helenas vegetation, too, had a British air, with gorse, blackberries, willows and other imports, supplemented by a variety of species from Australia. Over seven hundred plants had been described - but nine out of ten were invaders. They had driven the original inhabitants to extinction or to refuges high in the mountains. A sweep of thin pasture near the coast was known to locals as the Great Wood - which is what it had been until a hundred years before, when the trees were felled and herds of goats and hogs consumed their seedlings and killed the forest. Plagues of rats and cats had come and gone as they ate themselves to extinction. On his first day ashore, he found the dead shells of nine species of land-shells of a very peculiar form (one of the few mentions of snails in his entire oeuvre) and - in an early hint of evolution - noted that specimens of a certain species differ as a marked variety from others of the same species picked up a few kilometres away. All those molluscs apart from one had been wiped out and replaced by the common brown snail of English gardens.

Two centuries or thereabouts after his visit, life on St Helena is worse. The island once had forty-nine unique species of flowering plant and thirteen of fern. Seven have been driven to destruction since the arrival of the Portuguese, two survive in cultivation and many more are on the edge. The last St Helena Olive died of mould in 1994. Parts of the tree-fern forest of the high mountains - still in robust health at the time of the Beagle - remain, but other unique habitats visited by Darwin, such as the dry gumwood, have gone and of the ebony thickets just two bushes remain. The islands giant earwig (at eight centimetres the worlds largest), its giant ground beetle and the St Helena dragonfly, all common in the 1830s, have not been seen for years and Darwins snail of peculiar form is now reduced to a population of no more than a few hundred. The St Helena Petrel is extinct and a solitary endemic feathered creature, the Wire Bird, is left. That too is under threat.

Three months after the farewell to St Helena, the naturalists diary records that we made the shores of England; and at Falmouth I left the Beagle, having lived on board the good little vessel nearly five years. His account of the expedition ends with a spirited enjoinder to all naturalists to take all chances and to start on travels by land if possible, if otherwise on a long voyage. Charles Darwin never left British shores again.

He had no need to, for, as this book has shown, the plain landscapes of his own country gave him the raw material needed for a life filled with science. Darwins fifty years of work on his homelands worms, hops, dogs and barnacles changed biology for ever. Since then the British Isles have provided another useful lesson for students of wild Nature, for their modest archipelago is a microcosm of the global upheavals that have taken place since the naturalist came home.

Bartholomews Gazetteer of the British Isles, in its edition published just after the great naturalists death in 1882, describes Kent, the Garden of England, as a paradise: The soil is varied and highly cultivated... All classes of cereals and root produce are abundant, as is also fruit of choice quality and more hops are grown in Kent than in all the rest of England. The woods are extensive... Fishing is extensively prosecuted... of which the oyster beds are especially famous.

A lot has changed since then. The local farms bring in half what they did even a decade ago. The oysters are almost gone and the salmon fishery of the Thames Estuary, which fed the apprentices of London with such abundance that they refused to eat fish more than once a week, has collapsed. Bucolic pursuits have been replaced by that invaluable product, services, which accounts for three-quarters of the countys contribution to the nations wealth. Kent is a dormitory of London and London has become a staging post for the world. The flow of people, power and cash has carved up its landscape with motorways, rail links and webs of power lines. The oast houses that once stored hops have become commuter homes and the hops themselves - the raw material of so many experiments - cover a fraction of the fields he knew. So far, the Great Wen has been kept in part at bay by the Green Belt, but plans for a Thames Gateway mean that yet more of the Garden of England will soon be a bland suburb.