Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR STEPHEN

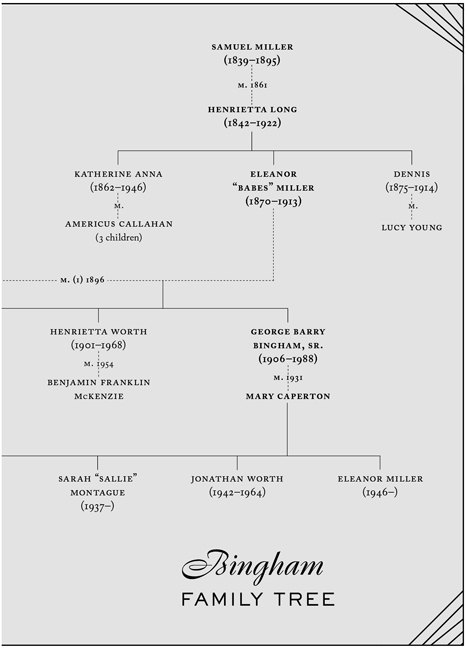

The surest way to make a child curious about an ancestor is never to discuss her. And when it came to Henrietta Bingham, my great-aunt with the most great-aunt-like name, there was much to be curious about. Born in 1901, she came of age amid tragedy and enormous wealth, and spent much of her twenties and thirties ripping through the Jazz Age like a character in an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. There were parties, music, great quantities of alcohol, and, on both sides of the Atlantic, loverslots of them, men and women, but far more women than men. In Henriettas time, that took courage. Later there would be mental breakdowns, scandals, and a decline no one talked about. Within our family, charity meant silence when it came to Henrietta.

Long-ago forebears who defy propriety and cause wringing of hands can feel as thrilling and dramatic as fairy-tale figures, but even for those who knew Henrietta, she was an almost magical physical presence with a muse-like influence, an irresistible way of being with others.

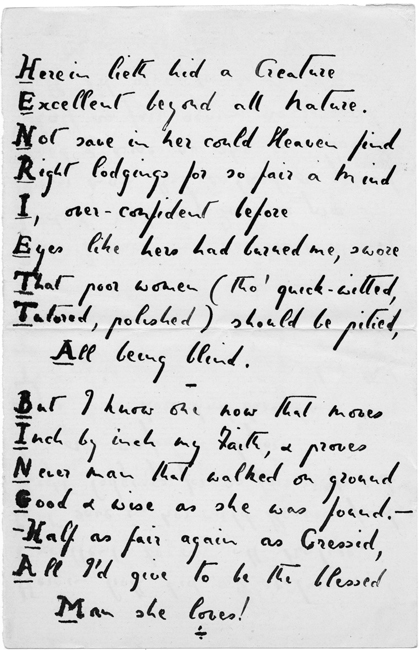

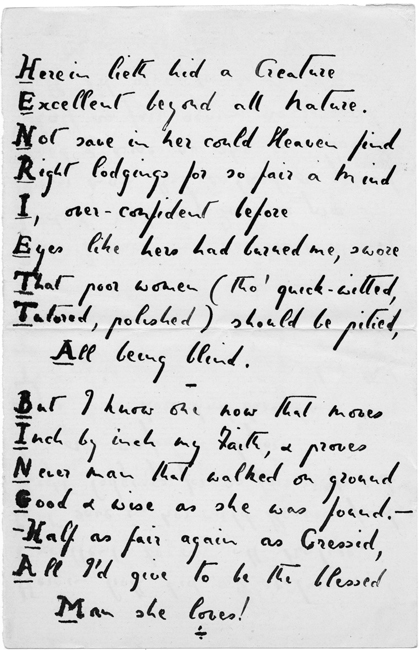

They talked about her eyes. People had never seen eyes like Henriettas, purple eyes with tangled lashes. In the absence of color photographs, their arresting hue would be lost to history were it not for her lovers attempts to capture them in language. The actor and producer John Houseman, Orson Welless collaborator and the winner of an Academy Award, called them violet-blue. Brilliantly blue, offered the novelist David Garnett. But it was not just their color. She looks the memory of her eyes into you, a poet explained. They were fascinating with her coquettish lashesthe eyes of a too-wise little girl. Henriettas hair was jet, her face oval, her skin cream-white, and one companion declared she should preach, her voice is so divine. The painter Dora Carrington called her a Giotto Madonna.

