A LSO BY J ASON D E P ARLE

American Dream: Three Women, Ten Kids, and a Nations Drive to End Welfare

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Jason DeParle

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: DeParle, Jason, author.

Title: A good provider is one who leaves : one family and migration in the 21st century / Jason DeParle.

Description: [New York, N.Y.] : Viking, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019011071 (print) | LCCN 2019017314 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984877758 (ebook) | ISBN 9780670785926 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Comodas, Rosalie. | Comodas, RosalieFamily. | FilipinosUnited StatesBiography. | ImmigrantsUnited StatesBiography. | FilipinosEmploymentForeign countries. | Foreign workers, FilipinoUnited States. | United StatesEmigration and immigrationHistory21st century. | Emigration and immigrationHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC E184.F4 (ebook) | LCC E184.F4 D47 2019 (print) | DDC 305.899/21dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019011071

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Version_2

For my parents,

James and Joan DeParle

Home has its charms, and native land has its charms, but hunger, oppression and destitution will dissolve these charms and send men in search of new countries and new homes.

F REDE RICK D OUGLASS , 1869

A good provider is one who leaves.

P EACHY P ORTAGANA S ALAZAR , 2006

CONTENTS

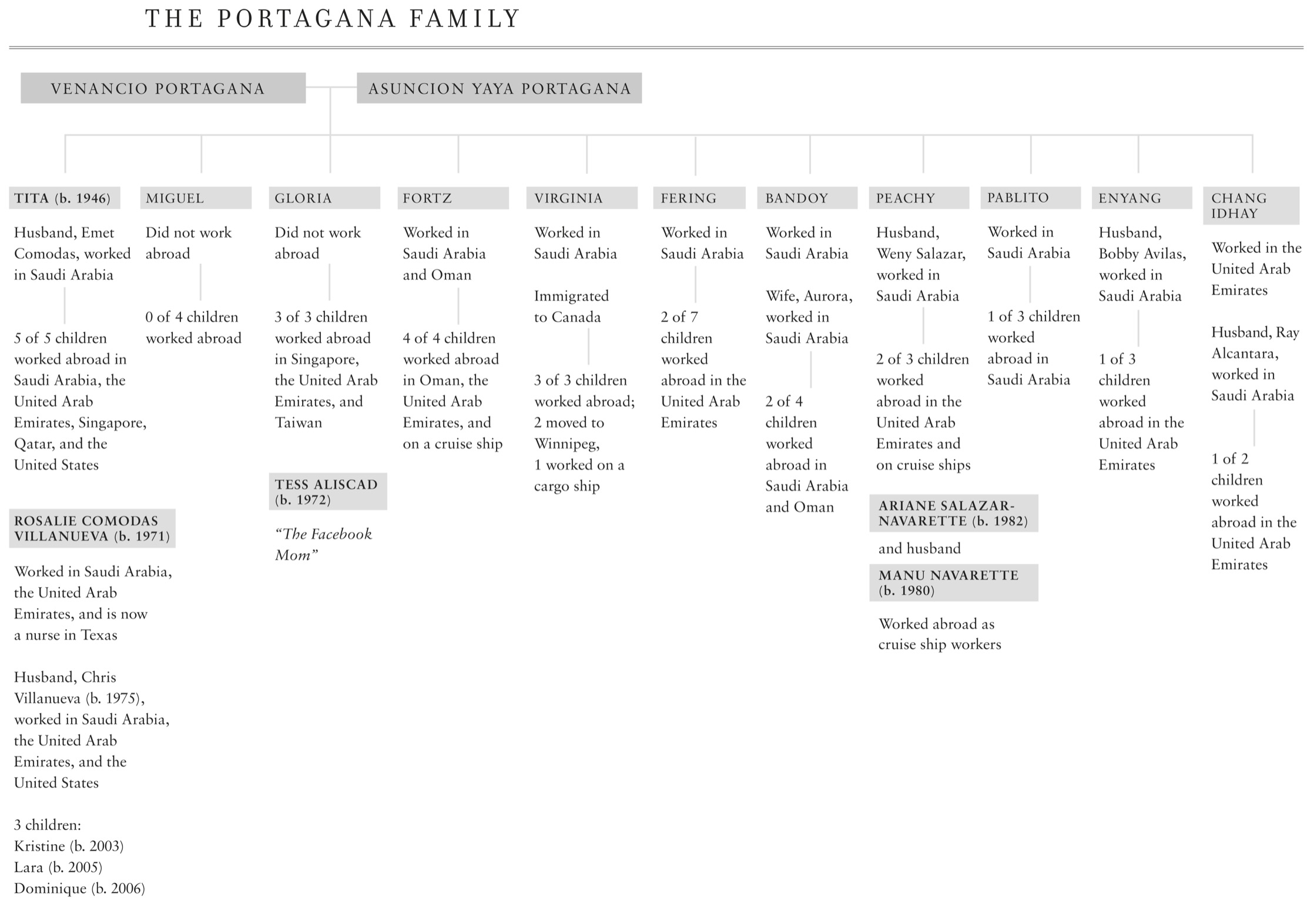

MAIN CHARACTERS:

