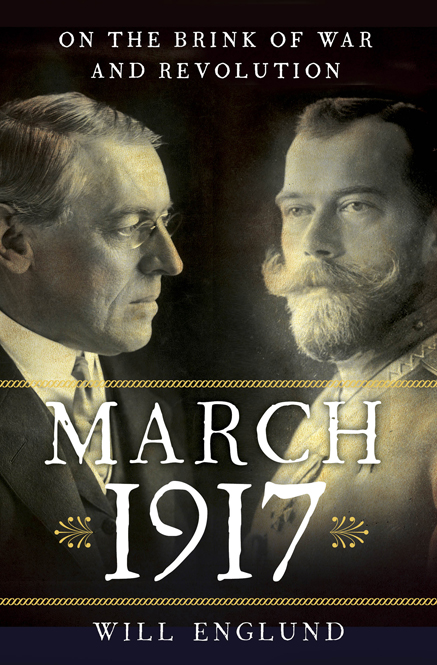

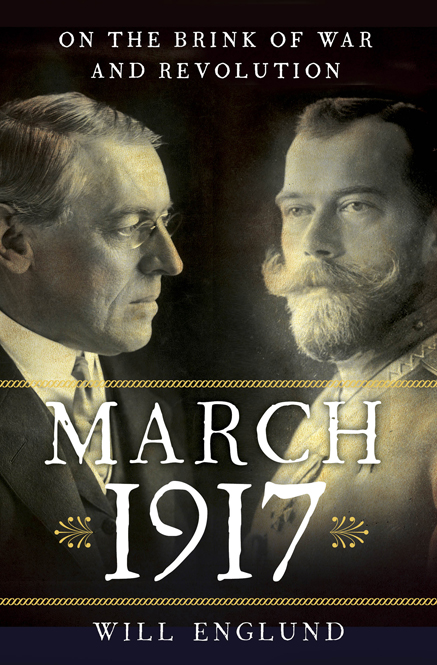

MARCH

1917

On the Brink of War and Revolution

WILL ENGLUND

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York | London

Francis McLaughlin, twenty-one, of the 15th Ward of Philadelphia, registered for the draft on June 8, 1917. He was of medium height and slender build, with brown eyes and dark hair. He had a job making artillery shells at the Baldwin Locomotive Works, near where he was living on Francis Streetwork he had undoubtedly secured through his father, Patrick, an Irish immigrant who had been a blacksmith at Baldwin for decades. The munitions job didnt exempt him from the draft, and by 1918 both he and his older brother James were in uniform, and Francis was on the Western Front.

Their sister Isabella was my grandmother. I dont know much more about James or Francis than that, because while my great-grandfather Patrick didnt object to his two sons joining a war effort that allied their country with the detested English, he would not stand for the marriage his daughter made with a Swedish Protestant. She was cut out of the family. The wounds of the Irish were fresh and their ferocity was deep a century ago.

A German gas attack seared Franciss lungs, and I always heard growing up that he had come back to Philadelphia to die. Yet a census taker in 1930 found him alive, if not well, living with several of his siblings, unmarried, working not in a factory job but as a clerk in the Philadelphia tax collectors office. In the column marked veteran were the letters ww, for World War. I dont know what became of him after that.

So here let me acknowledge Francis McLaughlin and James and the two million other men and women, so many nearly forgotten now, who did their duty as they saw it and propelled the United States into the forefront of the century to follow, sometimes at great cost to themselves. The lives of Americans today were shaped to no small degree by what they accomplished.

THE IDEA FOR this book evolved considerably over quite a few years, in fits and startsmore of the former than the latter. I am grateful to the editors of the Baltimore Sun for sending my wife Kathy and me to Moscow as correspondents, not once but twice, and to the editors of the Washington Post for sending us yet again. At National Journal, editors Charlie Green and Steve Gettinger enabled me to learn something about the ways of Washington and about presidential history as I covered the White House for two and a half formative years, at the end of George W. Bushs last term and the beginning of Barack Obamas first.

