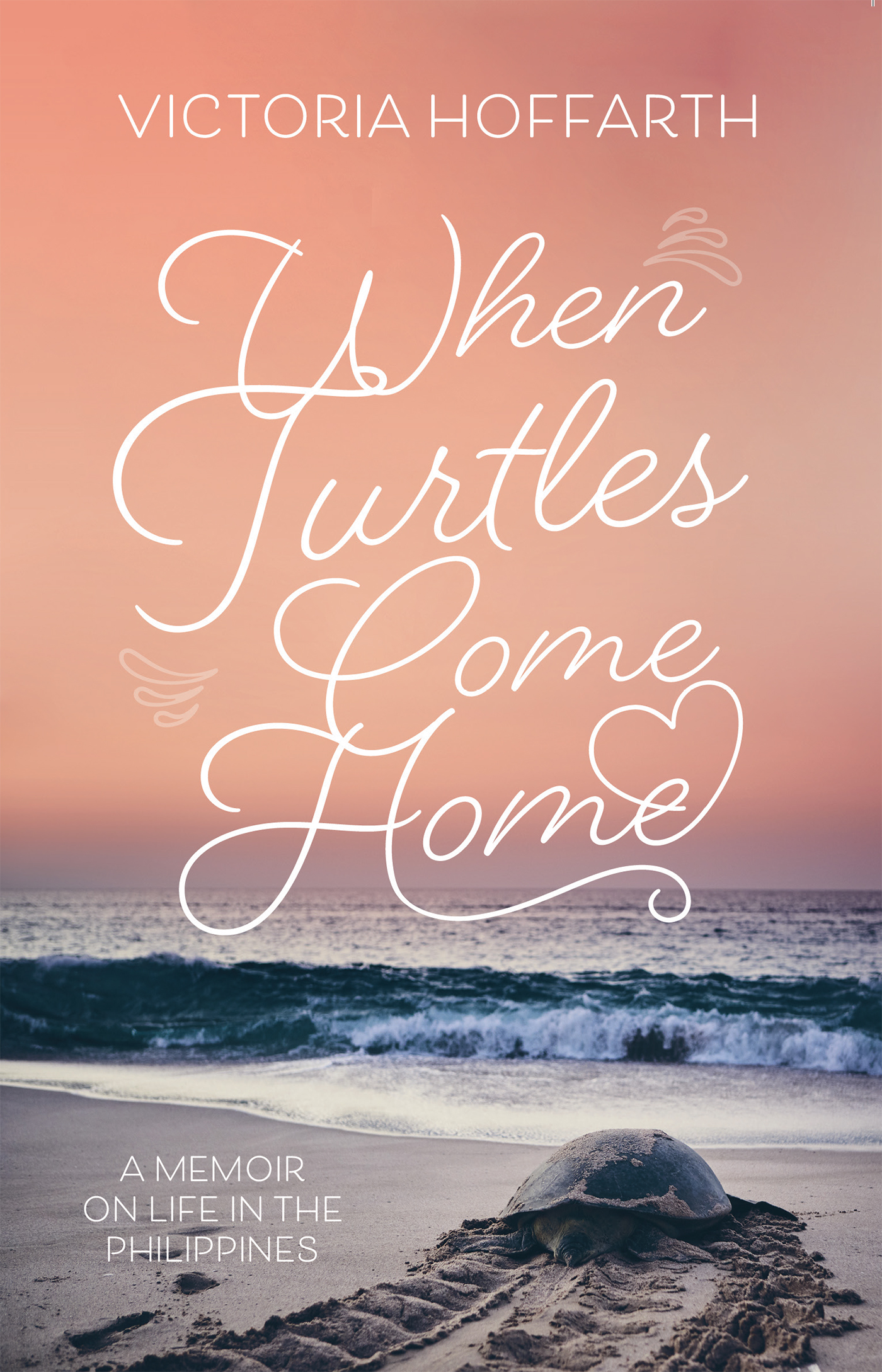

Copyright 2019 Victoria Hoffarth

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1838599 034

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

To my father who crafted me a pair of wings

and taught me how to fly

To my mother who showed me how to leap with

both feet tied firmly on the ground

To Klaus who provided me with the tools

To Paul who has borne the consequences

Turtles carry their homes on their backs, travelling thousands of miles each year. But eventually, guided by the magnetic fields of the earth, they are programmed to return to the place of their birth.