Tita Portagana Comodas and Emet Comodas

Rosalie Comodas Villanueva, Chris Villanueva, and their children Kristine, Lara, and Dominique

Tess Aliscad

Ariane Salazar-Navarette and Manu Navarette

FIRST GENERATION: 9 of 11 Portagana siblings worked abroador had a spouse who didin Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Canada

SECOND GENERATION: 24 of 41 cousins worked abroad in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Qatar, Singapore, Taiwan, Canada, the United States, and on cruise ships

PROLOGUE

Finding Jesus in the Slums

Thirty years ago, I was a young reporter in Manila with an interest in shantytowns, the warrens of scrap-wood shacks that covered a third of the city and much of the developing world. I called the Philippiness most famous nun, who lived in a slum called Leveriza. Though I didnt say so, I was hoping she would help me move in.

Sister Christine Tan was a friend of the new president, Cory Aquino, and busy on a commission rewriting the constitution.

Call me back in a few months, she snapped.

Hoping for a quicker audience, I explained that I worked with another nun in her order. Apparently, they werent friends. Thats a mistake! she said. Meet me tomorrow morning, outside the Manila Zoo.

Raised in affluence, educated in the United States, Sister Christine had gained her renown as a critic of Ferdinand Marcos, the American-backed dictator who had proclaimed martial law in 1972 and plundered the country with the help of his shoe-happy wife, Imelda. I hate their deceitfulness, their sham, their greed, their avarice, their lies, the deliberate trouncing of our rights and the burying of our souls, she once said. The Vatican had told her to tone things down. The police had threatened arrest. Sister Christine had defied them all and gone off to find Jesus in the slums. At fifty-six, she had a smooth, grandmotherly face, which made her look gentle, though she wasnt.

Are you CIA?... You wouldnt tell me if you were, would you? she began. When she called herself anti-imperialist, it sounded like an accusation.

The poor are magnificent people, unlike the rich, she said, but boarding in Leveriza wouldnt work. Most of the shanties lacked toilets, and Americans cant live without them. A host would feel obligated to serve pricey food. Id be a burden. She denounced the United States for keeping military bases in the Philippines, then suddenly waved a hand above her head. Thats all up here, meaning her views of American policy. Somehow, we have to build links between the First World and the Third World. If I returned in a few days, shed see what she could do.

Sunk into a mudflat near Manila Bay, Leveriza held fifteen thousand people in a labyrinth of alleys behind the whitewashed walls of one of Imeldas old beautification campaigns. Children played beside listing shacks. Women squatted over tubs of laundry. Roosters crowed. Sanitation mostly meant flying saucers, bundles of waste wrapped in newspaper and flung in the surrounding canals.

I figured that Sister Christine would use the time before my return to approach a potential host or two. Instead, she led me into the maze and auctioned me off on the spot. I knew just enough Tagalog to realize our first prospect was aghast. Hindi pwede, Sister! Its not possible. The second candidate smiled more but ducked as rapidly. The third was too astonished to respond. Tita Comodas was forty years old and sitting at her window in an old housedress, selling sugar and eggs. A scruffy American looking to rent floor space had the appeal of a biblical plague.

Her thin patience exhausted, Sister Christine left. If you dont want him, pass him on to someone else. And dont cook him anything specialif he gets sick, too bad!

I dont know who was more frightened, Tita or me. Neighborhood entertainment was scarce; we drew a crowd.

Ask him if he eats rice!

Ask him if he knows how to use a spoon!

Ask him if he wants to marry a Filipina!

Tita had a boisterous neighbor who fed her questions and whooped at the answers. But Tita struggled to see the humorafter all, it was her house. The reasons to decline were many. Her husband was working in Saudi Arabia... she was busy raising five kids... she already had two relatives sleeping on the floor... her English was limited and my Tagalog was worse... Who knew what problems a strange foreigner might cause? Then she surrendered to what she took as Sister Christines request and said I could move in. I stayed on and off for eight months and made a lifelong friend.

The eldest of eleven children raised in a farm family, she had quit school after sixth grade and moved to Manila as a teenager to work in a factory. Marriage and children followed, with home a series of Leveriza hovels, each as forlorn as the last. Her husband, Emet, had hustled a job cleaning the pool at a government sports complex and held it for nearly two decades. On the spectrum of Filipino poverty, that alone marked him as a man of modest fortune. But a monthly salary of $50 wasnt enough to keep his family fed. Their eldest daughter had a congenital heart defect that turned her lips blue and fingernails black and who needed care that he couldnt afford. After years of worrying over her frail physique, Emet had dropped to his knees and asked God for a decision: take her or let him have her. God had answered in a mysterious way. Soon after, Emet got an offer to clean pools in Saudi Arabia. He would make ten times his Manila wage but live five thousand miles away in an Islamic autocracy when stories of abused laborers were rife. He accepted on the spot. By the time I arrived, years later, his daughter had more medicine and the shanty had a toilet.