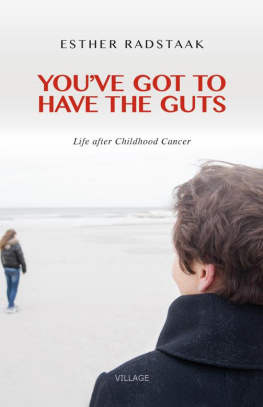

Youve Got to Have the Guts

Youve Got to Have the Guts

Life after Childhood Cancer

Esther Radstaak

isbn 9789461851192 paperback

isbn 9789461851208 ebook

Original Dutch title: Je moet het durven

1st print november 2015

Design: Eric Jan van Dorp

Translation: Aviva Dassen, Karin Wouters, Jacob Gibbons

Cover photo: Irene Hoekstra

Published by Village, an imprint of VanDorp Publishers

Postbox 42

3956 ZR Leersum

The Netherlands

Copyright2015 Village / VanDorp Publishers

Copyright2015 Esther Radstaak

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ESTHER RADSTAAK

YOUVE G OT T O HAVE THE GUTS

Life afte r Childhood Cancer

VILLAGE

All revenues from this book will be donated to the

VOKK, the Dutch Association for Childhood Cancer

As a television news reporter, I rarely experience a personal story that actually touches me. I speak to victims people who were duped or discriminated against on a regular basis, but normally I can shake it off quite easily. From a reporters perspective, its always nice to find a person who is actually involved in the story. That is how I met Esther; I had to report on the consequences of childhood cancer and a large national scientific study that was launched during that time. I visited Esther one afternoon in her house in Ede, and was greeted by a cute dog, delicious home- made cake, and a big garden.

Esther is a childhood cancer survivor, and she was introduced to me by her treatment specialist. I noticed straight away how tense she was, but I also saw her willpower to show herself to the outside world in both her vulnerability and strength. That is what truly struck me that afternoon. She was a person with a past, a very clear mission, and an unbelievable passion, who dared and wanted to share her story. Go ahead and try to do the same, exposing yourself in front of millions of people.

That afternoon, we both felt that we got along quite well. That is a big advantage when wanting to make a good documentary, but such chemistry is by no means a guarantee that everything would work out. After we were done, we both felt positive about the interview, and that is how we parted our ways. I phoned her the day after to express my admiration, and to ask for her response after seeing the broadcast. She was surprised, and immediately indicated that she wanted to write a book about it. In all honesty,

I had my reservations at the time. She kept in touch through text and told me about her progress. And here we are: that book is in your hands right now.

Beautifully written from the point of view of a twelve-year- old, and later when transformed into the perspective of an adult, this book is accessible and remarkably detailed. I dont doubt for a second that her many years of therapy have contributed to the fact that she remembers so much from before, and that she is able to commit her story to paper.

In all honesty, I think everyone who has been through a traumatic experience will be able to relate to this book. It provides an insight in the experiences of a teenager who suffers from a horrible disease. Additionally, the role of the parents during the disease process is described poignantly and can be of great help to others.

Esther, many congratulations on finishing this accessible book. In your own words, you have indeed come full circle.

- Dutch TV reporter Theo Verbruggen

Contents

It seemed so idyllic. My husband Kees, our daughter Marloes, and I we lived a good life together. We had a beautiful home, I liked my job, and we were spared any financial concern. An outsider would look at our family with envy, but what they could not see is that all of those jealousy-inspiring living conditions were lost on me. On the inside I felt like a zombie, and a deeply unhappy one. Every day I was faced with the sensation of looking at myself from a distance, and feeling like I had no say in what happened to me.

This also came with its physical repercussions. It became more and more difficult to eat, and, without choosing to, I started to lose weight. Youre overworked, my mother told me, but I denied it violently. I knew what burnouts felt like. This was different, but I couldnt quite put a finger on what exactly it was.

This estrangement of myself and the desire to escape it became so great that I wanted to die. After all Id been through, after all those years of fighting, I knew I should be happy to be alive, but the truth was that I didnt feel that way. At the most unexpected moments, bits and pieces of my oncological past continued to surface. It was as if the sick little girl of times past wanted to let me hear her voice sometimes.

When my scale indicated a meagre fifty kilos, I knew what I had to do. I sent an email to my previous oncologist, with whom I kept in touch, and told her that I wanted to move up my checkup. I knew I wasnt doing well, but I couldnt put into words what I was going through, let alone explain it to others.

I walked into the hospital with legs like jelly. This was the hospital where I used to be treated, and where I had a job at the time. I hoped not to run into people I knew, so I didnt have to explain why I wasnt at work. The door of my oncologists practice room was open, and when she saw me she motioned me to come inside. She seemed startled when she saw what was left of me and how skinny I was. I couldnt do much more than stutter.

Im at my wits end I should be grateful to be alive, right? Then why am I bursting with guilt for still being here when others are not? I stole two years of my parents and sisters lives, because everything revolved around me. Am I going insane?

I hardly dared to look at her and nearly drowned in my own sorrow. The specialists response was unexpectedly fierce.

Youre not crazy at all. You really have got to stop trying to please others at your own expense. Your parents decided to have children, so they should be there for you, especially when youre seriously ill. That is what parenthood is, you know. How could you possibly think that you are to blame for being sick for two years?

I wasnt used to her forcefulness, but it did me some good.

Theres another thing, she added. I hope youve got the time today, because the psychologist of the childrens clinic is waiting on you. I forwarded your email to him straight away. Ill skip the physical tests for now, since theyre not too important.

Thats where our fixed ritual ended. When I was young, every time after sampling blood, the oncologist would draw a smiley face on the white plaster and made hairs out of the cotton ball under it. I was too old for that now.

In the waiting room, I seated myself amongst the young cancer patients. I used to be able to deal with this quite well, but on that day I couldnt. Their sadness floored me, and the parents powerlessness was unbearable. The assistant at the desk saw me growing more upset, and guided me to an empty consultation room.

Ill ask the psychologist if she can come in a bit sooner, she promised me, leaving me very thankful for her empathy.

It was Friday, June 11, 2004. The psychologist found the notes she took fourteen years ago. They were notes of a couple of conversations wed had after my granddad passed away. She wasnt surprised that I was back. One of the possible causes of my problems, she thought, was post-traumatic stress disorder.

At that time the extent of the term PTSD was unfamiliar to me. The thing that mainly got through to me was that this woman, a professional, ensured me that the way I felt was perfectly normal, and that Im not the only one to feel this way. Filled with hope, I wanted to make an appointment for a follow-up session, but I had to deal with a setback straight away. The psychologist is not a specialist in the field of EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing, an effective treatment to process traumatic experiences), so she would not be able to give me the treatment I needed. She promised to find someone who would, but that meant that I had to completely bare my soul to a new psychologist. I hated that.

Next page