Yelena Ilingina helped me understand a Russian way of thinking, in her sharp-witted and indefatigable way. When we were working together and she saw me holding back from a foreigners uncertainty, she pushed forward. She despaired of my floundering in the Russians beautiful language, but she never gave up on me. Together we traveled far and wide. The late Dmitri Likhachev told me what it was like growing up in St. Petersburg and then surviving in Leningrad. Natasha Abbakumova encouraged me no end on this project and was a sure source of Russian perspective. Volodya Alexandrov helped enormously with logistics. A steady guide to Russian reality was the eccentric and marvelous Andrei Mironov, who until he was killed in the fighting in Ukraine in 2014 was the indispensable friend. One of the Soviet Unions last political prisoners, he had a keen sense of history and of farce. He was honest and ever unafraid.

SO MUCH IS available online now that we hardly remark on it anymore, but its worth tipping the hat to a few sites in particular. Chronicling America, a joint project of the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities, has digitized many dozens of newspaper archives, from 1836 to 1922, in searchable form. Eleven million pages are available. HathiTrust and Internet Archive have posted millions of books now in the public domain, also searchable. Of particular use to me as well were the diary of Edward House, posted online by the Yale University Library, and the Josephus Daniels diary, online courtesy of the University of North Carolina.

Still, live librarians are hard to beat. I found welcome assistance at Princeton University, at New Yorks Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, at the West Palm Beach Public Library, and in the manuscript room of the Library of Congressan institution that always makes me feel a little more patriotic every time I visit. The staff at the National Archives II in College Park, Maryland, guided me cheerfully through State Department records even though I had failed to give them adequate notice of my visit. I want to thank especially Wendy Chmielewski of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Elizabeth Shortt of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library in Staunton, Virginia, and Vince Fitzpatrick, who made it possible for me to consult the original copy of H. L. Menckens Berlin diary at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore.

The archivists of the Montana Historical Society, in Helena, were unflagging and creative in their assistance. Anita Huslin, a former Post reporter, and Larry Abramson, onetime NPR correspondent who is now dean of the journalism school at the University of Montana, graciously put me up in their mountainside home when I visited Missoula, Jeannette Rankins hometown. I had a fruitful conversation with Betsy Mulligan-Dague, executive director of the Jeannette Rankin Peace Center in Missoula, and an eye-opening visit to the Butte Labor History Center. James Lopach and Jean Luckowski kindly shared with me their thoughts about Rankins motivations.

EARLY ON, ANDREW Stuart patiently taught me something about the book trade. Steve Luxenberg offered research advice, Robert Ruby reminded me to focus on the main thing, David Brown asked flatteringly detailed questions, and Scott Shane gave me the benefit of his authorial experience. Stephen Hunter gave me a tutorial on vintage guns. Brian Thomas, of Collegeville, Pennsylvania, was generous with his time. Dianne Donovan was always willing to lend me an ear and on more than one occasion gently talked me out of pursuing an unworkable approach. She knows books, and she knows writing, and she was constant in her support. Linda Cullen, Colleen Jordan, Brian Murphy, Michael Kimball, and Anna Fifield reassured me when I needed it. My agent, Gail Ross, is the sort of no-nonsense person every writer needs. John Glusman, my editor at W. W. Norton, grasped the idea of the book instantly, and kept mesometimes sternly, but always smartlyon course. His assistants, Alexa Pugh and Lydia Brents, dealt with my many first-timer questions with patience and aplomb. The copyediting, by Fred Wiemer, was exacting, precise, and impressive, and saved me from more embarrassing mistakes than I care to admit.

Molly Englund, my daughter, helped me more than she knows with her interest, insights, and encouragement. Her sister Kate has an especially keen eye for the visual, which is no surprise for someone who works at Getty Images. Kates husband, the photographer David Rothenberg, offered trenchant advice as well, and he sparked my interest in early twentieth-century Berlin, where his family lived. (At least one of his forebears also fought in the war, on the German side.)

Who helped the most? Well of course it was Kathy Lally, my wife and partner in journalism for decades. She knew when I was ready to write and pushed me to do it; she kept me out of the deep weeds of research (railroad statistics from 1916 come to mind); she endured my thoughtful (I hope) silences at the dinner table. I told her that if she caught me wearing a stiff detachable collar, shed know Id dived in too far. That, fortunately, never happened. She read every word I wrote and made astonishingly clear suggestions for improving the manuscript. I owe her.

Next page