All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Anita Loos Trust for permission to reprint an excerpt from Cast of Thousands by Anita Loos (Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1977).

Copyright 1977 by Anita Loos. Reprinted by permission of Ray Pierre Corsini, agent for The Anita Loos Trust.

Duchin, Peter.

Ghost of a chance : a memoir / Peter Duchin with Charles Michener.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-375-75131-9 (alk. paper)

1. Duchin, Peter. 2. MusiciansUnited StatesBiography.

I. Michener, Charles. II. Title.

Book design by J. K. Lambert, adapted for ebook

1

MAKE SOMEONE HAPPY

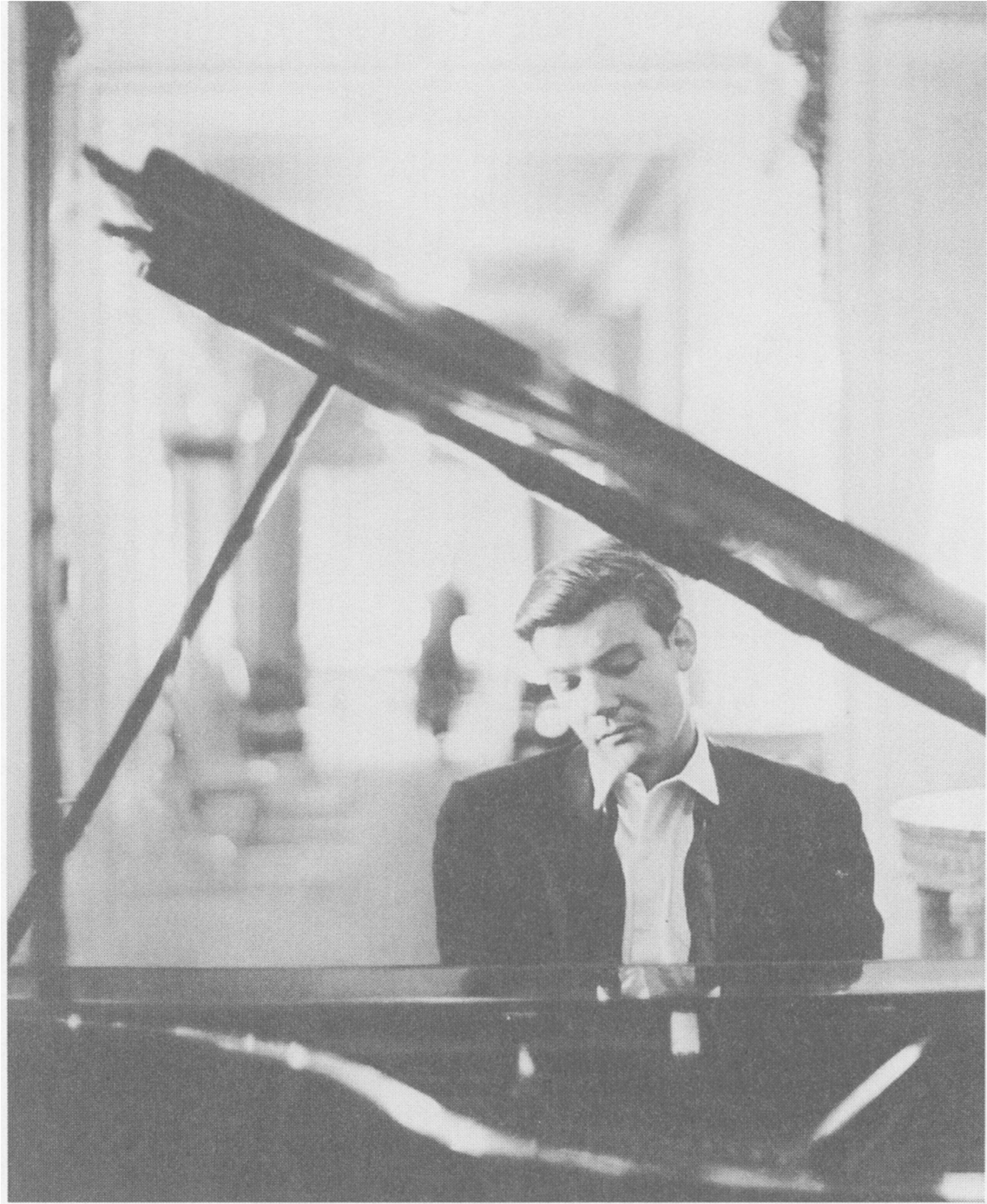

When a young man kills his first stag, our Scottish gardener used to say with great seriousness, the older hunters smear the animals blood on the lads forehead. Its called blooding. I must have been almost ten when I heard that story, but, weirdly, I started thinking about it fifteen years later, as I stood in the bathroom of a suite in the St. Regis Hotel, staring in the mirror at a small shaving cut on my neck. It was the night of September 25, 1962, and the older hunters were all downstairs, dressed in black tie, waiting for me to attend to the stag.

