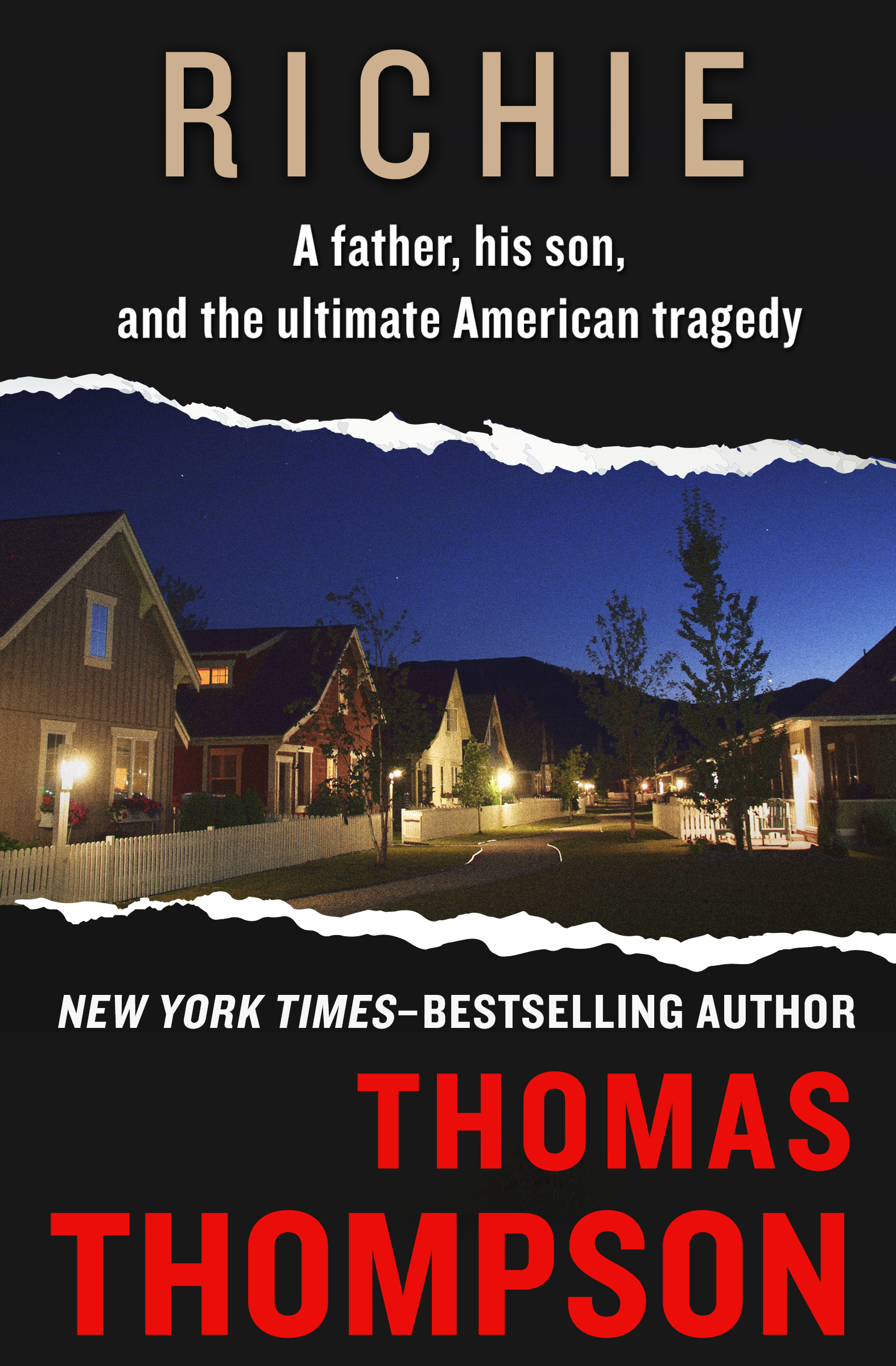

Richie

Thomas Thompson

Many people contributed to the making of this book. Among those who gave support, cooperation, and information are Charles Sopkin, Steve Gelman, Janine Coyle, Ralph Graves, Stephen Sheppard, Robert Lantz, Bill Wise, several docters who asked to remain anonymous, and numerous parents and young people of East Meadow, New York. And special thanks to various members of the Diener family.

For rarely are sons similar to their fathers. Most are worse. But a few are better.

HOMER , The Odyssey.

Epilogue as Prologue

On a cold bleak day at the beginning of March, 1972, the burial, or at least the service of burial, was quickly done. The minister in attendance had not known the deceased, only what he had learned from the surviving family, and what he had read in the newspapers. Thus his prayers were brief and impersonal and almost lost in the winds that whipped the mourners huddled in the enormous government cemetery on Long Island.

It is perhaps the largest graveyard in the world. According to a spokesman, certainly it is the most active as far as interment is concerned. More than 180,000 people, all servicemen and their families, rest here beneath the small and precise white tombstones. So regimented are the rows of the dead that the fantasy of a military parade comes immediately to mind, legions of dead stretching to the horizon.

