To the films, filmmakers and film viewers of the 90sd

Contents

There is really only one possibility failure.

Robert Warshow, The Gangster as Tragic Hero

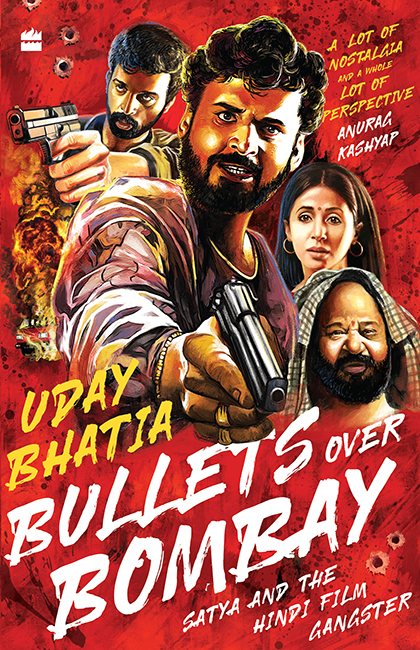

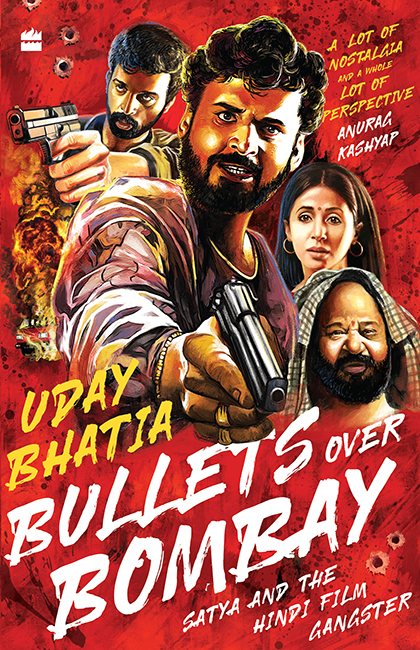

I n 1964, while promoting his film Bande part, Jean-Luc Godard repurposed a line from American cinema pioneer D.W. Griffith. What do filmgoers want? A girl and a gun. Like the French directors other famous aphorism cinema is truth 24 times per second it was glib, but it stuck. Guns and girls, danger and beauty there, apparently, for the gratification of the boys on screen and in the audience. This adage certainly applies to Indian commercial cinema, whose practitioners know the value of a thrill introduced for thrills sake except here its a girl and a gun and a song and a mother and a god.

Lets look at one Indian film in particular. Theres a girl, not the Godard kind, but nave and warm. Theres a gun in the hands of her lover. The film is about him, but it all started with a similar girl in a book. And it was named for a girl. To this, we add one more thing: Mumbai.

A girl, a gun, a boy and a city. Satya.

August 1997. Independent India turns 50. Sachin Tendulkar scores back-to-back Test centuries against Sri Lanka. Word is getting around that Kajol is the killer in Gupt. Everyones talking about The God of Small Things, which will go on to win Arundhati Roy the Booker Prize. The market is holding itself together even as Asia collapses. Two months after 59 people die in a fire during a screening of Border in Delhis Uphaar cinema, moviegoers continue to frequent theatres. And Ram Gopal Varma, with goodwill left over from Rangeela but knowing hes messed up Daud, sets out to make a film on the Mumbai underworld.

Eleven months later, Satya opens to critical acclaim and modest business. Did anyone then guess it would be relevant two decades later? All anyone could talk about in 1998 was Kuch Kuch Hota Hai. Karan Johars film, a college romance which catches up with its central characters later in life, unfolds in a fantasy India where students wear designer clothes and are totally insufferable in ways that must have seemed cool to us back then. It canonised the pairing of Kajol and Shah Rukh Khan, launched Rani Mukerjis career and became, for a spell, the third-highest-grossing Indian film ever. Like everyone else in the country, I watched it in the theatre when it released, and again when it played on TV. I cant sit through 10 minutes of it now, let alone the whole three hours. I suspect its the same with a lot of people my age.

