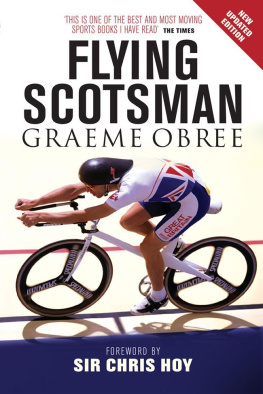

Flying

SCOTSMAN

Graeme Obree

Flying

SCOTSMAN

Foreword by

Sir Chris Hoy

This edition published in 2010 by

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2003 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright Graeme Obree, 2003

Foreword Copyright Chris Hoy, 2010

Permission has been sought for the use of extracts from LEquipe

The moral right of Graeme Obree to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means,

electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the express written permission of the publisher

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-106-4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record is available on request from the British Library

To

My wife Anne, all my family who have supported me, and, equally, to all those volunteers who selflessly give their time and without whom amateur sport would not exist.

foreword

Geniusnoun 1. an exceptionally intelligent person or one with exceptional skill in a particular area of activity.

Some might say that the word genius is used far too often these days, diluting its real meaning and therefore its impact. But when it is applied in reference to Graeme Obree, you can be sure it hasnt been chosen hastily.

Graeme is a genius in the true sense of the word. His uncanny ability to tackle problems from an angle that no one else could have thought of makes him a one-off. An original. He sees the world in a different way to us mere mortals and comes up with ideas and solutions which make you laugh, shake your head and say, Why didnt I think of that?!

Unfortunately, as history has so frequently shown us, with genius often comes torment. In this book, Graeme very openly discusses his life and the struggles he has faced and continues to face every day. This only serves to endear him further to those who have followed his career, to realise that in spite of his demons and without huge financial backing, he has managed to change the face of his sport and bring joy to countless fans around the globe.

Graeme has been an inspiration and a hero to me since I first became interested in track cycling, and his sheer determination and commitment have left a lasting impression; it became the model to which I aspired to emulate. Although we rode in entirely different disciplines, his message was universal; give 100 per cent every time you sling your leg over the crossbar, whether it be a cold winter training session or the final of the Olympic Games. We were room mates at the 1997 World Championships, and it was there that I first got to know Graeme and hear some of the stories that are in the following pages. I remember thinking at the time that it would make an incredible book, and so I was delighted when I heard that he was going to put pen to paper and get it published.

His story is one which has been told and re-told on countless club runs over the years and has already been passed onto a new generation of young cyclists who were too young to see his historic performances. This is the story straight from the horses mouth and one which cant fail to move and inspire.

Chris Hoy

August 2010

one: my early years

My childhood is far more influential in my present than a childhood ought to be, so that is where my story begins.

I was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire on September 11, 1965 and came to Scotland shortly afterwards. My parents, John and Marcie, came from Scotland Ayrshire to be more accurate and were in Warwickshire because of my fathers posting as a police officer. I was their second son and there were only 15 months between Gordon and me.

My fathers posting in Scotland was in Prestwick, Ayrshire and it is there that I have my earliest memories. We moved from Prestwick to Kilmarnock when I was four years old. It was there that I first felt different from the other children we were police. I cannot remember very much because I was so young, but our bogie was set on fire and our tortoise got the chop too.

I have clear memories of Kilmarnock in incidents. My first introduction to the school system was in the form of punishment for a window broken by a stone which left my brothers hand. It was not a deliberate act but an accident in the playground, which was just by our house. It annoyed me that the punishment could not be joint and my first impression of school was, for me, the correct one, as time would prove.

I also quite vividly remember the day my brother and I learned to ride our bikes at the same moment. It was Uncle Stuart who pushed us off at the top of the brae, side-by-side, with the prophetic words Mind the corner at the bottom! It was white-knuckle stuff and we might have been scuffed a bit, but from that moment on we could ride.

We were not there long before we moved to Newmilns, which was a small town set in a valley, but there the story was no different. Newmilns was parochial enough to single you out, but large enough to be nasty with it, to compound matters we were not only police, we were also newcomers.

It was a terrible combination and from day one at school we were the filth. Part of the problem was the fact that my fathers posting was in the valley itself, so the enmity towards him was passed down to the local children from their parents and from them to us. We were outsiders the entire time we were there, which was eleven years.

The enmity towards us manifested itself in three ways name calling, ostracism and violence. Even my sister Yvonne, five years my junior, was not excluded from the party but the violence was mainly reserved for Gordon and me. It seemed that rarely a week would go by without my being strapped for fights I never asked to be in. In fact I was doing my utmost to avoid them, but seeing as I was a common denominator, I was seen as a troublemaker by Mr Gillespie, the headmaster.

This set the pattern for my whole school life and clowning around became habitual as a means of trying to be accepted. When I think back on my school days I can only remember feeling sadness and loneliness. The violence does not stand out so much, although there was plenty of it and some of it quite extreme. Being head-butted from the crowd or roughed up was common enough to lose its shock factor and, apart from the worst incidents, I do not think that the violence itself left a large impression on me emotionally.

Avoiding violence, and the fear of violence, there were worse forms of victimisation: those that were intangible. When it came to physical violence though, I thought of it and perceived it as two different sensations after a while. Being kicked about the head was so different from being kicked about the body.

Ironic as it may seem, in the midst of it, violence has a beauty and excitement that nothing else can generate. Sometimes, even though it was nothing more than extreme physical harm, I could almost be disappointed when it ended. At times the most extreme violence, especially to the head, brought an orgasm of fear, excitement, panic and adrenaline.

Nonetheless, I always slipped back to my mode of violence avoidance.