Contents

Guide

also by Pam Houston

A Little More About Me

Contents May Have Shifted

Sight Hound

Waltzing the Cat

Cowboys Are My Weakness

Copyright 2019 by Pam Houston

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Fearn Cutler de Vicq

Production manager: Beth Steidle

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Houston, Pam, author.

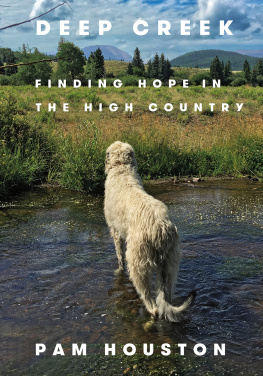

Title: Deep Creek : finding hope in the high country / Pam Houston.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018037969 | ISBN 9780393241020 (hardcover)

Classification: LCC PS3558.O8725 A6 2019 | DDC 814/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037969

ISBN: 978-0-39328-549-9 (ebk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For

Emma, Kyle, Becky, Dustin, Meghan,

Jessica, Kyle (#2) and Maggie,

who tended the ranch while I was away,

and who let themselves be mothered.

And for Mike Blakeman,

who has given me one more big beautiful reason to come home.

None of the single original claims was capable

of providing a living for a family, but land is fascinating and

more or less magnetic and has always had a value and probably

always will. It is a feeling of stability and security to own

a piece of land. You always feel like you have a home,

no matter how humble.

John LaFont,

The Homesteaders of the Upper Rio Grande

What elegy is, not loss but opposition.

C. D. Wright

Contents

DEEP CREEK

Introduction:

Some Kind of Calling

W hen I look out my kitchen window, I see a horseshoe of snow-covered peaks, all of them higher than 12,000 feet above sea level. I see my old barnold enough to have started to lean a littleand the low-ceilinged homesteaders cabin, which has so much space between the logs now that the mice dont even have to duck to crawl through. I see the big stand of aspen ready to leaf out at the back of the property, ringing the small but reliable wetland, and the pasture, greening in earnest, and the bluebirds, just returned, flitting from post to post. I see Isaac and Simon, my bonded pair of young donkey jacks pulling on opposite ends of a tricolor lead rope I got from a gaucho in Patagonia. I see Jordan and Natasha, my Icelandic ewes nibbling on the grass inside the goose pen, keeping their eyes on Lance and L.C., this years lambs. I see two elderly horses glad for the warm spring day, glad to have made it through another winter of 30 below zero, and whiteout blizzards, of 60 mph winds, of short days and long frozen nights and coyotes made fearless by hunger. Deseo is twenty-seven and Roanys over thirty, and one of the things that means is I have been here a very long time.

Its hard for anybody to put their finger on the moment when life changes from being something that is nearly all in front of you to something that happened while your attention was elsewhere. I bought this ranch in 1993. I was thirty-one years old, and it seems to me now I knew practically nothing about anything. My first book, Cowboys Are My Weakness, had just come out, and for the first time ever I had a little bit of money. It was $21,000more money than I had ever imagined havingand when my agent said, Dont spend it all on hiking boots, I took her advice as seriously as any I have ever received.

I had no job, no place to live except my North Face VE 24 tent (which was my preferred housing anyhow), nine-tenths of a Ph.D., and all I knew about ownership was it was good if all of your belongings fit into the back of your vehicle, which in my case they did. A lemon yellow Toyota Corolla. Everything, including the dog.

I drove the whole American West that summer, giving readings in small mountain towns and looking for a place to call home. I started in San Francisco and headed northPoint Reyes, Tomales, Elk, Mendocino. I crossed into Oregon and looked at land in Ashland, Eugene and Corvallis. All I knew about real estate was you were supposed to put 20 percent down, which set my spending ceiling at exactly $105,000. I had no idea people often lied to real estate agents about their circumstances, and sometimes the agents lied back. I had $21,000, a book that had been unexpectedly successful, no job and not three pages of a new book to rub together. I understand now that in a certain way, I was as free at that moment as I had ever been, and would ever be again. I came absolutely clean with everybody.

I checked out Bellingham, and all the little towns on the road to Mount Rainier, and then headed over the pass into the Eastern Cascades, where I put a little earnest money down on a place in Winthrop, Washington. Forty-four acres on a gentle hill with an old apple orchard and a small cabin. I worked my way over to Sandpoint, Idaho, and Bozeman, Montana, still looking, still unsure.

But when I drove through Colorado, a place I had ski-bummed between college and grad school, I remembered how much Id loved it here. In those days I had lived in the Fraser Valley, at a commune of tarpaper shacks and converted school buses called Grandma Millers New Horizons. I lived for three winters in a sheepherders trailer named the African Queen. The twenty or so alternatives who lived at Grandmas shared an outhouse, a composting toilet and a bathhouse. From late December to early February it often got down to 35 below. I was working as a tourist bus driver by day and a dishwasher at Fred and Sophies steakhouse by night. I would collect every strip of steak fat the diners would leave behind on their plates in a giant white Tupperware next to my station. When I got off work, I would go home and feed all that steak fat to my dog, Jackson. If I packed the little woodstove just right, it would burn for exactly two and a half hours. I would don my union suit, my snow pants, my down coat, hat and mittens, and get into my five-below-rated North Face sleeping bag. I would invite Jackson up on top of the pile that had me at the bottom of it, and he would metabolize steak fat all night, emitting not an insignificant number of BTUs.

It was my writer friends Robert Boswell and Antonya Nelson who first told me about Creede. When you drive into town, the sign at the outskirts boasts 586 Nice Folks and 17 Soreheads. It was, and still is, the kind of place where if you happen to be in town for a couple of days poking around, someone will invite you to a wedding. That September, the guy who owned the hardware store was getting ready to marry his longtime sweetheart, and instead of sending out invitations they just put an ad in the weekly Creede Miner , so everybody would know to come by.

At the wedding, I met three women who owned their own businesses: Jenny Inge who made jewelry out of silver and horsehair, Victoria Beecher who sold flowers and plants, and Max McClure who had opened a coffee shop and was making Creede residents their very first lattes.