T. S. ELIOT, Little Gidding

T HIS IS NOT the book I intended to write.

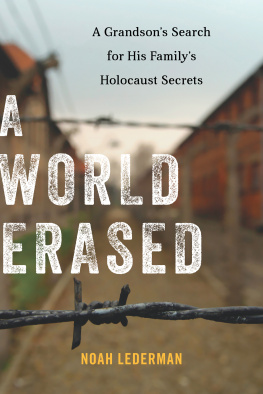

When I left the White House as a speechwriter late in Barack Obamas first term, I wanted to write a book about my moms parents, Bubbie and Zayde, and my dads parents, Grandma and Pa.

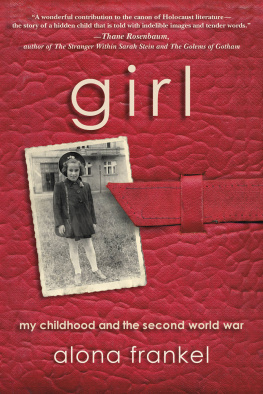

Bubbie and Zayde were Holocaust survivors, and Pa was a Northwestern student peace activist before serving as a platoon leader in the South Pacific. Id been inspired by their stories growing up, and I thought others might be, too.

I also thought their stories were important to tell, particularly as fewer members of their generation are alive to share them themselves. Over dinner a few years ago, a German consular official told me it was getting harder to teach young people about the Holocaust because the most compelling instructorssurvivorsare all passing away.

A 2018 poll revealed the danger of letting that generations stories die with them: two-thirds of millennials in the United States could not identify what Auschwitz was, and 22 percent said they hadnt heard of the Holocaust or werent sure if theyd heard of it. So I started writing this book as a way of keeping that history alive.

I also had another, much more intimate story to tellabout the ways the trauma of the Holocaust has reverberated through the generations of my family. At the time, however, I could not tell that story because I was still living it. And for many years, I wasnt readypsychologically or emotionallyto tell it. Now, I am.

This book, then, is not only about the Holocaust, not only about World War II. Its about the lasting scars of that cataclysm. Not only about the past, but about how that past has stayed with us. Not only about the trauma someone, somewhere in our family may have experienced, but about the ways that trauma can continue to play itself out, from one generation to the next. Part I tells the story of my grandparents experiences during the Holocaust, and parts II and III explore the ways their trauma inflicted pain in my mothers life and, later, my own.

Of course, the traumas that are handed down to us can take different forms. Some of us may be grappling with the cruelty of mental illness or invisible war wounds. Others may be battling the legacy of alcoholism, addiction, abuse, gun violence, racism, or some other scourge.

And yet while the nature of our families traumas may vary, each of us has in a sense the same choice to make. We can turn away from what weve inheritedin some cases an understandable, perhaps even wise decision. Or we can confront it, in the hopes of conquering that traumaor at least moving on. That is what Ive tried to do, and this book is, in part, about how Ive tried to do it.

Adam P. Frankel

New York City, 2019

F ORGIVE HER, MY grandfather told me.

It was just the two of us, sitting across from each other in a booth at Athenian Diner III, a 1950sstyle Greek diner on the Boston Post Road; his favorite lunch spot, where hed always take me on my visits to Connecticut.

The woman he was asking me, pleading with me, to forgive was his daughtermy mother. Zayde didnt know what she had done. My mother hadnt told him, and I wouldnt say. I couldnt bring myself to tell him.

But he was uncannily observant, and sensed shed done something to hurt me, committed some injury I was unable to move beyond.

None of his children were so keenly aware. None, such astute readers of people and situations. Not my uncle. Not my two aunts. They didnt ask why there had been a rupture, instead scolding me for what they saw as my inexplicably cruel treatment of my mother.

Sometimes, I felt like I could hardly blame them. Mom herself not only tolerated the scorn they showed me, the withering judgment, she often seemed to encourage it, portraying herself as an innocent victim of her sons slights, even as she knew they didnt have all the facts.

I looked at my grandfather, the light beating against him, his mushroom omelet half eaten on his plate, the intensity of his stare making his words seem less a request than a command.

I said nothing, and the silence stretched on. One second. Two seconds. Three seconds.

What could I possibly say to this man, who had nearly lost his entire family in the Holocaust, who had been separated from his mother in a concentration camp and never seen her again?

I also wondered: Was the trauma that he and Bubbie endured all those years ago at the root of everything? Had it in some way contributed to the troubles that had plagued my mother all her life? Somehow created the circumstances that were wreaking such havoc in my life?

Whatever she did, he repeated, forgive her.