Contents

Preface

My interest in writing started when I was quite young. At that time, I thought I could write about my personal experiences. Those were what I knew, after all. I remember asking for advice from my teacher and was told, How could you write a memoir? What will you write about? Who would be interested in ordinary lives such as ours? Only people who have been in the public eye or who have had unusual experiences write memoirs. In fact, this truism was repeated only recently by a literary agent who gave me his opinion when I mentioned that I was writing my memoir. He advised me to put my draft inside the drawer and go write a novel.

Nonetheless, when I went to a major bookstore in London to ask if they had any how-tos on memoir writing, the salesman commented, Memoirs are so self-indulgent... and, in a back-handed insult to women, every housewife wants to write her memoir. I now understand what he meant as I have indulged myself in a couple of anecdotes that I had decided did not exactly fit my narrative framework, yet which, I sincerely hope, will be of interest to the readers. I am assuming that, in a memoir, this would be permissible.

From those who considered writing memoirs absolutely fine, came various dictums: you have to arouse the readers curiosity. Your opening lines are some of the most important in your book so be very careful about them. They should make your reader want to keep on reading. I was instructed about craftsmanship and structurechronological sequencing is so boring, think about flashbacks and flash-forwards. Build up your story with unforgettable settings and interesting characters, and most important of all: show, dont tellno expositories please, only stories!

As a consequence, all these comments froze me in my tracks, and for years I kept toying with the idea but never really made a serious attempt at starting. How could you sit down and compose your first lines knowing they would be some of the most important in your book? It didnt heIp that I was also busy with my family and career. However, I continued to keep notes, attend writing classes and writers events, including the Hay-on-Wye writers festival in Wales, UK where authors spoke about their own experiences. I have to admit, I felt totally discouraged. How do you respond to someone who says, I cant help but write. All these years I couldnt help but NOT write!

At one of these events, I had a brief encounter with the writer John Forsythe. I asked him how he started. Dump all those writing classes, he said bluntly. When he was a teenager, he decided he wanted to write. So he just sat down and wrote. He started copying and imitating the manner in which his favourite authors expressed themselves, and only developed his own personal style much later.

Teenager indeed! I was by then decades older than a teenager, and no longer had the time to develop my craft. How about the folk artist Grandma Moses, I reminded myself. She only started painting when she was seventy-eight! Battles raged in my mind. Instead of a memoir, how about writing a personal narrative or a personal essay, I asked myself. They sounded less ambitious and perhaps more acceptable for nobodies like me. In short, I was stuck!

Then, I happened to chat with a lawyer-friend who told me he was just finishing writing his memoir. This, he said, would be the legacy he wanted to leave his children. I told myself Why not? Why did I have to write for publication? Why not leave something behind in the attic, perhaps never to be read. But then again, possibly, in the future my reflections might be of use to someone? It would be a means of addressing my thoughts on friends and family, my community, country, indeed the whole state of the world! Why not leave something for my son Paul? Most people, Filipinos included, think of inheritance in terms of material wealth. But there is an even more important legacy: the wealth of documentation about a world gone by. I realised I wanted to leave Paul and his children descriptions of events that might give them some awareness of how their lives can be influenced by the context of the past. I wanted to pass on the wisdom I had accumulated over the years, not just through the narration of my life story, but more importantly, by including my observations of the world around me and how my evaluations of these environmental forces have shaped the philosophies by which I live.

My legacy should be there for the taking. I hope that, in the event that a member of some future generation glances at it, they could have just a bit of an idea of what my world was likeway back in the 1950s in Negros and in Manila in the 1960s; in New York of the 1970s; then trying to make my way back to the Philippines in the1980s, working hard but not quite working smart at the business school where I taught. London came in the 1990s, spending some time in Germany; and back to Manila again in 2004, trying to fit in: the proverbial square peg in a round hole.

In a sense, this book is also therapy for me as the process is just as important. I once read a novel called Zenos Conscience . Zeno started by wanting to give up smoking. He was asked by his psychoanalyst to write down his lifes story as a form of therapy, in order to make sense of his own history. I believe I have a bit of that motivation as well. As a true introvert in the Jungian sense of the word, I live inside my head. Thoughts jumble and tumble, inside and out, up and down. Experiences of years ago can suddenly resurface in early morning flashes andEureka!I realise what they mean to me! The process of writing this memoir has given me the opportunity to explore them.

Now that I am over seventy, this is as good a time as any to make sense out of my life, to carefully draw its contours, so to speak, before it is finally done. These contours have been quite uneven, sometimes very thin and narrow as I withdrew into myself; other times lined with bold strokes of productivity and growth; or fat and pregnant, breaching its confines as I reached out to others. One day, l will leave it to the stars to finally paint the shape of my life: a speck of dust in the vast universe of time.