www.headofzeus.com

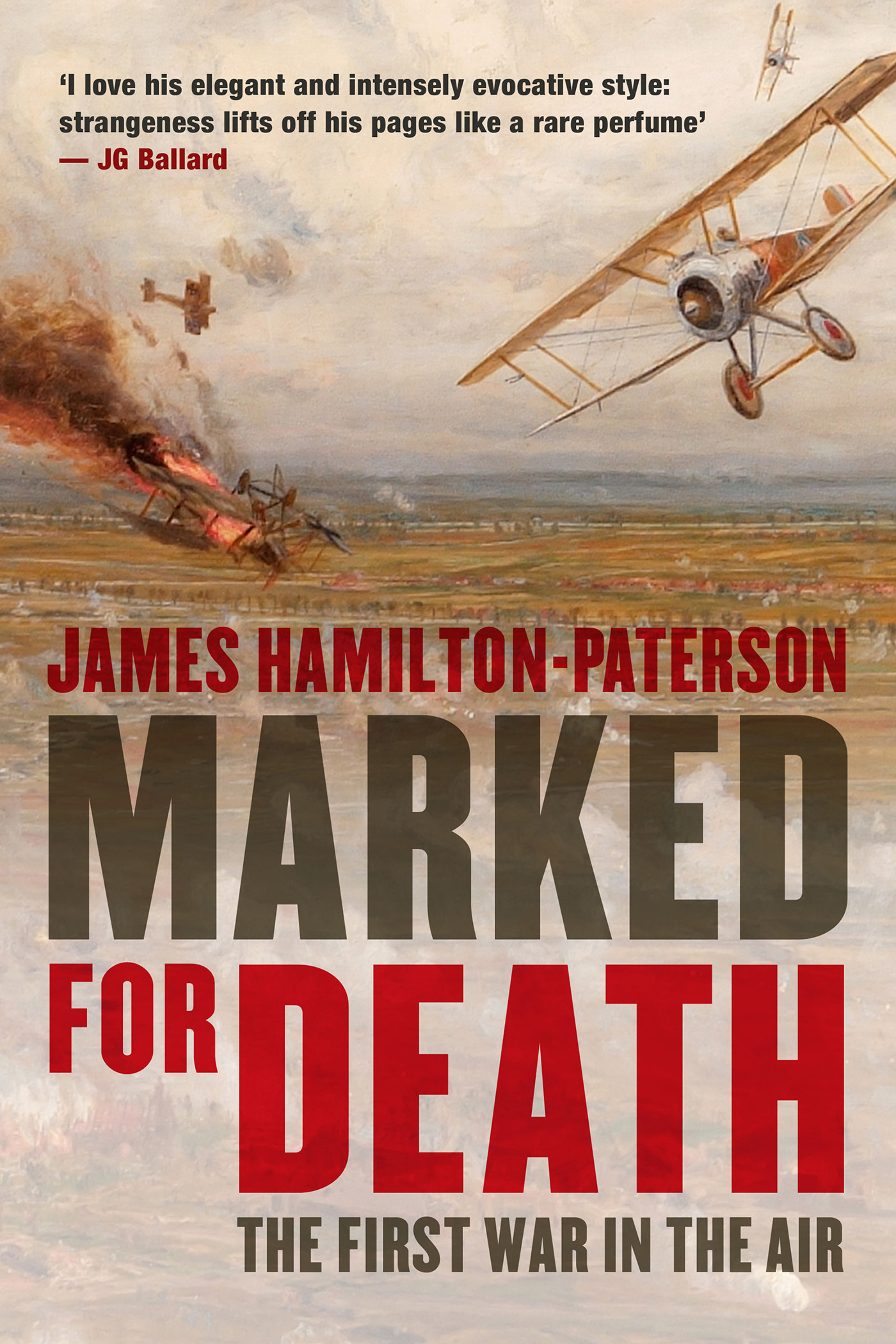

Every man who went aloft was marked for death, sooner or later, once his wheels had left the ground.

Anthony Fokker

Contents

To Chris Royle, with grateful thanks

Scarcely ten years after powered aircraft had first left the ground they were pressed into service in the First World War, which consequently also became the worlds first-ever air war. Seen from a purely military point of view, aviation in that vast conflict was little more than a highly visible sideshow. Historians generally agree that it had limited influence on the wars outcome, even though by the end it was clearly going to change the nature of warfare and ensure its own future. Air power developed to have a decisive strategic function in the Second World War and thereafter was destined to reign supreme down to the present day, when air dominance above a conflict is considered essential.

Out of the 65 million men mobilised between 1914 and 1918 by the Allies and the Central Powers combined, it is now generally estimated that some 9 million were killed outright and 21 million wounded. Even allowing for the first-ever air wars restricted dimensions, the toll it took of flying men was minuscule compared to that of the trenches. Nearly lost in the overall statistics are the 6,994 British and Empire aircrew who were casualties on the Western Front between 1914 and 1918 a figure that includes those killed, wounded, or missing in action. Flying was an extremely hazardous affair in the First World War.