Several other big releases of 1998 were romantic dramas too. Three films that year had pyaar (love) in the title: Pyaar To Hona Hi Tha, Pyaar Kiya To Darna Kya and Jab Pyaar Kisise Hota Hai. There was also Mani Ratnams haunting Dil Se (From the Heart) and Feroz Khans Prem Aggan (Burning Love), one of the daftest Hindi films ever. Bobby Deol had a hit with the action film Soldier, as did Amitabh Bachchan and Govinda with the slapstick Bade Miyan Chote Miyan and Aamir Khan with the On the Waterfront remake Ghulam. Dil Se is the only one of this lot worth revisiting, though at the time it eluded both critics and viewers. The biggest surprise was a no-budget indie called Hyderabad Blues, made by a former engineer named Nagesh Kukunoor for 17 lakh rupees (a million is 10 lakhs; a crore is 100 lakhs) in two-and-a-half weeks. It was mumblecore before the term existed, and one of the first proto-Hindies after the Arundhati Roy-scripted In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1989).

Change was afoot, even if it seemed like cinema was in a rut. This was the year Hindi film was deemed an industry by the government. This meant that makers could apply for loans from financial institutions instead of trying to secure them from builders and jewellers, many of whom used movie productions to offload their black money. Film editing was poised to go digital songs and promos were being cut on Avid, and the trusty Steenbeck machines would soon be put out to pasture. DVDs were trickling into the market, first as luxury items, then as cheap knockoffs in seedy shops. PVR opened Indias first multiplex in Delhis Saket neighbourhood in 1997. With all the nostalgia associated with single-screen theatres today, it's easy to forget how we welcomed multiplexes when they started out. Their pricing was, and still is, prohibitively expensive for the urban poor, but they dramatically improved viewing conditions for those who could afford them. For my generation, old enough to have grown up watching movies in single-screens but not so old as to have a sentimental attachment to them, it was a gleaming new world.

As PVR expanded and competitors entered the market, multiplexes started to have an impact not just on how we were seeing movies but on the kinds of movies that were being made. Multiple screens meant less pressure to carry a single saleable film. You could run something like Hyderabad Blues one show a day for a week, while also screening whatever mainstream commercial product was in circulation then. For a brief period, these smaller, bolder releases were referred to as multiplex films.

After making his first original Hindi film, Rangeela (1995), with Aamir Khan, and his second, Daud (1997), with Sanjay Dutt, Varma wrong-footed everyone by hiring a bunch of nobodies for his next project. Satyas credits read like an honour roll today. In 1997, an average moviegoer would have been hard-pressed to recognise more than three names. There was Anurag Kashyap, in his mid-twenties, all restless energy and no screen credit to show for it. Saurabh Shukla, with two acclaimed, little-seen films under his belt in a two-film-old career. Manoj Bajpayee, going stir-crazy after months of bit parts and TV work, hungry for a chance to explode onscreen. Vishal Bhardwaj, building a reputation as a composer, nursing a dream of directing one day. Makarand Deshpande and Apurva Asrani, Sandeep Chowta and Aditya Srivastava, all standing around on the ground floor, waiting for the elevator.

Its perfect, this moment. Satya, before it was a film, before the accolades, a cloud of possibility and potential. Everyone at the start of their careers, drinking cheap alcohol in one-room apartments, complaining, plotting their takeover of Bollywood.

The film opened on 3 July 1998. For the first day or two, collections werent encouraging. The newcomers gulped. Varma, too, must have wondered if he was headed for his second failure in a row after Daud. Hed already moved on to Kaun, following the ancient showbiz maxim which says you book your next gig before a release, not after. Would he be able to continue making Hindi films if Satya wasnt successful, or would this mean a return to Telugu cinema?

To everyones relief, business started picking up. People read the reviews over the weekend, went to watch it, came back and raved to their friends. Word got around that an unusually gritty Hindi film was in theatres. I remember a friends mother recommending it to my parents, with the caveat that it might not be suitable for our 14-year-old sensibilities (it wasnt, but we watched it anyway). Shobha De wrote about it, which meant the film had become small talk in fancy Mumbai parties. The actors started getting recognised on the street. It wasnt a huge hit, but it ran steadily for a couple of months, celebrating a silver jubilee in Mumbai. More importantly, at a time when Hindi cinema was spinning its wheels, it showed the way forward.

Next page