This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To my Father

and

in memory of my Mother

who nurtured my love of History

and by encouraging regular church-going

made me permanentiy interested

in how those buildings got there and what they were for.

In memory also of

Nico Colchester

my cousin and beloved friend,

a man of rare quality and manifold talents

whose life was tragically cut short

in 1996 at the age of only forty-nine

with whom I often discussed this book

in remote places far from libraries

in Devon and the Cevennes.

History, I think, is probably a bit like a pebbly beach, a complicated mass, secretively three-dimensional. It's very hard to chart what lies up against what, and why, and how deep. What does tend to get charted is what looks manageable, most recognisable (and usually linear) like the wriggly row of flotsam and jetsam, and stubborn tar deposits.

Richard Wentworth

Enormous simplification were possibly necessary to carry a deeper truth than lay on the surface of a mass of unsorted detail. That was, after all what happened when history was written: many, if not most, of the true facts discarded.

Anthony Powell

Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure.

Jane Austen

1 The Mediterranean world in late antiquity 20

2 To illustrate the activities of Martin, Emilian and

Samson, from the fourth to the sixth centuries 41

3 To illustrate the activities of Ulfila during the fourth

century 69

4 To illustrate the activities of Ninian and Patrick in the fifth

century 78

5 Gaul and Spain in the age of Amandus and Fructuosus,

seventh century 137

6 The British Isles in the age of Wilfrid and Bede c. 700 164

7 The Frankish drive to the east in the eighth century 196

8 The world of Cyril and Methodius in the ninth century 330

9 Christianity in the Viking world, c. 1000 376 10 Eastern Europe and the Baltic, twelfth to fourteenth

centuries 420

Between pages 146 and 147

1. Reconstruction drawing of King Edwin's palace at Yeavering

ad 627 by Peter Dunn ( English Heritage Photographic Library)

2. Ivory plaque showing Jesus raising the son of the widow of Nain from the dead, c. 970 ( British Museum, London)

3. Constantine I ( Staatliche Miinzsammlung, Munich)

4. Zeno of Verona ( Foto-Agenzia Brocchieri, Milan)

5. and 6. Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville ( Photographie T. Deslande, Musees Departmentaux de la Seine-Maritime; Rouen)

7. Inishmurray ( Office of Public Works, Ireland)

8. King Ethelbert's lawcode ( The Dean and Chapter, Canterbury)

9. Queen Theodelinda's comb ( Museo del Duomo, Monza)

10. Sutton Hoo spoons ( British Museum, London)

11. Gravestone of Desideratus ( Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn)

12. Gravestone of Rignetrudis ( Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn)

13. and 14. Gravestones from Niederdollendorf ( Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn)

15. Sao Fructuoso de Montelios ( Roger Collins, Edinburgh)

16. The church at Hordain ( Service Archeologique de Douai)

Between pages 338 and 339

17. St. Cuthbert's pectoral cross ( The Dean and Chapter, Durham)

18. Stone from Papil ( National Museums of Scotland)

19. and 20. Seventh-century brooch from Wittislingen ( Prahistorische Staatssammlung, Museum fur Vor- und Friigeschichte, Munich)

21. Ardagh chalice ( National Museum of Ireland, Dublin)

22. Tassilo chalice ( Stift Kremsmunster and Hofstetter, Ried)

23. Wiirzburg library catalogue ( Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Laud Misc. 126, fol. 260r)

24. Gospel book made for Queen Theodelinda ( Museo del Duomo, Monza)

25. The Lindau Gospels ( The Pierpont Morgan Library', New York, M.l, BC)

26. Enger reliquary ( Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin)

27. Front panel of the Franks casket ( British Museum, London)

28. Glagolitic script ( Foto Biblioteea Vaticana, MS. Vat. Slavo 3)

29. The horseman of Madara ( UNESCO)

30. Memorial stone at Jelling ( Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen)

31. and 32. Cross at Middleton {Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, photograph by T. Middlemass)

33. Runestone at Froso ( Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, Stockholm, photographed by Sven Jansson)

34. Idol of the slave god Svantovit ( Museum Archeologiczne w Krakowie, Cracow)

35. Sainte-Foi de Conques ( Tresor-Musee de VAbbatiale de Ste-Foi de Conques and Sud-Image, Labrede)

36. The sundial at Kirkdale ( Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, photographed by T. Middlemass)

PREFACE

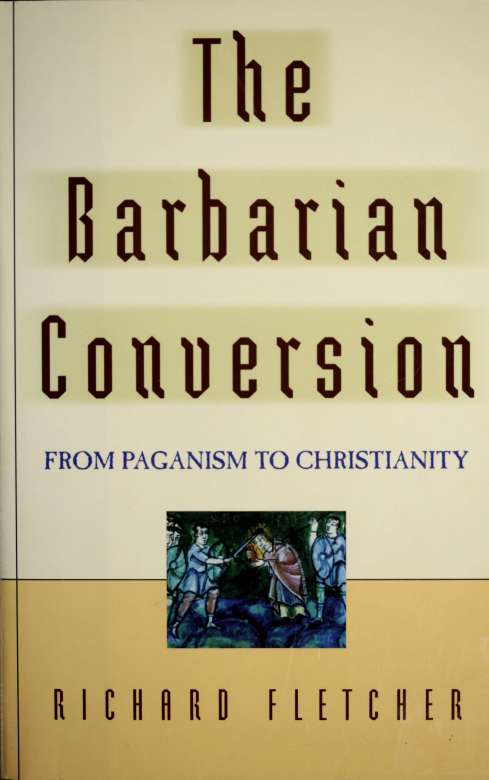

This book is an investigation of the process by which large parts of Europe accepted the Christian faith between the fourth and the fourteenth centuries and of some of the cultural consequences that flowed therefrom. It is therefore unfashionably ambitious in its scope. Professional historians today are expected to know more and more about less and less, and to communicate their findings to other professional historians in those weird gatherings known as academic conferences. In consequence fewer and fewer people are going to listen to what they have to say. It is a wholly deplorable state of affairs when specialists in any discipline talk only to each other, and accordingly I have sought to write a book which will communicate some of the fruits of research in a manner which will make them accessible to all. Whether or not I have succeeded in this aim will be for others to judge. The last attempt at such a survey by an English author was a work called The Conversion of Europe by the Reverend C. H. Robinson, published in 1917. Much has happened in the discipline of medieval history in the eighty years since Canon Robinson's book was published. It is timely to essay a new synthesis.

Very early on in my reflections on this topic I became convinced that it would be imprudent to attempt to explain this process of the acceptance of Christianity. Efforts to do so tend to be superficial and glib. My book proceeds by way of suggestion rather than explicit argument; my preferred method is to dispose the raw building blocks of evidence in such a manner as to move suggestions forward. Implicit argument may, I hope, be detected, to use an architectural analogy, in the disposition of mass and shape. The building is rambling, but I hope it coheres.

There are a few practical points of which the reader needs to be aware. The scope of the book is confined for the most part to western, Latin or Roman Christendom. The history of eastern, Greek or Orthodox Christendom is not my concern, let alone the history of those exotic Christian communities, Ethiopic, Indian and Nestorian, which lay beyond the eastern Mediterranean hinterland. Orthodox