Contents

Boy About Town

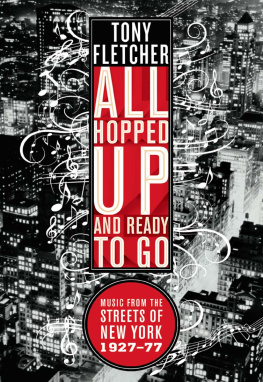

Tony Fletcher

About the Book

I was no longer fitting in at school. I was unsure of my friends, and they were increasingly unsure of me. I wanted to be a rock star a punk rock star, if need be. But while all around, voices were starting to break, acne beginning to appear, facial hair sprouting, I remained all flabby flesh and innate scruff, with a high-pitched whine and not a muscle to my name. I could come top of the class, I could converse with the older teens on the football terraces and with adults in record stores. Yet I was the runt of the class and rarely allowed to forget it. I had no father at home to help me out, and could hardly talk to my mum. So I took solace in The Jam.

As a boy, Tony Fletcher frequently felt out of place. Yet somehow he secured a ringside seat at one of the most creative periods in British cultural history.

Boy About Town tells the story of the bestselling authors formative years in the pre- and post-punk music scenes of London, counting down, from fifty to number one, attendance at seminal gigs and encounters with musical heroes; schoolboy projects that became national success stories; the style culture of punks, mods and skinheads, and the tribal violence that enveloped them; life as a latchkey kid in a single-parent household; weekends on the football terraces in a quest for street credibility; and the teenage-boys unending obsession with losing his virginity.

Featuring a vibrant cast of supporting characters (from school friends to rock stars), and built up from notebooks, diaries, interviews, letters and issues of his now legendary fanzine Jamming!, Boy About Town is an evocative, bittersweet, amusing and wholly original account of growing up and coming of age in the glory days of the 1970s.

For Ruth,

For everything

Number 50: COULD IT BE FOREVER

DAVID WAS MY first love. Not David Bowie, though it was Bowies single Starman that brought my eight-year-old self, my eleven-year-old brother and our thirty-something mum to this place in time: Counterpoint Records in Crystal Palace, a Saturday in summer, 1972. My brother Nic had watched Top of the Pops two nights earlier and been transfixed by the sight of Bowie, sporting orange hair, an amazing Technicolor jumpsuit and a blue guitar, throwing his arms around a guitarist whose gold lam two-piece suit matched the colour of his own considerable mane. The visual impact, and perhaps even the music, had sent him running to our mum, begging her to buy him a copy. It was the first time hed ever asked for a record of his own.

Id already pestered our parents into buying me a couple of singles over the years: Back Home by the 1970 England World Cup Squad because what self-respecting six-year-old football fan could possibly go without? and, much to my dads dismay, Somethings Burning by Kenny Rogers, which Id fallen for on one of the few occasions Id been allowed to watch Top of The Pops. Dad, the head of music for the Inner London Education Authority, had always frowned on pop. Wed been brought up learning the cello (me), violin (Nic), piano (both), and taught to read music almost as soon as we had learned the alphabet. My brother spent his Saturdays in Pimlico, at the music-school-within-a-school that Dad had recently founded in the comprehensive there; I was expected to follow imminently.

Still, when hed left home a few months earlier, the culmination of incompatible parental tensions evident even to a small kid like me, Dad also left behind his collection of late-sixties Beatles albums that appeared to provide the exception to his musical rule. Id enjoyed isolating them from the symphonies and operas that otherwise dominated the record cabinet, singing along to those songs which made sense to me: Maxwells Silver Hammer, Piggies, When Im Sixty-Four and Your Mother Should Know. The pop bug was something Id surely been born with. It was just that, until now, Id been prevented from tending to it.

But with Dad having moved over the river, the mood around the house suddenly changed. It wasnt all for the good: Mum told us that he wasnt paying his share, so she worked a couple of evenings a week at the Youth Club at Norwood Girls School, after already working there all day, teaching English to kids who didnt speak it the way they did on the BBC. And Nic and I had to spend alternate weekends at Dads posh new flat in Pimlico, the very notion of which brought on migraines for me if some sense of continued bonding for my older brother. Still, freed from Dad commandeering the living room every other night to rehearse the teenage male prodigy violinists he was grooming for his London Schools Symphony Orchestra, we found we could suddenly start behaving like kids were meant to behave and that Mum could act like a mum was meant to act around kids. Allowing us to watch Top of the Pops and watching it with us was a major first step. So was taking us to the record store. Mum even got her own single at Counterpoint that day: Walkin In The Rain (With The One I Love) by Love Unlimited, which came complete with watery sound effects, a high-pitched female chorus and the sound of a man talking to his woman on the telephone in the deepest voice youd ever heard. Her choice, I figured, was influenced by the teenage girls at Norwood: it wasnt exactly like the music she sang with her group, the Bach Society.

Now, as we stood there by the record counter, she invited me to choose a single as well. But, my interest in pop music having previously been denied, I had no idea what to get. I stared at the racks of 45s, most of which were in plain paper sleeves. They meant nothing to me. I studied the list of the current Top Thirty, laid out in moveable white letters on a black board near the counter. I didnt recognize any of their names. So I did what seemed natural for an eight-year-old. I asked my big brother for advice.

He examined the ranks, as cagily as I had. Just because hed watched Top of the Pops the other night didnt make him an authority. All Nic knew was that by cuddling with his guitarist while singing about a starman who thinks hell blow our minds, David Bowie had made history and that all the kids in his class wanted to be, or buy, a part of it. Finally, he fingered through the rack of half-price singles records that had recently fallen off the charts and pulled out the only one that came with a picture sleeve. It was called Could It Be Forever.

You should get David Cassidy, he said, with evident relief, showing me a round feminine face that filled the whole of the cover in colour. All the girls love him.

I was not a girl, but that wasnt the point. He recommended David Cassidy because he thought it was the limit of my expectations. As if to prove him right, I took him up on it. The next I knew, singles in hand, we were walking back to wherever Mum had parked the Hillman Imp and heading down Gypsy Hill towards home a modern Wates estate of narrow terraced three-story houses called Little Bornes, sandwiched in between the expensive homes of West Dulwichs Alleyn Park and Sydenhams massive Kingswood Estate. Low garden fences separated us from our posh neighbours to the front, a twelve-foot fence from the poorer estate to the back. England could be funny like that.

When I finally got to hear it in full, at home, Could It Be Forever was sugary sweet almost to the point of sickliness, nothing like the alien sounds of David Bowies Starman. But once I convinced myself that I liked it anyway, then David Cassidys feminine face revealed itself as deeply handsome, a fragile symbol of male tenderness. I tried to assure myself that his shoulder-length hair mirrored my own bowl-like cut, even though his was dark and mine was blond. If David Cassidy could look so girly and yet be so popular, then one day, I figured, so could I. And with that, the idea of being a pop star suddenly seemed as worthy a goal in life as any especially for a kid like me, who was precocious beyond all acceptable limits and who craved the attention that came with it, a kid who thought nothing of heading out alone on his bicycle all over the surrounding neighbourhoods and yet who clung too close to his mothers apron for eithers benefit, who worshipped footballers and wished he could be one himself and yet who was overweight and emotionally unstable, as evidenced in easily provoked and alarmingly frequent crying fits. I played the record again and I was convinced. Yes, David, I swore of my first love, it

Next page