The grip aviation held on the publics imagination at the time was remarkable. This was partly because flying itself was still a novelty and widely seen as daring and glamorous, and partly because most people understood and still understand so little about it and how it was used in the war. Newspaper coverage at the time did much to promote this ignorance by tending to concentrate on the air aces, whereby a handful of particularly successful combat pilots were singled out for propaganda purposes to become bemedalled national heroes. This system was clearly an instinctive response to the wholesale slaughter of the infantry battles. It promoted publicly visible examples of individual heroism, gallantry and self-sacrifice. But it also promoted a myth that has endured to the present day. The impression took hold that pilots in the air above the trenches were conducting a throwback to a cleaner sort of war: gladiatorial, personal, even romantic. This careful skewing of reality has made it easy for later generations to retain a very limited and trivialised version of the first war in the air and, indeed, to misunderstand its significance ever since.

The example of Manfred von Richthofen, the wars top-scoring fighter ace (with a tally of eighty victims of whom fifty-four were downed in flames), offers a case in point. Until the last months before the Armistice no airman other than observation balloon crews wore a parachute in the First World War, and fire was the chief nightmare that haunted them awake and asleep. During his pre-eminence Richthofen became known as The Red Baron partly because he actually was a baron and partly from his later affectation of flying an all-red aircraft. In recent decades this nickname has been appropriated for films, a pizza chain and a motorbike franchise, as well as for arcade and video games (one internet advertisement reads Fly your biplane in air battles of the First World War and defeat the Red Baron!). The jokey title of Britains early seventies TV comedy series Monty Pythons Flying Circus was also a direct reference to the nickname given to the Jasta formations in which Richthofen flew. Probably the most extreme example of this stone-cold killer being tamed into a cuddly fantasy is afforded by the comic-strip dog Snoopy, who now and then sits atop his kennel pretending to fight the Red Baron, wearing a leather flying helmet and goggles with a scarf blowing behind him in an imaginary slipstream. There are even stuffed toys of Snoopy in this guise. This is surely one of the strangest trajectories in all contemporary myth, stretching as it does directly from a modern childs bedroom back to a war in which many a nineteen-year-old victim of Richthofen, his flying gear soaked in petrol, fell wrapped in flame from 8,000 feet, trailing smoke and screaming for the thirty-odd seconds it took him to hit the ground. Richthofen once observed: When I have shot down an Englishman my passion for the hunt is satisfied for fifteen minutes.

A similar conversion of the horror and agony of aerial warfare into near-jocularity can be followed in what happened in Britain to the fictional character of Biggles or Major James Bigglesworth, RFC, the creation of W. E. Johns. Having served in the trenches on two fronts, Gallipoli and Salonika, Johns retrained as a pilot with the Royal Flying Corps and by 1918 was in France flying two-seater Airco (de Havilland) 4 bombers with 55 Squadron out of Azelot, near Nancy. In D.H.4s the main fuel tank was between the two cockpits and very likely to be hit by an attacker aiming for either the pilot or the observer. On 16th September 2nd Lieutenant Johns and his observer, 2nd Lieutenant A. E. Amey, were shot down over the German lines. By some miracle the machine did not catch fire even though, as Johns described it later, it was trailing a grey plume of petrol vapour and my cockpit was swimming in the stuff. was to be executed: his aircraft had been mis-identified as one that had bombed a village Sunday School some days earlier, killing many children. He was saved from death only by the timely intervention of the pilots who had shot him down and he was harshly interned for the remaining months of the war.

In early 1932 Johns became the editor of a new monthly magazine, Popular Flying . For its April edition he published his first story featuring the fictional Biggles in order to tell British readers what war flying was really like, drawing on his own experiences in the Army, the RFC and the RAF. He did this partly to offset the absurdly US-centric accounts of the air war in imported American pulp magazines, and partly as a corrective to what he saw as Europes gradual slide towards another war facilitated by mythologised memories of the previous one. Johnss hard-hitting editorials warning the government of Britains unpreparedness for air war and Nazi Germanys ever-expanding Luftwaffe were eagerly and widely read, although little welcomed in Whitehall.

From the start Popular Flying was a great success and Johns wrote sundry more stories about Biggles that became a feature in themselves. Almost from the first they attracted the attention of a childrens editor who spotted Biggless potential as a pilot hero of boys adventure fiction, and Johns duly became a childrens author even as he went on writing editorials and technical articles about aviation for his magazine. Given the period, Johnss hero was remarkably un-jingoistic. Biggles consistently condemned war, was often cynical about authority and officialdom, and was not chauvinistic about the enemy pilots he flew against unless they had first earned his moral condemnation. This was probably a fair rendering of attitudes that prevailed among airmen, who by 1918 were frequently nihilistic and sometimes downright mutinous. One early story for Popular Flying had Biggles suffering from burnout and combat fatigue, often close to tears and hitting the whisky bottle before flying on early morning patrols. The description fits exactly with many non-fiction accounts (including those by squadron medical officers), and the spectacle would have been all too familiar to Johns and his contemporaries in a front-line squadron. When the story was republished in book form the publisher wanted the whisky removed. Heroes in boys stories were not allowed to have a drink problem, no matter how shattered their nerves. Johns refused, although he did judiciously suppress some of the other details of life on the front such as airmens swearing, whoring and gruesome injuries. Even so, this is hardly a description of a conventional storybook role model: