Table of Contents

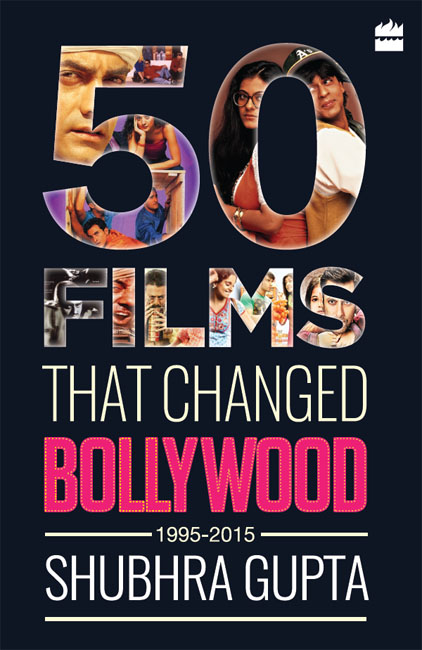

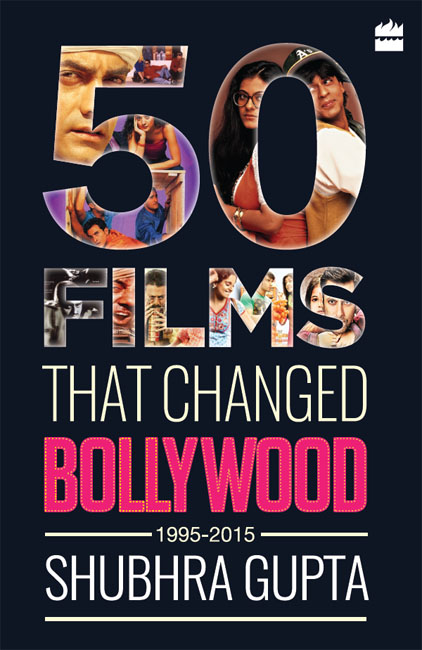

50 FILMS THAT CHANGED

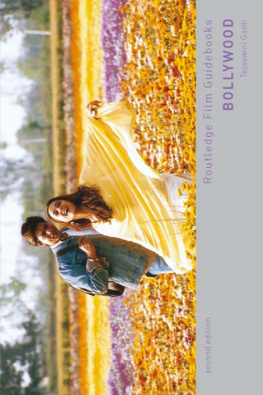

BOLLYWOOD, 19952015

Shubhra Gupta

To my mother. And her mother.

The two who made me, me.

CONTENTS

When are you going to write a book?

For the longest time I would respond with, When I have something to say, and hope that it didnt sound too feeble. Now I can safely stop dodging this frequently asked question.

The thing is that in the life of a constantly plugged in, card-carrying film critic, there are no full stops. Only commas, semicolons and dashes, and sometimes screeching exclamation marks, created by the films one has to see. Films keep flooding into theatres every week. At least one; most often two or three, or even more. It is a barrage. And then those weeks become months and years. If my reviews say what I have to say about the films, what is left over?

By now, enough. The years that I have spent at the movies have added up to become more than the sum of their parts. The sense of history and context and understanding of how films are so much more than a series of visuals connected by a plot, how they are made and put out there, how they are received, where they come from and where they go is sizeable enough to trace the journey of how Bollywood grew in the weeks, months, years that one was watching.

Bollywoods journey has been mine too.

People often ask me how many films I have seen over the years, helpfully throwing out figures: hundreds, thousands, or more? And I tell them I stopped counting long back. Because watching and learning and growing has been a work in progress for me. Cinema, of all kinds, teaches me to see, and share.

So here it is, finally. The Book. Because I do have something more to say than what Ive already said, and continue to say, in my weekly reviews and fortnightly columns.

* * *

I began writing on cinema in the early 1990s. It started as a lark, filling in for on-leave film reviewers in the papers I then worked with, or, once, even moonlighting for a rival Sunday paper (the bit of money I got paid was incidental but a welcome addition to my meagre journalist salary!). It was just for a few weeks, but it was enough to make me realize that I enjoyed it more than anything else I was doing at the time. Which was reporting, editing, making pages, just the regular stuff that journalists did while, of course, changing the world.