I stuck a piece of toilet paper on the cut, splashed cold water on my face, and tried to fix my tie to hide the red spot on the collar. The guy looking back at me was scared to death. I had just turned twenty-five, and I was about to make my professional debut as a bandleader, not in some out-of-the-way dump where nobody would notice but right at the top: the Maisonette in the St. Regis, one of the classiest supper clubs in New York. The audience was a killer, tooseveral hundred celebrities, newspaper columnists, and people from cafe and old society.

A pair of ivory-backed hairbrushes that had belonged to my fatherthe old-fashioned kind with hard badger bristles that fit togetherwas lying on the edge of the marble sink. I slicked back my hair with them, then pulled up my suspenders, clamped on the cummerbund, put on my dinner jacket. I checked my watch, a gold Omega with a black alligator band. It had also belonged to my father. Dads ghost was all over this event. The Maisonette was exactly the sort of place he had owned in the thirties and forties, when the Eddy Duchin Orchestra was one of the most famous bands in the country.

Out in the sitting room, I poured myself a drink. On the wall above the little bar was a mezzotint of a Scottie dog that looked just like Kilty, the pooch that had belonged to my maternal grandmother, Mammy Oelrichs. Mammy had lived at the St. Regis for years, or at least for as long as Dad had paid her bills. When I was a kid, Id occasionally visit her for tea. Shed draw me into her bosom, which reeked of Chanel, and my blazer would get smeared with her white face powder. I remembered wonderful pastries arriving on a silver tray from room service after wed taken Kilty out for a sedate walk in Central Park.

Tonight there were no tea and cakes, although Csar Balsa, who owned the St. Regis, was throwing a little warm-up downstairsa cocktail party for the press and a few old friends. I finished off the Scotch and checked myself one more time. The blood had dried. Gingerly, I removed the toilet paper.

The first person I ran into at the party was Dorothy Kilgallen from the Journal-American: no chin, pounds of pale makeup, big doll eyes. She whipped out a notebook. How do you feel?

I cant believe this is happening to me, I said, gamely.

She had her quote, for what it was worth, and moved over for the next guy, John McClain, the Hearst columnist. John had been a friend of Dads and one of the hosts, along with Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart, of a legendary party theyd all thrown in L.A. in 1946, when I was nine. I got tears in my eyes, kid, John said. If only Eddy were here.

Next came Popsie Whitaker of The New Yorker, a wonderful heap of a fellow who reminded me of a crumpled newspaper. I mumbled some inanities, then turned toward the tall Dorothy Lamour look-alike who was smiling at me: Chiquita, my stepmother. A couple of years earlier, when I was sweating it out as a glockenspielist in the Army Band in the Canal Zone, Chiq had invited me to Mexico City for a little R and R. One night we went to a restaurant called Uno, Dos, Tres, and after too much to drink I started playing the piano. When the owner heard that the kid fooling around was Eddy Duchins son, hed handed me his card and murmured, Call me when youre back in New York. He was Csar Balsa.

As Chiq was saying how proudat lastshe was of me, all three hundred pounds of Toots Shor glided over. Id known Toots most of my life. Back in the twenties and thirties, he was a bouncer at Leon & Eddies, the speakeasy on West Fifty-second Street. When he wanted to open his own saloon after Prohibition, Dad gave him a blank check. Toots never cashed it. He didnt even tear it up. He called it visual collateral.

Toots was family. Everything at his place was on the house for me and my pals. Toots had made sure I wasnt alone at the screening of The Eddy Duchin Story, the Hollywood tearjerker about my fathers life. Watching Rex Thompson, the brat who played me in knickers, Id wanted to hide under the seat, and when the movie was over Id felt pretty beat up and confused. As we were leaving the screening room, Toots put his big paw on my arm.

Pete, when were you born?

July twenty-eighth, 1937.

What was it in the movie?

Some day in December.

He punched me gently on the shoulder. See what I mean? Its all a load of crap.

Now he punched me again.

The couple right behind Toots were more family, and I kissed each of them in turn. First, Ma, my godmother, Marie Harriman, looking sexy behind her dark glasses. Then her husband, Averell, the former governor of New York and ambassador to Moscow, now a big deal in the Kennedy State Department. Ave wore a dinner jacket that had undoubtedly been made by the little Italian tailor who came twice a year to his house on East Eighty-first Street.

Ma was dragging on a Viceroy in a white plastic cigarette holder. This is the night weve been waiting for, kiddo, she said.

Ave beamed his all-purpose smile. Youll do just fine, Petey.

Ginny Chambers, my other godmother, sailed up. I never lost hope, darling. Though you certainly pushed it. Ginnys whiskey baritone crackled through a wreath of cigarette smoke. Do you believe it, Marie, after all this kids put us through?

1

1