If we have our own why of life, we shall get along with almost any how.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE, Twilight of the Idols

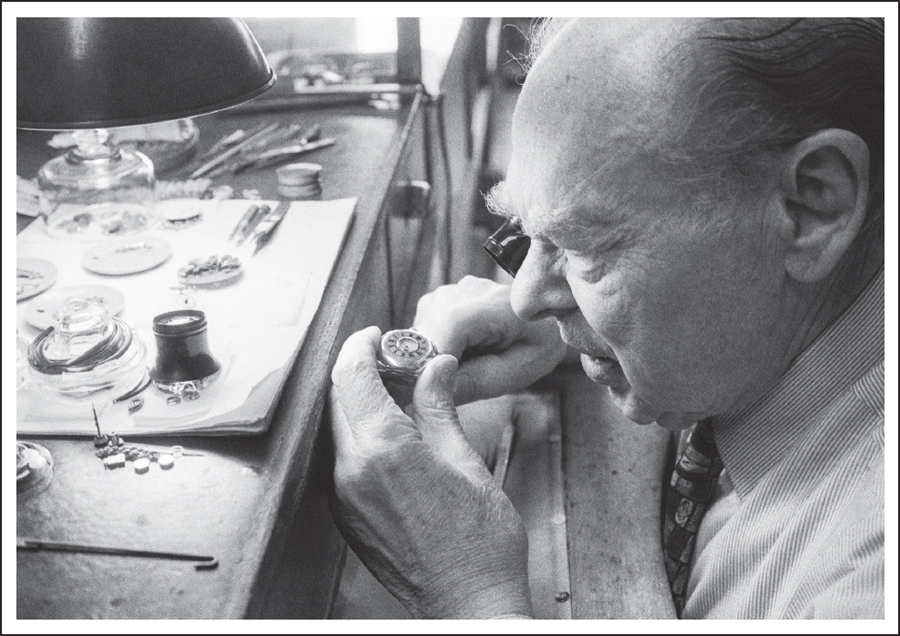

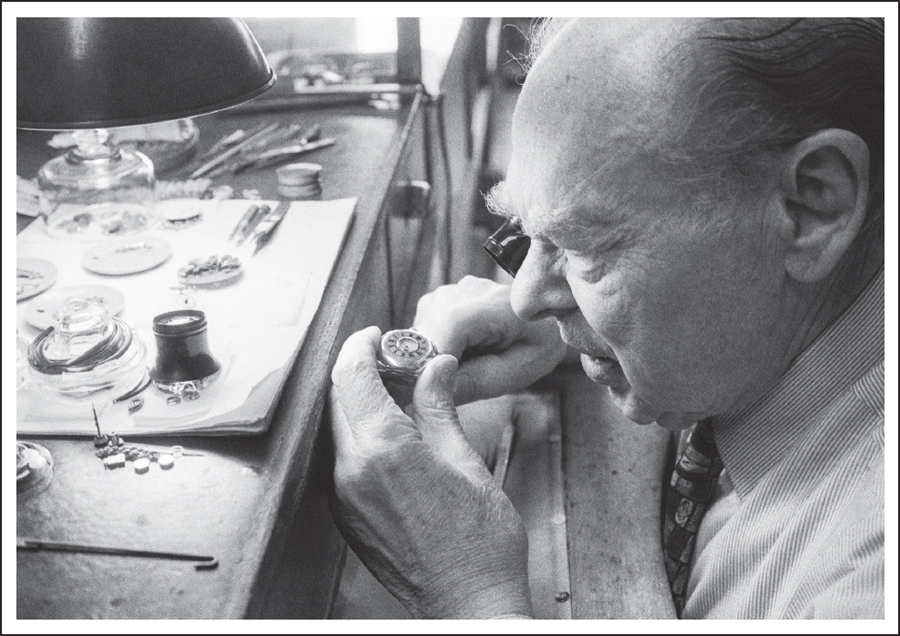

Zayde repairing a watch at his bench.

2001 David Ottenstein

I N THE WINTER of 2012, I received a call from my mother, saying my grandfather needed surgery.

One year earlier, he had fallen on an uneven sidewalk in New Haven. Hed taken quite a spill, and some passersby had called an ambulance. The paramedics insisted on taking my grandfather to the hospital, but he protested. Im fine, Zayde said, blood dripping from his forehead. Only after he signed a waiver did they finally let him go.

When news of the fall spread in our family, everyone urged him to see a doctor. Get checked out, we said. Make sure nothing is broken. But Abraham Perecman is a stubborn man, and there was nothing we could do.

