Table of Contents

ALSO BY MICHAEL DANTONIO

Forever Blue: The True Story of Walter OMalley, Baseballs Most Controversial Owner, and the Dodgers of Brooklyn and Los Angeles

A Ball, a Dog, and a Monkey: 1957The Space Race Begins

Hershey: Milton S. Hersheys Extraordinary Life of Wealth,

Empire, and Utopian Dreams

The State Boys Rebellion

Tour 72: Nicklaus, Palmer, Player, and Trevino:

The Story of One Great Season

Mosquito: The Story of Mans Deadliest Foe (with Andrew Spielman)

Tin Cup Dreams: A Long Shot Makes It on the PGA Tour

Atomic Harvest: Hanford and the Lethal Toll of Americas Nuclear Arsenal

Heaven on Earth: Dispatches from Americas Spiritual Frontier

Fall from Grace: The Failed Crusade of the Christian Right

For the girl who shares tea with me every night

Dr. Optimist is the finest chap in the names directory of any city or country. He and I have been life-long friends and boon companions.

Just try a course of his treatment. It will work wonders.

And this doctor charges no fees!

SIR THOMAS LIPTON

ONE

Glasgow

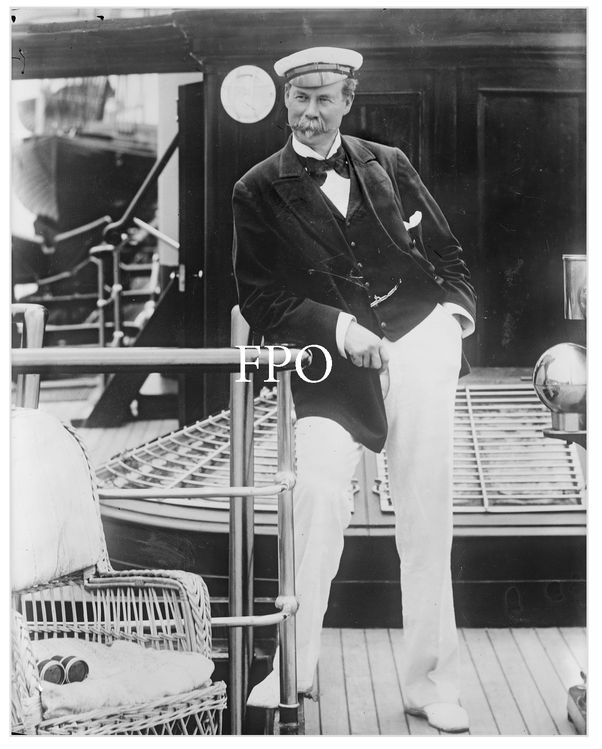

The yachting cap with the black leather bill was a kind of trademark, just like the floppy polka-dot bow tie, the white mustache, and the inch-square patch of whiskers under his lip. For thirty years, on occasions when he met the public, he had placed the cap on his balding head, adjusted it with a little tug, and become in an instant the man who called himself The Great Lipton.

Tall and ruddy-faced, Sir Thomas Lipton had proved that a poor, undereducated boy could conquer the world of business and rise to fame as an international sportsman. His friends included the rich, the famous, the powerful, and the royal. His successes and failuressome quite spectacularhad been announced a thousand times in the press on both sides of the Atlantic and made him one of the most recognized figures in the world.

Even children knew Liptons story, and in the summer of 1930 they came running from every direction when they heard he was going to give out free cookies and chocolate at his warehouse in the Anderston district of Glasgow. These children of the Great Depression, raised under a cloud of deprivation, understood that Sir Thomas would stay until every last child got a treat. He had done it before.

On that Friday, July 4, 1930, the queue on Lancefield Street began forming in the morning and eventually stretched for a cobbled quarter mile, all the way down to the dock at the River Clyde. Sons and daughters of shipbuilders, sailors, factory workers, and maids waited patiently until a fancy private car wheeled down from busy Stobcross Street and stopped at the curb. When Lipton emerged, unfolding his old body to stand tall and square in an immaculate suit, cheers rippled off the soot-stained buildings and echoed into the air. He replied with a smile that deepened the crowsfeet that framed his sparkling blue eyes.

At age eighty-two, Lipton had lost much of what had been familiar and reliable to him. Once one of the most eligible bachelors in the world, he no longer attracted the throngs of women who had loitered in hotel lobbies hoping to catch his eye. Most of the vast business empire that bore his namethe plantations, factories, warehouses, and chain of grocery shopswas now controlled by a board of directors. Nearly all of his longtime associates and friends, including Whiskey Tom Dewar, Andrew Carnegie, King Edward VII, and Queen Alexandra, were dead. He had no close family and, as far as anyone knew, no lovers. But he still possessed an unbroken connection to the working-class districts of Glasgow.

With its smoky air and overcrowded tenements, Anderston was a tough neighborhood. Gangs controlled the streets at night, and life for the law-abiding was a matter of hard work and struggle. It was the same as it had been when Lipton started there in business and began to manufacture himself, story by story, and image by image. The cap, bow tie, and mustache were decorative elements of the Lipton myth, which was relentlessly cheerful and positive. But the real man was reflected in the facessome dirty and wary, others eager and hopefulthat lined up on the pavement. On the eve of his last great adventure he spent hours greeting them and handing out gift boxes like a summertime Santa Claus. In return he collected their gratitude and heard the sound of his past in their voices.

As a Glasgow boy, Tommy Lipton had received what he called a liberal education in the give-and-take, the rough-and-tumble of life. With its enormous productivity, the city of Liptons youth all but vibrated with creative energy. Even the grime in the streets seemed fertile, feeding the ambitions, hopes, and dreams of the working class who labored in dangerous and dirty industries that operated right next to tenements and houses. The most noxious were the foundries, like Dixons ironworks, where open-pit furnaces glowed so brightly through the night that people called the place The Blazes. Glasgows mills produced a million tons of pig iron annually. On drizzly days the acrid smoke from their fires covered everything with a black film. On blue-sky days the smoke was carried by the prevailing winds, billowing over the mills, factories, docks, and sprawling shipyards of the area called Clydeside.

Glasgow made almost everything from locomotives to calico, but the great ships built at local yards were the ultimate symbols of the citys status as the industrial center of the far-flung British Empire. Strong, graceful, and powered by the latest in steam technology, Glasgow ships sailed on every ocean in the world and in rivers and lakes from Australia to America. They were so superior that the term Clyde-built became synonymous with quality. The ships established the citys identity as a hub of international trade. They brought cotton, timber, leaf tobacco, and other raw materials and departed with iron, steel, textiles, leather, and heavy machinery. They also enabled the easy flow of people in and out of the city. Scots departed from the Clyde for adventures in the British Empire or to resettle in America. Others, especially poor Irish families fleeing famine and turmoil, came to Glasgow looking for jobs in factories, mills, and foundries.

Thomas Liptons parents had lived in County Fermanagh in rural Northern Ireland, and then in County Down. After years of poverty, and the deaths of two young children, they fled in 1847later called Black 47as famine killed people all around them. In Glasgow, Thomas Lipton, Sr., found work in a box factory while the familyincluding his pregnant wife, Frances, a son, John, and daughters named Frances and Margarettook shelter in a slum district called the Gorbals. There narrow, shadowy lanes called wynds cut between four-story tenements made of local sandstone that had been blackened by pollution. The wynds were barely wide enough for a pushcart, and their gutters often overflowed with sewage. A resident walking down one of these dark alleys would occasionally come upon a little courtyard, called a close, which would be as cramped and confining as the name suggests. A typical close was both a playground for children and a dump for all sorts of waste. The communal pump found in a close often delivered water teeming with pathogens, like cholera bacteria, washed down into the water table by falling rain.