PART ONE

WEIGHING IN

B ITING INTO A BIG, FAT CHOCOLATE E ASTER EGG . Thats my first conscious memory of life. And today, nearly 75 years later, I can close my eyes and still recall the sticky sweetness and intoxicating aroma as I contentedly munched that sumptuous treat, which was a gift from my godfather.

The momentous occasion took place in the spring of 1939 at my uncle Tonys house, not far from my childhood home on Hook Avenue in the heart of the Junction, an ethnic working-class neighborhood on the west side of Toronto.

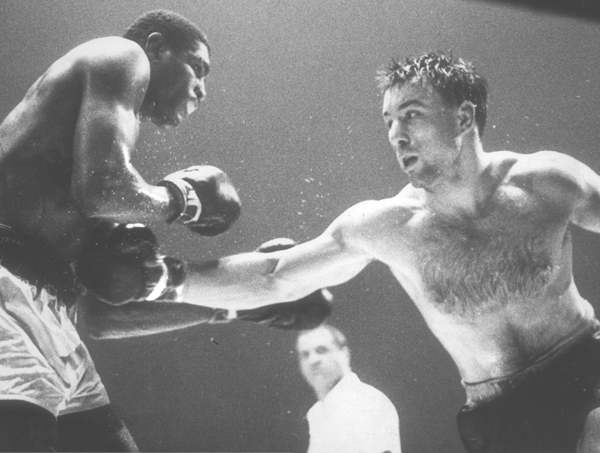

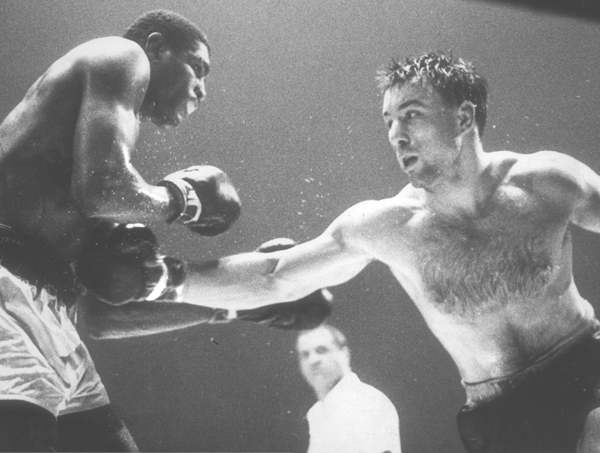

Fast-forward four decades and a few miles east, to St. Lawrence Market at the corner of Jarvis and Front streets. Its December 11, 1978. That night I climbed through the ropes for the 93rd time as a professional fighter, aiming to do what Id done 63 times previously: make the other guy see the black lights. Thats how old-timers described what it feels like to drift into unconsciousness.

On this occasion, the other guy was George Jerome, a plodding, nondescript logging-camp cook from Vancouver with a record of 11115. That he was ranked the No. 1 challenger for the Canadian heavyweight title that Id owned, almost continuously, since 1958 only underscored how low the sport had sunk in a country that has produced some of boxings all-time greatsguys like George Dixon, Sam Langford, Tommy Burns and Johnny Coulon.

The 2,000 fans jamming the joint couldnt have cared less who was in the opposite corner; they were there for the blood sacrifice. That crowd was a far cry from the 15,000-plus who once routinely watched me headline at Madison Square Garden, and the $7,500 payday was a fraction of what Id gotten to slug it out with the likes of Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman just a few years earlier, but I was too keyed up to think about the past. I was 41 years old and doing the only thing I ever wanted to do, the one thing I was born to do. I didnt care who was standing in front of me; I just wanted to whack him hard enough to make him see those black lights.

That was my rush. Thats what I lived for.

It was even better than that chocolate Easter egg.

Jerome didnt put up much of a fight. Midway through the second round I hurt him against the ropes with a three-punch combination, then backed him up with a left hook to the ribs. As he dropped his hands in anticipation of another body shot, I ripped another left upstairs that split his forehead like a melon, slicing open a two-inch gash above his right eye. Within seconds his face was a mask of blood, and the crowd went nuts. At the end of the round, the ring doctor examined the wound and ordered the fight stopped.

Jeromes corner didnt complain. If he had come out again, he might have needed a blood transfusion.

Did I feel bad for the guy? Not a bit. It was just another night at the office. The only thing I was concerned about was that my beautiful 11-year-old daughter, Vanessa, was in the crowd. Shed never seen her daddy work before, and she looked a little scared. I could only imagine what was going through her head.

I didnt know it at the time, but that would be my last fight.

Jerome was the 35th opponent I dispatched in three rounds or less and my 64th knockout in 73 pro victoriesa KO-per-win ratio of 87.6 per cent. It wasnt until 1997, when I was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in Los Angeles, that my buddy, Edmonton Sun columnist Murray Greig, pointed out that Bob Fitzsimmons (89.5), George Foreman (89.4) and Mike Tyson (88.1) were the only lineal world heavyweight champions up to that time with a higher ratio.

But nobody talked about my punching. I got far more ink during my career for having a great chin and for never being knocked down, but for a long time I thought those were negative accolades. Until my first fight with Ali in 1966, nobody mentioned my chin, but afterward it was big news. After I retired, some writers declared I had the best chin in boxing history. If thats true, I chalk it up to three things: being born with a short neck, training to absorb punishment (like a linebacker in football), and chewing a lot of bubble gum to strengthen my jaw muscles.

Im prouder of the fact that, on the way to compiling a record of 73182, I had more knockouts than both Jack Dempsey (47) and Joe Louis (51), and my 64 KOs are more than Rocky Marciano, Ali, Frazier or Tyson had total fights.

Never kissing the canvas will undoubtedly be my lasting legacy in boxing, but there was a lot more to my career than that. Today, most people think I was a tough guy who took a good rap, which is fine. But I was a much better defensive fighter than I ever got credit for. I didnt get hit with half the punches people think I did. If that were true, Id be walking around on my heels today. Nobodys that tough.

Ill be remembered as a guy who fought the best of his time, beat a lot of them and lost to some others. I was a world-ranked contender for the better part of two decades, during the reigns of some of the greatest heavyweight champions in history. I knocked on their door a few times, but was I satisfied with that? Hell, no! If youve never been champion of the world, you can never be 100 per cent satisfied.

A fighter always thinks he couldve done better than he did, and Im no different. Theres always a gnawing feeling that I might have become a world champ; theres a piece of me that always feels kind of incomplete. Still, I did better than most guys. I won the Canadian amateur title at 17, then held the national professional championship for almost 20 years. I was ranked No. 2 in the world at one time; not many can say that.

Was it worth all the blood and the sweat and heartaches?

Absolutely. Besides, what else could I have become? With education and the right breaks, anyone can aspire to become a doctor or a lawyerbut you have to know real poverty to want to earn your living as a fighter. During much of my career, poverty was a constant companion.