Not a word was spoken about the incident, not even a whisper of complaint from the man himself, until this call from my mother one year later. Apparently, when my grandfather fell, he had fractured one of the uppermost vertebrae in the neck, the C2. And the break had begun healing awkwardly, putting pressure on his nerves.

Family began to notice him shuffling his feet. Less visible, but more worrisome to Zayde, was the loss of feeling in his fingers. The possibility of being unable to repair watches was unthinkable.

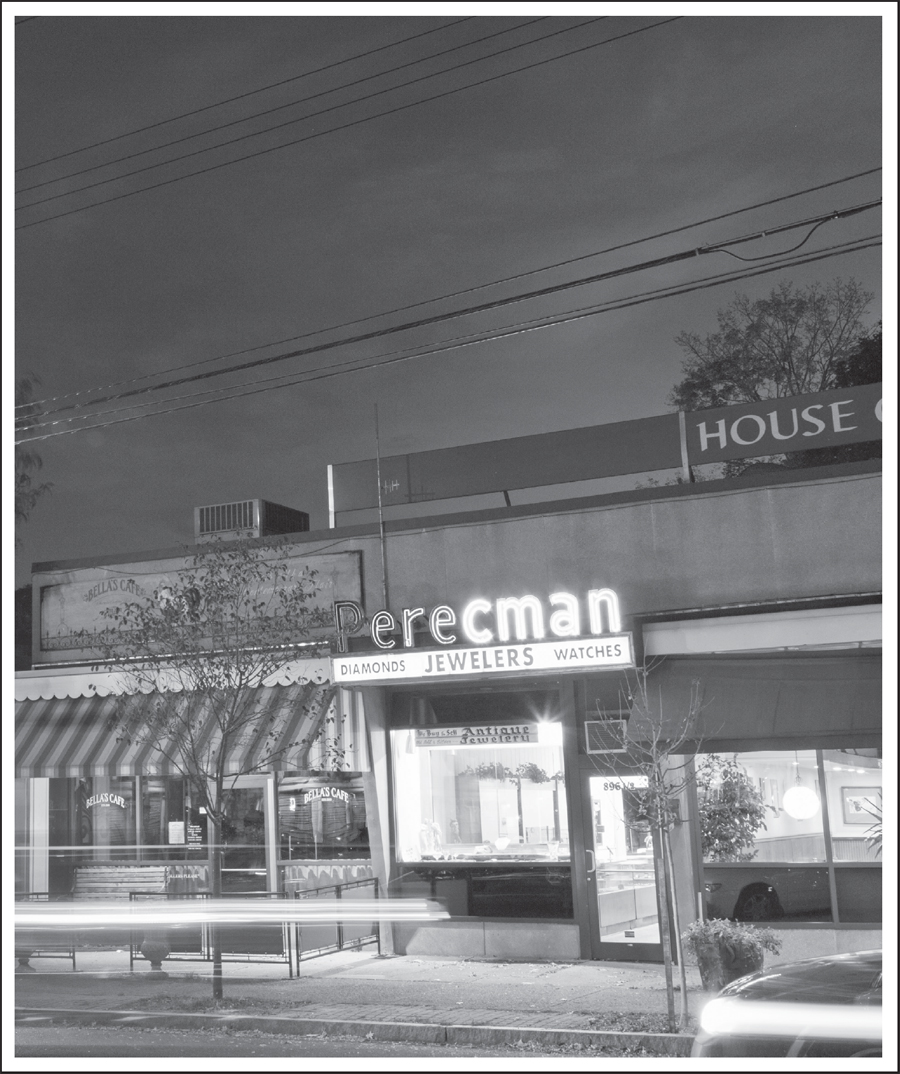

Watches are the mans life, and repairing them, his livelihood. His little shop, Perecman Jewelers, occupies 896 / Whalley Avenue, beneath the shadow of West Rock, a rusty peak overlooking the city. From the outside, The Store, as everyone in the family calls it, looks every one of its nearly sixty years, declaring the name of its proprietor in fat neon tubes. The P stopped working years ago; the E-R-E emit only a dull glow.

We buy and sell gold and silver, reads a hand-drawn sign in the window, a pull for the occasional walk-in. The avenues namesake, seventeenth-century English judge Edward Whalley, was a signatory to Charles Is death warrant before fleeing to the New World, the firstbut not lastrefugee to settle in the neighborhood.

The entire store is a single aisle, ten paces long with a dropped ceiling overhead, brown linoleum tiles underfoot, and a musty smell hanging in the air. On the left are waist-high glass showcases, their tops bare except for a twirling hand-held mirror, a cardboard coin folder for a childrens leukemia charity, and a rotating plastic dispenser of Twist-O-Flex watchbands.