Contents

ALSO BY JOHN HEMINWAY

The Imminent Rains: A Visit Among the Last Pioneers of Africa

No Mans Land: A Personal Journey into Africa

African Journeys: A Personal Guidebook

Disney Magic: The Launching of a Dream

Yonder: A Place in Montana

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2018 by John Heminway

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

New Directions Publishing Corp. and David Higham Associates Limited: Excerpt of Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night by Dylan Thomas from The Poems of Dylan Thomas, copyright 1952 by Dylan Thomas. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. and David Higham Associates Limited.

Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC: Excerpt of Guilty written by Gus Kahn, Harry Akst, and Richard Whiting. Copyright 1931 by EMI Feist Catalog Inc. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219. All rights reserved. Reprinted by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Heminway, John Hylan, 1944author.

Title: In full flight : a story of Africa and atonement / by John Heminway.

Description: New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017021058 | ISBN 9781524732974 (hardcover) R 692 | ISBN 9781524732981 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Spoerry, Anne, 19181999. | Women physiciansAfricaBiography. | Aeronautics in medicineAfrica. | Humanitarian assistanceAfrica. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women. | TRAVEL / Africa / General. | HISTORY / Holocaust.

Classification: LCC R 507. S 64 H 46 2018 | DDC 610.92 [ B ] DC 23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017021058

Ebook ISBN9781524732981

Cover design by Janet Hansen

v5.1

a

For Kathryn and Lucia

Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings. An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest. The air was warm, thick, heavy, sluggish. There was no joy in the brilliance of sunshine. The long stretches of the waterway ran on, deserted, into the gloom of overshadowed distances. On silvery sandbanks hippos and alligators sunned themselves side by side. The broadening waters flowed through a mob of wooded islands; you lost your way on that river as you would in a desert, and butted all day long against shoals, trying to find the channel, till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off forever from everything you had known oncesomewherefar away in another existence perhaps. There were moments when ones past came back to one, as it will sometimes when you have not a moment to spare to yourself; but it came in the shape of an unrestful and noisy dream, remembered with wonder amongst the overwhelming realities of this strange world of plants, and water, and silence. And this stillness of life did not in the least resemble a peace. It was the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention. It looked at you with a vengeful aspect.

