This book is a work of memory. The experiences I write about are told from my perspective. Much has been left out, but nothing has been added. Some names have been changed.

I come from a place that seems to nurture two kinds of people: those who stay and those who leave. I grew up in a family of stayers, but I left. And now, as far as I know, I am the only person in the entire history of Freeville, New York (aside from my own grandfather), to leavebut then return again.

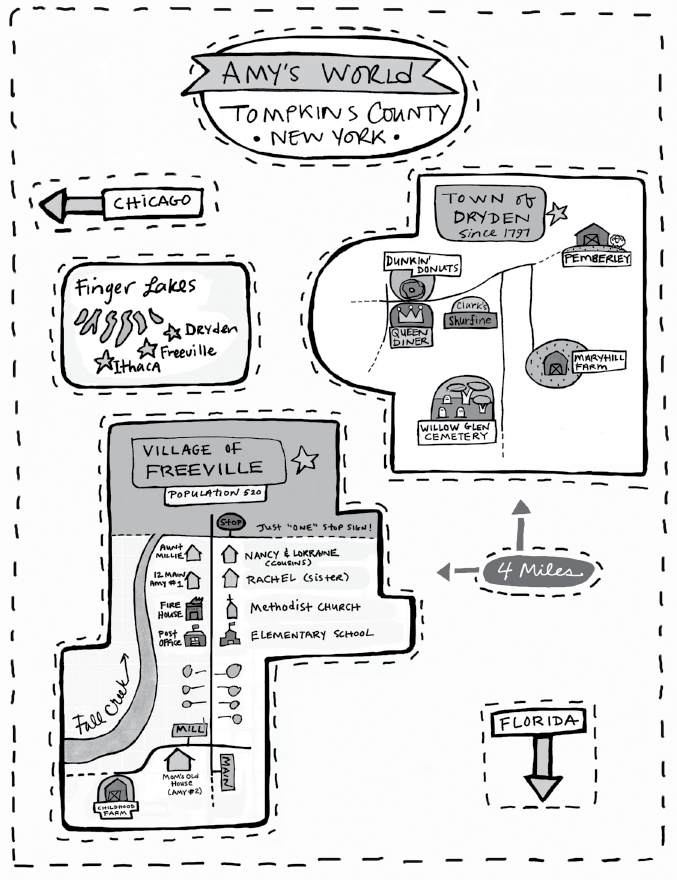

Like me, my grandfather Albert grew up in Freeville, moved to Washington, DC, for his career, and moved back to Freeville later in life. My grandfather died in the house in which he was bornour family homestead on Main Streetwhere his daughter, my ninety-year-old aunt Millie, currently lives. As I write this, I am sitting in my own little house on Main Street, twenty feet away. Looking out my window, I can see my elderly aunt toddling around in her kitchen.

Freeville is a good place to be from. The village of 520 people has one stop sign marking the end of tree-lined Main Street. Children ride their bikes to the village school, and in the summer you still see kids carrying fishing poles as they walk to the old Mill Dam to fish. On summer evenings, people sit on their porches and slap at the mosquitoes that swarm the lights.

Thats what a lot of people probably think about when they remember their childhood in Freeville. But they do their remembering mainly from Florida, where everybody who leaves seems to wind up. The Freeville-to-Florida diaspora is fed by a pipeline powered by low wages and high taxes. Our former citizens are also blown south by the blizzards that rip through the region from Halloween to Mothers Day. Freeville lies near Ithaca, New York, on an axis between the small cities of Binghamton and Syracuse (ranked by the Farmers Almanac as being the fourth- and fifth-worst weather cities in the United States).

Even if you have the constitution to shovel your driveway for five months every year, there is also the cloud cover to contend with. The sky hangs low; much of the time it is gray and gloomy. My mother, Jane, used to call this a lowery sky, and while she always claimed to love it, she was alone in her affection for those dusky months, when the suns low passage in the sky tended to be completely obscured by clouds. When it finally set, you arrived at the realization that it was probably time for supper.

My family has called this place home since 1790, when the first of my mothers family, the Genungs, pushed west after farming for over a centuryfirst in Flushing, Queens, and then in New Jersey. My far-off ancestor was given a land grant in the frontier of the Finger Lakes district in exchange for fighting in the Revolutionary War. The area where he settled and where our family took root and grew is rugged, hilly, and interrupted by spectacular glens, streams, lakes, and waterfalls. Then there are the Finger Lakesglorious narrow glacial gashes that create miles of shoreline and spectacular vistas. Surely when he arrived in our county with his two oxen, my ancestor felt some ancient Scottish tug in his cells. I know I do.

We who live here are granted four sharp and thrilling seasons (although spring and summer tend to be brief), landscape to make your heart swell, andwhen the weather breaks our way and the clouds parta glorious sky that inspires a full-bodied gratitude just to be alive. On a rare sunny day, you basically want to tear your clothes off and run down the street, crazily rejoicing. We natives do not behave this way, however. Overall, we are a tamped-down, noneffusive people with New Englandstyle reserve and a belief in the power of bootstraps to pull oneself upas well as the utility of good fences to make good neighbors. We are not huggers, nor lovers of nonsense or drama. We do not suffer fools, gladly or otherwise.

When I was a senior in high school, I told my mother that I wanted to go to Cornell University, just twelve miles away. She responded that of all of her (four) children, I was the one who most needed to leave. Temperamentally, I am a gamboling baby goat pastured with strong and steady draft horses. My mother might have detected a restlessness inherited from my father, who was always on the move but never satisfied. I followed her directive and left home for college in Massachusetts when I was seventeen. After that, I moved from city to city as my life and career dictated, but I always came back home to Freeville. I brought my daughter Emily home for every Christmas and Easter, and for the bulk of many summers. Those years when I lived in New York City and Washington (four and seven hours away, respectively), I would drive back to Freeville for Halloween, just so I could see the trick-or-treaters begging for candy up and down Main Street. I chose to move home permanently when I was forty-eight years old, and it is likely that I will stay here in Freeville for the rest of my life.

During the 1930s, my home countyTompkins Countywas declared officially part of Appalachia. Its poverty seems Appalachian, with rusty trailers and sway-backed farmhouses and sad little settlements ringing the larger and more prosperous county seat of Ithaca.

Freeville is one of the villages that prospective Cornell University students drive through on their way to its sprawling campus in Ithaca. Aside from our handsome brick school next to the old white Methodist church and our busy post office across the street, most of the houses along Main Street are in need of a fresh coat of paint. Two of these houses were half painted a shade of strawberry red by an itinerant crew of housepainter brothers several years back. The brothers took off with their down payment and never returned to finish the job. Will these houses be fully painted before they fall down? Unless the brothers return as suddenly as they disappeared, it seems unlikely.