The film review column you see in The Indian Express today began in the early 1990s, and it has had a continuous run in the paper since then, with practically no breaks (barring the odd week or two). When I began, I also used to write a regular column on television, and it was fascinating to see how disparate and yet how connected these two mediums were, because when it came to grabbing eyeballs, the great glue was cinema: there was nothing more sticky than the Sunday evening movie or Chitrahaar, and all the hundreds of film-based programmes that rolled out when Doordarshan stopped being the only act in town, and satellite channels began sprouting at a breathless pace.

In the last two decades and more, India has changed beyond recognition. Along with everything else, it is evident in our mediascape with its multiplicity of platforms, which we create and consume 24/7, so different from the time when we had one grainy official news channel, a stuffy sarkari radio station and a handful of newspapers minus shiny supplements. That was an India in which Wrigleys chewing gum and Wrangler jeans, and other foreign products, were prized possessions, and we had to hide a few extra greenbacks in our socks on the rare visit abroad because the RBI had strict rules for how much forex we could take with us. We now live in a country whose metros are buried under high-end brands and glitzy malls, Japanese and American SUVs (sports utility vehicles) rule the roads, and foreign travel is a routine, mundane, to-be-taken-for-granted thing.

As a film critic who has stayed the course these twenty years and more, Ive been a privileged bystander-cum-participant, experiencing the transition first-hand. From mouldering single-screen theatres with rickety seats and unbearably stinky loos to swanky multiplexes with five-star toilets, flatbed seating and valet service. From distributors who ruled their turf with velvet gloves and iron hands to faceless number crunchers. From hands-on exhibitors who would welcome you themselves and order samosas and chai and greasy popcorn to nameless drones controlling things from faraway offices. From producers known for their immense hospitality with their Diwali parties and holi milans to cut-and-dry corporate houses owing allegiance to their Hollywood bosses. From funding which came from private hundis at exorbitant interest rates and dodgy sources to the possibility of clean bank loans and collaterals. From films which used to be written as they went along to bound scripts and professionally managed sets. From reviews written on Saturdays which appeared on Sundays to tweeted insta views to films released on Netflix and iTunes I could go on and on.

In 1991 came liberalization, and India became a different country. In 1995 came Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ), and Hindi cinema became Bollywood.

There have been as many definitions of what Hindi cinema and Bollywood was and is, and the differences between the two, as there have been opinions on the origins of the term Bollywood, voiced and argued over by eminent scholars and social scientists and other worthies. For me, the changeover came with DDLJ. It was like a distinct click and settling, a Before and After. The slow transition had begun in the early 1990s, but with this film there was a sense of clear departure; the sense of an ending and a beginning.

Shah Rukh Khan aka SRK, the films male star, personified that difference. He was a middle-class Dilli boy who attended a well-known school and a middling college and a postgraduate media course. He romanced a girl next door and married her. He arrived in Bombay with a wife and some friends, and an ambition that was a fire in his eyes. He had done theatre with Barry John and acted in a Doordarshan serial, from which he began gaining popularity, and now he was aiming for the movies.

As a young reporter, I was once assigned to cover a play he was in. I reached Kamani Auditorium, where the group was rehearsing, and there he was, this TV guy on stage. He looked unremarkable at first glance, and then you paused. I remember thinking he looked slighter than he did on TV, but he had that extra something: he caught the light. He was, even back then, a little more visible.

His journey has been documented a million times over, but twenty-five years on, and even after those many iterations, it is as amazing: it reflected the new Indian who had broken free from the socialist era and the licence raj, and the privileged club ruled by unseen hands where you gained entry only because of your birth or by your access to the powerful. SRK made it big on his own steam. Unlike the other two Khans, he is usually (and erroneously) compared with, he did not have old family connections in Bombay. He began with a barely seen Mani Kaul film, and made his first big Bollywood splash astride a motorbike on Marine Drive, singing a song: many people before and after had done the same, but SRK took it and ran with it. And he hasnt stopped still.

He was one of us, and he is on top. That makes him the ultimate outlier.