JOSEPH CONRAD, HEART OF DARKNESS

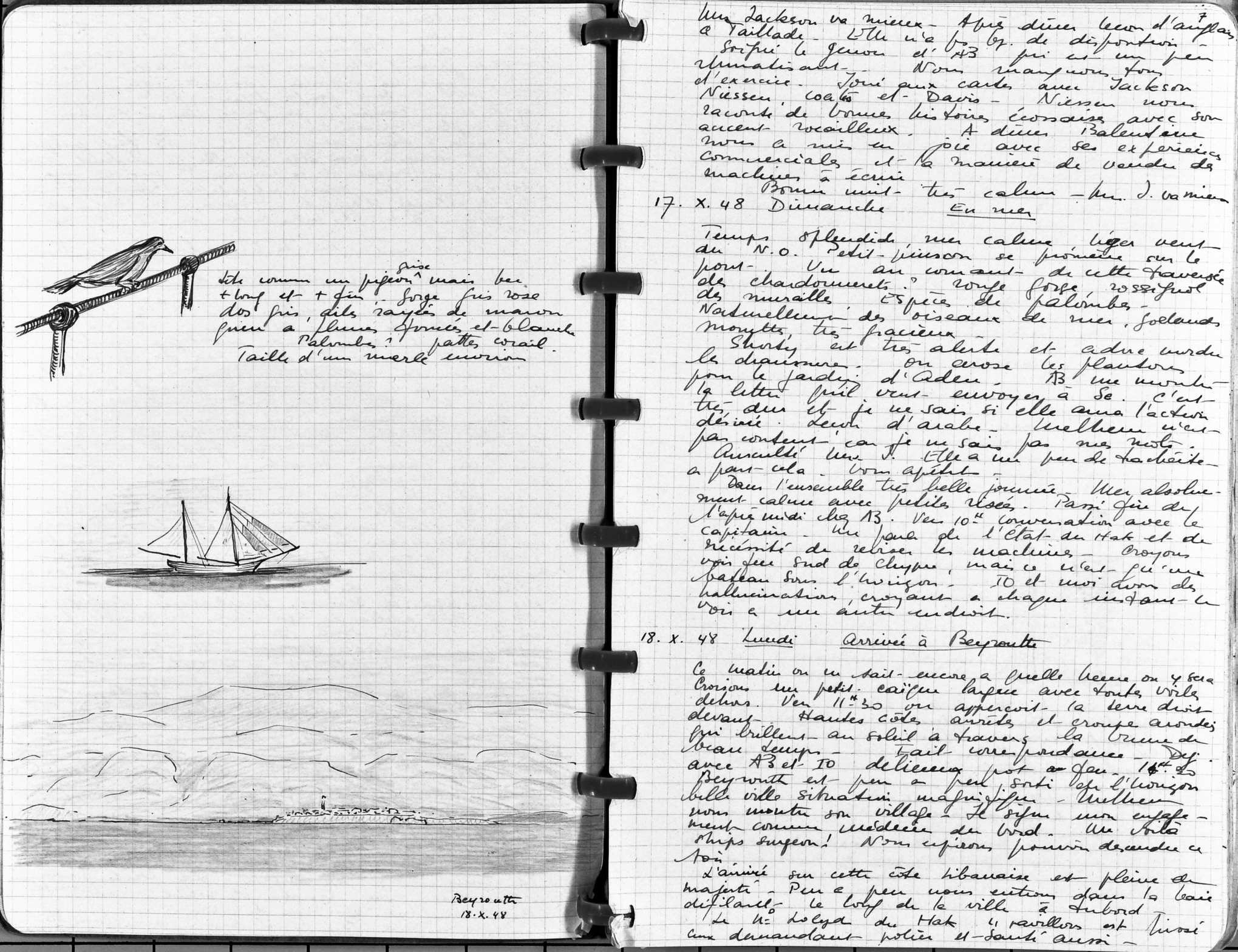

Annes 1948 journal: One week after escaping from France as she prepares to land in Beirut.

PROLOGUE

THE END

THE ENDOn February 6, 1999, a mob of yellow-billed kites circled Wilson Airport in Kenya, the busiest civil aviation hub in all Africa. The carrion birds had just left the nearby Nairobi slum of Kibera and were exploiting an uncommon void in the airspace over the runways. They might have been honor guards as they circled above a cortege of Land Cruisers, sedans, and buses out of which poured mourners: women in dated frocks and men stiff in regimental blazers, shiny at the elbow from age. Here and there, Ismaili and Sikh women, exiting minivans, arranged their saris. The great majority of arrivals were African, dressed in clothes reserved for church, weddings, and death.

Within the hangar only a few found seats; otherwise, it was standing room only. None could recall Wilson Airport so hushed, with all airplanes tied down, as a mark of respect.

East Africa was in mourning for its celebrated flying doctor Anne Spoerry (pronounced Shpeuri), felled by a stroke four days previously at age eighty, still in harness to her lifes calling, helping the rural poor. Over a thousand people found space in the Flying Doctors hangar to pay last respects. The ceremony rang with the solemnity of a state funeral. Many had traveled from overseas, and no sector of Kenyan society was lacking. Infants strapped to their mothers backs, creaky-limbed elders, a colorful array of tribes, Asian merchants, Europeans, Americans, government ministers, the diplomatic corps, and unattended children all jostled for sight lines in the echoing metal building.

Dr. Anne Spoerry had spent nearly fifty years in Africa, tending to the health of over a million patients, drawn mostly from the far corners of Kenya. It was said no other physician could match her industry, tenacity, and productivity in the cause of Africas well-being. As a sole lifeline for the poor, it was not uncommon for patients to declare her a saint.

In the hangar the mourners were a study in devotion, stifling coughs, eyes flickering from emotion, minds reliving the triumphs of her life. The sight of Spoerrys Piper Lance PA-32 plane, known throughout Kenya as Zulu Tango from its call sign, 5Y-AZT, drew many to reach for handkerchiefs. Positioned front and center, both coffin and airplane were draped in tropical garlands. For those who once awaited Anne on ribbon-thin airstrips, this Africa-scarred machine spoke of endurance and courage. Zulu Tango had been their sole glimmer of hope in a land begging for miracles.

Over the course of Spoerrys long career, no place had been too far, no airstrip too risky, no patient beyond caring. Inside the echoing hangar, eulogies ran long, with every speaker heaping praise on the doctor for her no-nonsense style, strength, and compassion. An elderly woman whose broken arm Dr. Spoerry had set years before likened her to Mother Teresa. Another called her an angel from heaven. Wherever she landed, she was greeted as Mama Daktari, Mother Doctora sobriquet that met with Annes hearty approval. When an unscheduled speaker, footsore from travel, rushed the podium, mourners checked their programs to see if they had missed something. He was a tall, dignified farmer, dressed in his one suit, confected with the red dust of Africa, and a tie that was black and borrowed. All leaned forward to hear his love sonnet. In linen-soft words, he declared that Dr. Spoerry had saved not just him but entire villages. He was here at the urging of his community to reassure all Dr. Spoerry would never be forgottennot in the far corners of Africa, in this generation or the next. When he finished with a barely audible God bless you, Mama Daktari, the Kenya Boys Choir burst into Ave Maria. Soon the chanting bridged into a song of old Africa with one lone alto, repeating

THE END

THE END