Because there are forty-five services each weekday, rites are scheduled on an efficient printed worksheet twenty-five minutes apart. To accommodate the great number waiting to be buried, the cemetery conducts what it calls curbside burials, which are a fast and convenient ceremony, one both efficient and considerate to the bereaved. A striped tent on wheels is set up in advance near a curb and parking area. The cortege is directed to the tent as it enters the main gate. Upon reaching the curb, the hearse is parked a few feet from the tent. Pallbearers and mortuary attendants have but a step or two to guide the coffin inside the tent, where it rests on a small platform. If there are few flowers for this man, then there are always some left over from the man before. The striped tent is almost festive.

This is not the actual gravesite. Not until hours after the mourners have left do the busy gravediggers come around to the deserted bier, and, as the cemetery spokesman puts it, transport the remains to the actual hole in the ground.

Under the striped tent, Carol Diener bore up well, her eyes reddened from five days of weeping but hidden behind large, shell-rimmed dark glasses. Those about her, however, were openly crying. A decided clash of generations mourned with her. Nearest stood her husband Georges alliessolid, middle-class, clad in somber cloth coats. The men were clean-shaven, the women dabbing at their eyes with good linen handkerchiefs or moving a hand to stop the wind from blowing their hair, which had been in curlers all night to look well for thisor anyoccasion.

A few feet behind the older people, as if an invisible fence held them in check, were the youngthe friends of Richietheir tinted glasses more for decor than as an aid to vision, their colors bright, for they were not yet old enough, or even inclined, to wear mourning garments. They drew back, not looking at the coffin, moving their eyes instead to the skies, watching the gray clouds move in from the sea.

As the Methodist minister finished his last prayer, his black gown flapping in the wind, the sun vanished and grayness settled over the cemetery. The mourners hurried into their cars. The older people moved carefully for the exit in serious and functional vehicles. The young piled into brightly painted automobiles, one with a psychedelic sunburst on its trunk, cars that seemed impatient to burst from this place of death and be on the road where rock music could erase the coldness around them.

That afternoon, the gravediggers carried the casket to its actual site. It was lowered into a thirty-foot-long trench and placed end to end with the other dead of the day. When the earth was put back and smoothed, it began to snow. The carillon broadcast an electronic taps. Whiteness covered the rawness of the long trench, wrapping the forty-four other caskets put into the ground that day with a blanket of order. All was clean, all was conformity. The older people would have liked it.

PART ONE

George and Carol

Chapter One

Forty-three years before the snow fell to end the day at the Long Island cemetery, George Diener was born, in Brooklyn, in a nation about to slip into the Depression. He was a beautiful baby, with fair hair from the German ancestors on his fathers side, and the spirit and good humor of the Irish from his mother. There is an early photograph, taken when George was three or four, showing him in a neatly laundered sunsuit, sitting on an outcropped rock in the middle of a swift stream in upstate New York. His face is a canvas of wonder and happiness, yet possessed of a curious mask of privacy, of introspection alien to a boy that young. It seemed to say, leave me alone.

On the day that photograph was taken, his mother had to cry out several times, George! Get out of there! Youd sit on that rock all day long if Id let you! George tested her discipline a few more minutes, watching the small trout flash by, feeling the icy water splash his legs, before he reluctantly waded out, got into the borrowed car, and endured the long drive back to Brooklyn.

There were few such outings in Georges young life because his was a city family struggling to pay rent and keep food on the table. His territory had definite limits. Its borders were the Catholic Church and the towering nuns who both fascinated and frightened him; his sister, older by three years, who said everything she did was right and everything he did was wrong; and the crowded apartment in the back of the malt and hops store that his father owned on Seneca Avenue. For one dollar the elder Diener would sell a small can of malt and usually throw in free hops for the customer to make five gallons of legal home-brewed beer during Prohibition.

Early in Georges life, his father lost the store and, like millions of other Americans, embarked on a desperate search for any work at all. For a time he conducted a trolley car, then he repaired Model T Fords, finally he found work with securityan important word, that one, the father hammered home to his sonas a mail clerk with Texaco. Georges world expanded. With German parsimony and management, the Dieners arranged to buy a two-family house for $8,500 on Autumn Avenue in the melting-pot Cypress Hills section of Brooklyn. The street was tree-lined, the neighborsa dentist, a fireman, a shoe salesman, a dress cuttersat on their front porches at night and gossiped across to one another, children ran everywhere with freedom. And the children are clean! rejoiced Mrs. Diener. Look how nice everybody keeps their children.

A black wrought-iron fence marked the fourteen-foot-wide Diener homestead, with black-enameled twin gargoyles carved at the front gate. Here George took to climbing and sitting. But, like his rock in the stream, like the trees he would climb in nearby Forest Park, it was more a place to observe without commitment, more a place to see than be seen.

Years later, George would say, The one thing about my growing up in Brooklyn was how ordinary it was. It must have been hard eating chopped meat five nights a week, but when youre in the middle of a Depression and so is everybody else, then you dont know any better. I had a father who worked hard, and, even though I cannot remember him ever taking me in his arms and saying, I love you, son, I guess I was secure in his love. And I had a mother who never seemed to get the mortgage quite clear. Just when she was near the final payment, she would have to renew. She never made any money off the other apartment, because there was always some needy relative turning up, and Mama would move us up and down from one apartment to the other to make room. Sometimes they would bring the dead aunts and uncles to our house and lay them out in the parlor next to my bedroom, but that didnt bother me. This was what was done, this I accepted. I didnt question my parents authority. I took what was dished out to me.