* * *

One London night in 1923, at a party in the studio of the artist Duncan Grant, twenty-two-year-old Henrietta mixed deliciously unfamiliar cocktails, played the mandolin, and sang. Her voice, soft, low, faintly husky, moved over Water Boya chain-gang tune later recorded by Paul Robeson and Odettaexuding extraordinary warmth.

There aint no sweat boy

Thats on this mountain

That run like mine boy,

That run like mine.

A lament about exploitation became a seductive performance that helped establish her position as a Kentucky princess in the Bloomsbury Group, the high-minded bohemians who coalesced around the novelist Virginia Woolf and her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. (Henrietta was one of very few Americans to penetrate that elite set, where conventions of marriage, art, and domestic life were often flagrantly disregarded.) Her singing violated cultural, racial, and sexual boundaries, and was just the sort of transgression she delighted in making during the Jazz Age years. But Henrietta did more than assume the accoutrements of 1920s youth culture. The Charleston and the Black Bottom, saxophones, stride piano, whiskey jugs and blues women, all then emerging from marginalized African American communities, were for her points of deep identification, sources of rapture, and proof that genius could overcome discrimination and injustice. This privileged white southern debutante taught herself to play the saxophone and promoted black performers, some of whom became her friends. It is no coincidence that these art forms bristled with eroticized energy, for Henriettas greatest connection with the spirit of the 1920s and 1930s was the way her youth blazed with sex. The passage of time usually drains the past of desire and its fulfillment, but if Henrietta had an essence, this was it.

Her provocative acts succeeded because they drew on something deep in her, an emotional sweat that showed in the panic attacks and destructive behavior she spent years untangling in the consulting room of an eminent London psychoanalyst, Ernest Jones. Sigmund Freuds pioneering and controversial theory of the unconscious mind revolutionized twentieth-century ideas about the individual and societyand, of course, sexand undergoing psychoanalysis offered hope of self-understanding and acceptance. At the same time, arousing others distracted Henrietta from her problems. It was deeply satisfyingand she was incredibly good at it, too. That London night in 1923, she blasted into the hearts of Dora Carrington and a sculptor named Stephen Tomlin. Like many before and many after, they couldnt drive her from their minds. They were caught, as I would be nearly a century after them, in her irresistibility.

* * *

Henrietta began as a curiosity to me, a historian who had moved home to Kentucky to raise a family. She died in 1968 when I was threeI never knew her. But my husband and I appreciated her unconventionality and liked her unfashionable Victorian name, so we gave it to our newborn daughter. Only then did my startled father tell me that to him Henrietta was a mess, an embarrassment, a three-dollar bill. His sisters remembered her as fascinating but dangerous. To be like Henrietta, one of them told me, would mean to never be married, never have children, and be a lesbian. But her name was again among the living and despite such judgments, relatives, family friends, and people I barely knew wanted to talk about the earlier Henrietta. They came forward with photographs, bejeweled cigarette cases, bits of gossip, a few crumbling letters, and hints about where more Henriettiana might be found.

So began my pursuit of one of the countless outsiders who populate the past. If we try hard enough, can we call them back, give them form beyond mere names and dates and whispers? I found Henrietta listed in the indexes of memoirs and biographies and scholarly volumes. Visits to archives across the United States and in England unearthed discoveries, some marginal, some mother lodes. I mined quite a few of these repositories before heeding the advice my father had offered in 2006, shortly before he died.

You might want to look up in the attic. I think theres an old trunk of Henriettas.

The attic was in my former home, a Georgian mansion overlooking the Ohio River on the outskirts of Louisville. Henrietta was seventeen when her millionaire father acquired the place with a legacy from Americas richest woman, his second wife. An earlier, hasty look in the trunk marked H.W.B. had revealed a hodgepodge of old clothes and shoes. To figure out Henriettas magnetism, I needed moreprimarily letters and diariesso I wasnt in a hurry to comb through the steamer chest. But on a raw January morning in 2009, I went up to the gable storeroom on the southeast side of the house. Lining the trunk were oranged London newspapers from 1937she had apparently packed it in England during her fathers last months as Franklin D. Roosevelts ambassador to Britain. I tried on a pair of woven driving gloves and turned over a hand-tinted photograph of the mother who perished when Henrietta was twelve. There were puzzling items of finely made womens underwear marked with the initials H.T.C., and, thrillingly, monogrammed tennis clothes belonging to Helen Jacobs, the Martina Navratilova of the 1930s, with whom Henrietta became, in the parlance of the day, close friends for a number of years.