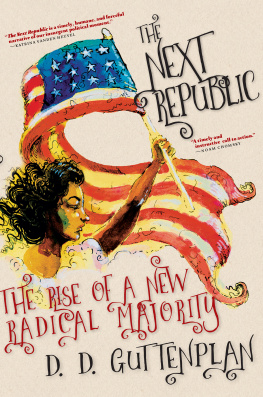

ALSO BY D. D. GUTTENPLAN

The Holocaust on Trial

AMERICAN

RADICAL

The Life and Times of

I. F. STONE

D. D. Guttenplan

Farrar, Straus and Giroux New York

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2009 by D. D. Guttenplan

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2009

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to quote from the following:

September 1, 1939 by W. H. Auden, copyright 1940 by W. H. Auden, renewed by the Estate of W. H. Auden. Used by permission.

Isaiah Berlin, unpublished correspondence with I. F. Stone. Reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust. Copyright the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust, 1975.

Michael Blankfort, unpublished correspondence with I. F. Stone. Used by permission of Mrs. Michael Blankfort and the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

St. Bartholomews Eve by Malcolm Cowley, copyright the Literary Estate of Malcom Cowley. Used by permission of Robert W. Cowley. Malcom Cowleys unpublished correspondence with Isidore Feinstein is used by permission of the Newberry Library, Chicago.

Boats in a Fog copyright 1925, renewed 1953 by Robinson Jeffers, Woodrow Wilson, Shine, Perishing Republic copyright 1934 by Robinson Jeffers, renewed 1962 by Donnan Jeffers and Garth Jeffers, from Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers by Robinson Jeffers, copyright 1925, 1929, renewed 1953, 1957 by Robinson Jeffers. Used by permission of Random House, Inc.

Freda Kirchwey, unpublished correspondence with I. F. Stone. Used by permission of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University.

Robert Silvers, unpublished correspondence with Isaiah Berlin. Used by permission.

I. F. Stones unpublished correspondence, copyright the Estate of I. F. Stone. Used by permission of Celia Gilbert, Christopher Stone, and Jeremy Stone.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Guttenplan, D. D.

American radical : the life and times of I. F. Stone / D. D. Guttenplan.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-374-18393-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-374-18393-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Stone, I. F. (Isidor Feinstein), 19071989. 2. JournalistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title

PN4874.S69 G88 2009

070.92dc22

[B]

2009009667

Designed by Jonathan D. Lippincott

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Alexander, who was there at the beginning

and for Zoe and Theo,

who arrived in medias res:

Like the poets Ithaka,

you three have made these years

a beautiful journey

And finally, in memory of

Andy Kopkind,

whose voice is always in my ear

CONTENTS

PREFACE

To the Meet the Press audience on December 12, 1949, there was nothing special about the confrontation between I. F. Stone and Dr. Morris Fishbein. As editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Fishbein was a well-known foe of what the AMA called socialized medicine in any form; Stone, a sometime member of the Meet the Press panel since 1946, could always be relied on for provocative, irreverent, and persistent questioning. The countrys most influential physician had already denounced national health insurance as the kind of regimentation that led to totalitarianism in Germany. When Fishbein also condemned compulsory coverage as socialistic, Stone demonstrated why the shows producers considered him a good needler: Dr. Fishbein, lets get nice and rough. In view of his advocacy of compulsory health insurance, do you regard Mr. Harry Truman as a card-bearing Communist, or just a deluded fellow traveler?

The arguments over national health care did not advance much in the next sixty years, but for I. F. Stone that broadcast marked a kind of limit. After a career that saw him rise to national prominence not only on television and radio but as a correspondent for the Nation and a columnist for PMthe legendary New York tabloid that refused advertisements and revolutionized American newspapershe was about to disappear. Not literally, of course. For the moment, Stone still had a job, though his latest employer, New Yorks Daily Compass, had fewer readers than the same citys Yiddish Daily Forward. And if the days when his habit of sauntering into various New Deal agencies and making free with the phoneand the fileswere behind him, he still had friends in Washington, some of whom were even willing to be seen talking with him. But it was to be another eighteen years before I. F. Stone was next on national television. And though he lived to an age when political punditry dominated Sunday morning broadcasting, he was never again invited back on Meet the Press.A decade earlier, Stone had already developed as much access as any journalist in the country; his patrons included Felix Frankfurter, the Harvard Law professor and future Supreme Court justice, and Thomas Tommy the Cork Corcoran, the presidents political fixer. During World War II, Stone worked closely with Walter Reuther and other union leaders in proposing plans to increase production of aircraft and arms; his exposs of the Alcoa Aluminum trusts war profiteering and the Standard Oil Companys cozy cartel agreements with the German firm I. G. Farben brought him kudos from the chair of the special Senate Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, Harry S. Truman. After the war, Stones undercover journey accompanying Jewish survivors of the Nazi Holocaust as they defied the British blockade of Palestine made frontpage headlines; his reports under fire from the new state of Israel made him a hero to Americas Jews.

And then, slowly, he vanishes. He opposes President Trumans loyalty program and the establishment of NATO, supports the Marshall Plan, and is denounced by the Communist Daily Worker for reporting favorably from Yugoslavia, whose leader, the former partisan fighter Josip Tito, declares his countrys independence from the policies imposed in the Balkans by the Soviet Union. In February 1950, speaking at a rally against the hydrogen bomb, Stone begins, FBI agents and fellow subversives The bureau will soon put him under daily surveillance. Although he is the author of four books, each one more successful than the last, when he writes another, on the Korean War, no publisher in America will touch it. Returning to New York in 1951 after a year in Paris as foreign correspondent for the Compass, he cant get his passport renewed. By the time that paper closes its doors in 1952, he is effectively blacklisted as a reporter; not even the Nation will give him a job. He is forty-four years old and relies on a hearing aid to make out any sound below a shout. He writes, I feel for the moment like a ghost.

For some time he lives in a kind of internal exile. The American reporter more closely identified with the Jewish state than any other sits in Washington, D.C., in a rented office waiting for the phone to ring. When, after three years, he realizes that he hasnt had a single visitor apart from building maintenance workers and the mailman (who has been secretly sharing Stones mail with the FBI), he gives up the office and works from home. Starting with a tiny fragment of his old magazine and newspaper audiencetoo few at first even to cover expenses, let alone pay his salaryhe decides to launch his own newspaper.